![]()

Part 1

Economic patterns and the search for explanation

In the first part of this book, we introduce the scope and complexity of our subject, establish the salient patterns in the world’s economic landscapes, and review alternative theoretical approaches to understanding the development of these patterns. Chapter 1 provides the orientation for the book by outlining the relationships between the organization of the world economy and spatial change. In Chapter 2, the major dimensions of the world’s contemporary landscapes are described. We identify dominant and recurring patterns and note the major exceptions to these patterns. Both the patterns and the exceptions raise a number of critical questions about process and theory in economic geography. For example: “How should the development process be conceptualized?,” “What are the processes that initiate and sustain spatial inequalities?,” and “Why are economic activity and prosperity spread so unevenly?” These questions are pursued in Chapter 3, where we outline a broad theoretical framework for under standing the interdependence of the world economy and its spatial components.

Picture credit: Linda McCarthy

![]()

Chapter 1

The changing world economy

Picture credit: Linda McCarthy

The perspective of this book is global. Although local, regional, and national circumstances remain important, what happens in any given locale is increasingly influenced by its role in and relationship to systems of production, trade, and consumption that are global in scope.

In the 1970s, only a few less developed countries (LDCs) had opened their borders to trade and investment. About one-third of the world’s labor force lived in countries with centrally planned economies. Another third lived in countries insulated from international markets by protective trade barriers and currency controls.

Today, more than 7 billion people populate our planet, and most live in countries that have been integrated into global markets. Three population blocs—China, India, and the republics of the former Soviet Union—account for more than 40 percent of the world’s labor force and are important participants in the global market. Many other countries such as the newly industrializing economies (NIEs) of Brazil, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan have also become vital contributors to the world economy.

More than two decades ago, Robert Reich, former U.S. Secretary of Labor, underscored the significance of the rapid pace of globalization:

We are living through a transformation that will rearrange the politics and economics of the coming century. There will be no national products or technologies, no national corporations, no national industries. There will no longer be national economies, at least as we have come to understand that concept. … As almost every factor of production—money, technology, factories, and equipment—moves effortlessly across borders, the very idea of a U.S. economy is becoming meaning less, as are the notions of a U.S. corporation, U.S. capital, U.S. products, and U.S. technology.

(Reich, 1991: 3, 8)

People are not only increasingly interconnected; they are interdependent as the following narratives generated by the World Bank illustrate:

Joe lives in a small town in southern Texas. His old job as an accounts clerk in a textile firm, where he had worked for many years, was not very secure. He earned $50 a day, but promises of promotion never came through, and the firm eventually went out of business as cheap imports from Mexico forced textile prices down. Joe went back to college to study business administration and was recently hired by one of the new banks in the area. He enjoys a comfortable living even after making the monthly payments on his government-subsidized student loan.

Maria recently moved from her central Mexican village and now works in a U.S.-owned factory in Mexico’s maquiladora sector. Her husband, Juan, runs a small car upholstery business and sometimes crosses the border during the harvest season to work illegally on farms in California. Maria, Juan, and their son have improved their standard of living since moving out of subsistence agriculture, but Maria’s wage has not increased in years; she still earns about $10 a day but does not complain because she has heard rumors that the company is considering moving the factory to China.

Xiao Zhi is an industrial worker in Shenzhen, a Special Economic Zone in China. After three difficult years on the road as part of China’s floating population, fleeing the poverty of nearby Sichuan province, he has finally settled with a new firm from Hong Kong that produces garments for the U.S. market. He can now afford more than a bowl of rice for his daily meal. He makes $2 a day and is hopeful for the future.

The complex relationships revealed in this anecdote would have been unthinkable 30 years ago.

Although the outcomes in this tale are positive—Joe secured a position at a bank and earns a comfortable living; Maria and her family improved their standards of living; and Xiao Zhi escaped poverty—not everyone benefits from globalization. Although the world is increasingly flat with capital crossing borders in nanoseconds in the pursuit of the highest rate of return and corporations locating operations where labor markets, tax codes, and regulatory regimes are most favorable, it is not necessarily increasingly fair.

In a hypothetical sequel to the World Bank narratives, the bank where Joe worked leveraged its portfolio with uncollateralized debt and had to close its doors at the height of the global financial crisis. With no income and a mortgage that exceeded the value of his house, Joe was forced to file for bankruptcy, but he still owes $830 per month on his student loans. He was fortunate enough to find a part-time job at a Wal-Mart warehouse, but with a one-way commute of 56 miles and gas prices nearing $4 per gallon, he cannot afford health insurance.

