1

Introduction

INTRODUCTION

Simply defined for now, an effect size usually quantifies the degree of difference between or among groups or the strength of association between variables such as a group-membership variable and an outcome variable. This chapter introduces the general concept of effect sizes in the contexts of null-hypothesis significance testing (NHST), power analysis, and meta-analysis. The main focus of the rest of this book is on effect sizes for the purpose of analyzing the data from a single piece of research. For this purpose, this chapter discusses some assumptions of effect sizes and of the test statistics to which they often relate.

NULL-HYPOTHESIS SIGNIFICANCE TESTING

Much applied research begins with a research hypothesis that states that there is a relationship between two variables or a difference between two parameters, such as means. (In later chapters, we discuss research involving more than two variables or more than two parameters.) One typical form of the research hypothesis is that there is a nonzero correlation between the two variables in the population. Often one variable is a categorical independent variable involving group membership (a grouping variable), such as male versus female or Treatment a versus Treatment b, and the other variable is a continuous dependent variable, such as blood pressure, or score on an attitude scale or on a test of mental health or achievement.

In the case of a grouping variable, there are two customary forms of research hypothesis. The hypothesis may again be stated correlationally, positing a nonzero correlation between group membership and the dependent variable, as is discussed in Chapter 4. More often in this case of a grouping variable, the research hypothesis posits that there is a difference between means in the two populations. Although a researcher may prefer one approach, some readers of a research report may prefer the other. Therefore, a researcher should consider reporting effect sizes from both approaches.

The usual statistical analysis of the results from the kinds of research at hand involves testing a null hypothesis (H0) that conflicts with the research hypothesis typically either by positing that the correlation between the two variables is zero in the population or by positing that there is no difference between the means of the two populations. (Strictly, a null hypothesis may posit any value for a parameter. When the null-hypothesized value corresponds to no effect, such as no difference between population means or zero correlation in the population, the null hypothesis is sometimes called a nil hypothesis, about which more is discussed later.)

The t statistic is usually used to test the H0 against the research hypothesis regarding a difference between the means of two populations. The significance level (p level) that is attained by a test statistic such as t represents the probability that a result at least as extreme as the obtained result would occur if the H0 were true. It is very important for applied researchers to recognize that this attained p value is not the probability that the H0 is wrong, and it does not indicate how wrong H0 is, the latter goal being a purpose of an effect size. Also, the p value traditionally informs a decision about whether or not to reject H0, but it does not guide a decision about what further inference to make after rejecting a H0.

Observe in Equation 1.1 for t for independent groups that the part of the formula that is usually of greatest interest in applied research that uses a familiar scale for the measure of the dependent variable is the numerator, the difference between means. (This difference is a major component of a common estimator of effect size that is discussed in Chapter 3.) However, Equation 1.1 reveals that whether or not t is large enough to attain statistical significance is not merely a function of how large this numerator is, but depends on how large this numerator is relative to the denominator. Equation 1.1 and the nature of division reveal that for any given difference between means an increase in sample sizes will increase the absolute value of t and, thus, decrease the magnitude of p. Therefore, a statistically significant t may indicate a large difference between means or perhaps a less important small difference that has been elevated to the status of statistical significance because the researcher had the resources to use relatively large samples.

Tips and Pitfalls

The lesson here is that the outcome of a t test, or an outcome using another test statistic, that indicates by, say, p < .05 that one treatment's result is statistically significantly different from another treatment's result, or that the treatment variable is statistically significantly related to the outcome variable, does not sufficiently indicate how much the groups differ or how strongly the variables are related. The degree of difference between groups and the strength of relationship between variables are matters of effect size. Attaining statistical significance depends on effect size, sample sizes, variances, choice of one-tailed or two-tailed testing, the adopted significance level, and the degree to which assumptions are satisfied.

In applied research it is often very important to estimate how much better a statistically significantly better treatment is. It is not enough to know merely that there is supposedly evidence (e.g., p < .05), or supposedly even stronger evidence (e.g., p < .01), that there is some unknown degree of difference in mean performance of the two groups. If the difference between two population means is not 0 it can be anywhere from nearly 0 to far from 0. If two treatments are not equally efficacious, the better of the two can be anywhere from slightly better to very much better than the other.

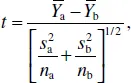

For an example involving the t test, suppose that a researcher were to compare the mean weights of two groups of overweight diabetic people who have undergone random assignment to either weight-reduction program a or b. Often the difference in mean postprogram weights would be tested using the t test of a H0 that posits that there is no difference in mean weights, μa and μb, of populations who undertake program a or b (H0: μa − μb = 0). The independent-groups t statistic in this nil-hypothesis case is

where Ȳ values, s2 values, and ns are sample means, variances, and sizes, respectively. Again, if the value of t is great enough (positive or negative) to place t in the extreme range of values that are improbable to occur if H0 were true, the researcher will reject H0 and conclude that it is plausible that there is a difference between the mean weights in the populations.