Juan was detained by border patrol and has joined approximately 390,000 other illegal immigrants incarcerated indefinitely in U.S. detention centers. The recession bloated inventories and decreased the demand for textiles produced in the factory where Maria worked. When she was laid off, she was forced to withdraw her son from school, move in with relatives, and return to subsistence farming.

And poor Xiao Zhi contracted a skin infection when he was forced to handle chemicals in the factory without protective gloves. The floor manager fired him when he could no longer maintain the required pace of production. After many failed attempts to secure another job in Shenzhen, he returned to Sichuan province but remains hopeful that the herbal remedies prescribed by the village doctor will heal him sufficiently so, one day, he will be able to earn $2 per day again.

1.1 Studying the World Economy

How can one make sense of these stories? On the surface, cause-and-effect seem straight-forward—the demand for textiles declined; Maria lost her job—but in the undercurrent one discovers a complex array of forces that have broad and dramatic effects that can often produce surprising and unexpected results. Deciphering the impact of those forces, interpreting their local, regional, and national implications and how they alter the contours of the economic landscape is the job of the economic geographer.

What are the implications of the Arab Spring; persistently high unemployment rates in EU countries such as Italy and Spain; the AIDS pandemic in Africa; continued environmental degradation in China; increased immigration to the EU from countries in North Africa and the Middle East; growing income inequality and increasingly polarized political landscape in the United States; technological advances such as fracking that enable the extraction of previously unprofitable carbon fuels; and the greater magnitude and frequency of natural disasters?

In addition to these headline-grabbing phenomena, what are the local, regional, and national implications of less newsworthy but equally profound changes in the world economy such as resource grabbing in Africa by developed countries, the rapid spread of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in agricultural production, and technological advances that have enabled cost-effective 3-D printing?

How can we interpret the significance of specific changes that have been occurring in the world’s economic landscapes: The deindustrialization of traditional manufacturing regions (for example, the Rustbelt around the Great Lakes in the United States, northern England, the Ruhr region in Germany), the economic revival of formerly “lagging” regions (for example, New England, Bavaria), the spread of branch plants in the towns and cities of some NIEs (for example, Taipei, Seoul), the emergence of high-technology complexes (for example, Silicon Valley in California, the Research Triangle in North Carolina), the consolidation of global financial and corporate control functions in a few cities (London, New York, Tokyo), and the unprecedented rates of urbanization in China’s coastal regions?

Our task is to develop an understanding of the general economic forces and socioeconomic relationships within the world economy and of the unique features that represent local and historical variability.

But first we need to clarify the use of the terms “general” and “unique” as well as a third term, “singular”:

• General: Widespread phenomena, such as migration or colonialism.

• Unique: Distinctive phenomena—where there are no other instances of it—but its distinctiveness can be explained by a particular combination of general processes and individual responses. An example of this would be the migration streams prompted by the famine in Ireland in the mid-1800s. The general processes that precipitated the famine were environmental (potato blight) and governmental (laissez-faire policy); in response, many people emigrated, including to the United States.

• Singular: Distinctive phenomena that cannot be accounted for by combinations of general processes and individual responses. An example would be the growth of the automobile industry in Detroit. With no established pattern of manufacturing, automobile manufacture could have developed in any number of cities; but Detroit was Henry Ford’s home town (his father had emigrated to Michigan from Ireland to flee the famine), and he put his ideas into practice there.

With these concepts in hand, we can begin to map some of the interrelationships between economic organization and spatial change.

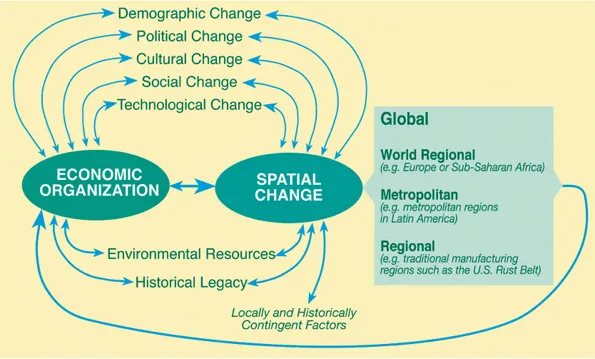

Figure 1.1 shows that economic organization, while critical to spatial change, is implicated with demographic, political, cultural, social, and technological change. Many important interactions also emerge, for example, between political and cultural change and between locally contingent factors and spatial change.

Figure 1.1 The inter-relationships surrounding economic orga...