Tips and Pitfalls

Consider a possible limitation of the aforementioned interpretation of the statistically significant result. What the researcher has apparently discovered is that there is evidence that the difference between mean weights in the populations is not zero. Such information may be of use, especially if the overall costs of the two treatments are the same, but it would often be more informative to have an estimate of what the amount of difference is (an effect size) than merely learning that there is evidence of what it is not (i.e., not 0).

STATISTICALLY SIGNIFYING AND PRACTICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The phrase “statistically significant” can be misleading because synonyms of “significant” in the English language, but not in the language of statistics, are “important” and “large,” and we have just observed with the t test, and could illustrate with other statistics such as F and χ2, that a statistically significant result may not be a large or important result. “Statistically significant” is best thought of as meaning “statistically signifying.” A statistically significant result is signifying that the result is sufficient, by the researcher's adopted standard of required evidence against H0 (say, adopted significance level α < .05), to justify rejecting H0. There are possible substitutes for the phrase “statistically significant,” such as “result (or difference) not likely attributable to chance,” “difference beyond a reasonable doubt,” “apparently truly (or really or convincingly) different,” and “apparently real difference of as yet unknown magnitude.”

A medical example of a statistically significant result that would not be practically significant in the sense of clinical significance would be a statistically significant lowering of weight or blood pressure that is too small to lower risk of disease importantly. Also, a statistically significant difference between a standard treatment and a placebo is less clinically significant than one of the same magnitude between a standard treatment and a new treatment. A psychotherapeutic example would be a statistically significant lowering of scores on a test of depression that is insufficient to be reflected in the clients' behaviors or self-reports of well-being. Another example would be a statistically significant difference between schoolgirls and schoolboys that is not large enough to justify a change in educational practice (educational insignificance). Thus, a result that attains a researcher's standard for “significance” may not attain a practitioner's standard of significance.

Bloom, Hill, Black, and Lipsey (2008) and Hill, Bloom, Black, and Lipsey (2008) discussed the use of benchmarks that proceed from effect sizes to assess the practical significance of educational interventions. Their approach emphasizes that it is not the mere numerical value of an effect size that is of importance but how such a value compares to important benchmarks in a field. In clinical research, one definition of a practically significant difference is the smallest amount of benefit that a treatment would have to provide to justify all costs, including risks, of the treatment, the benefit being determined by the patient. Matsumoto, Grissom, and Dinnel (2001) reported on the cultural significance of differences between Japan and the United States in terms of effect sizes involving mean differences.

Onwuegbuzie, Levin, and Leech (2003) recommended, where appropriate, that practical significance be conveyed in terms of economic significance. For example, when reporting the results of a successful treatment for improving the reading level of learning-disabled children, in addition to a p level and an estimate of a traditional effect size the researcher should report the estimated annual monetary savings per treated child with respect to reduced cost of special education and other costs of remedial instruction. Another example is a report stating that for every dollar a state spends on education (education being a “treatment” or “intervention”) in a state university, the state's return benefit is eventually Y dollars (Y > 1). Harris (2009) proposed as a measure of educational significance the ratio of an effect size and the monetary cost of the intervention that brings about that effect size. In this proposal, to be considered large such a ratio must be at least as large as the largest such ratio for a competing intervention.

In clinical research the focus is often on the effect size for a treatment that is intended to reduce a risk factor for disease, such as lowering blood pressure or lowering cholesterol levels. However, the relative effect sizes of competing treatments with regard to a risk factor for a disease may not predict the treatments' relative effects on the ultimate outcomes, such as rate of mortality, because of possibly different side effects associated with the competing treatments. This is a matter of net clinical benefit. Similarly, in psychotherapeutic research the focus of estimation of effect size may be on competing treatments to reduce a risk factor such as suicidal thoughts, whereas the ultimate interest should be elsewhere, that is, effect sizes of competing treatments with regard to suicide itself in this case.

More is written about practical significance throughout this book, including the fact that the extent of practical significance is not always reflected by the magnitude of an effect size. The quality of a judgment about the practical significance of a result is enhanced by expertise in the area of research. Although effect size, a broad definition of which is discussed in the next section, is not synonymous with practical significance, knowledge of a result's effect size can inform a subjective judgment about practical significance.

DEFINITION, CHARACTERISTICS, AND USES OF EFFECT SIZES

We assume for now the case of the typical null hypothesis that implies that there is no effect or no relationship between variables; for example, a null hypothesis that states that there is no difference between means of populations or that the correlation between variables in the population is zero. Whereas a test of statistical significance is traditionally used to provide evidence (attained p level) that a null hypothesis is wrong, an effect size (ES) measures the degree to which such a null hypothesis is wrong (if it is wrong). Because of its pervasive use and usefulness, we use the name effect size for all such measures that are discussed in this book. Many effect size measures involve some form of correlation (Chapters 4 and 10) or its square (Chapters 4, 6, 7, 10, and 12), some form of standardized difference between means (Chapters 3, 6, 7, 11, and 12), or the degree of overlap of distributions (Chapter 5), but many measures that will be discussed do...