- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

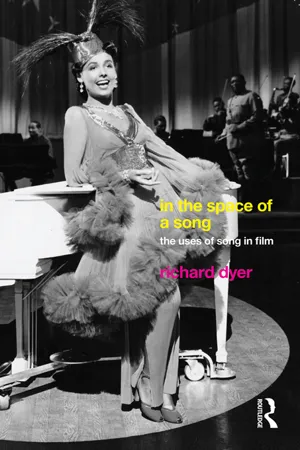

Songs take up space and time in films. Richard Dyer's In the Space of a Song takes off from this perception, arguing that the way songs take up space indicates a great deal about the songs themselves, the nature of the feelings they present, and who is allowed to present feelings how, when and where. In the Space of a Song explores this perception through a range of examples, from classic MGM musicals to blaxploitation cinema, with the career of Lena Horne providing a turning point in the cultural dynamics of the feeling.

Chapters include:

- The perfection of Meet Me in St. Louis

- A Star Is Born and the construction of authenticity

- 'I seem to find the happiness I seek': Heterosexuality and dance in the musical

- The space of happiness in the musical

- Singing prettily: Lena Horne in Hollywood

- Is Car Wash a musical?

- Music and presence in blaxploitation cinema

In the Space of a Song is ideal for both scholars and students of film studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access In The Space Of A Song by Richard Dyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Music1

Introduction

Something About Singing

Oh sing unto the Lord a new song: sing unto the Lord, all the earth.

(Psalm 96:1, c.1 BC)1

Orpheus with his lute made trees,

And the mountain tops that freeze,

Bow themselves, when he did sing.

(Sung by a maid to Queen Katherine in Henry VIII, 1613)2

Sie kämmt es mit goldenem Kamme,

Und singt ein Lied dabei;

Das hat eine wundersame,

Gewalt’ge Melodei.

[She combed her hair with a golden comb

And sung a song as she did,

That had a wonderful

Powerful melody.]

(Die Lorelei, 1822)3

Shout! Shout!

Up with Your Song!

(Suffragette anthem, 1911)4

There are many songs about songs, and thus there are and have been many singers singing about singing. Such songs and singing are rarely ironical, self-reflexive, estranging or postmodern. They are mostly whole-hearted, full-throated, unabashed affirmations of the feeling of singing. Some harness singing to other feelings: worship, love, lamentation, high spirits. Many sing of singing for the sake of singing, just as some give way to pure semantic-free vocal utterance: a hey and a ho and a heynonino, ta-ra-ra boom-de-ay, da-doo-ron-ron-ron da-doo-ron-ron. Singing about singing declares that there is something about singing. Films can build and expand upon that sense of something, not least in the way space and time are handled in relation to it, in the process indicating and contributing to a given culture’s perception of what that something about singing is and what’s at stake in it.

Song is often apprehended as something magical. Angels sing and bring to earth a glimpse of the transcendent: God, eternity, heaven, paradise. Sirens, mermaids and the Lorelei sing and lure men to a watery grave. Sung mantras take the singer to a higher spiritual plane. The magical power of song lingers at the core (or second syllable) of two of the standard English words for magical effect: enchantment and incantation. Song is the medium of choice of religion and witchcraft. Even if we do not believe literally in the supernatural, we may still recognise in such images and practices a sense of the power of vocalising in a way different to speech. We know it too in more everyday terms: lullabies send the fretful to sleep, serenades seduce, psalms and hymns bring believers closer to God and each other, calls summon believers to prayer, football chants create solidarity and encourage victory, marching songs keep soldiers marching and work songs workers working.

There are many ways of accounting for this sense of song. In a series of aphorisms on the voice, the seat of song, Meredith Monk (1976: 56) wrote of it as ‘a direct line to the emotions’. Song, like all art, is at the intersection between individual feeling and the socially and historically specific shared forms available to express that feeling, forms that shape and limit and make indirect what can be expressed and even with any degree of consciousness felt. There is something outside culture – the body has its ways, the mind its operations, the physical and psychological senses their responses – but the moment there is utterance we are in the realm of culture, of indirection. Yet we may all the same apprehend song as a direct line to feeling. Song is close, perhaps closer than most other aspects of music or most other arts, to the pre-semiotic: to breath and the unpremeditated sounds of crying, yelping, whimpering, and to such not-quite-spontaneous (or not always, perhaps not often) vocalisations as keening, laughter and orgasmic yells and the special registers of whispering, hissing, calling and shouting, as well as to mumbling and stuttering. Because birds, whales and other creatures sing, we may feel our singing connects us to nature in a special way. Song may well be, or be felt to be, one of humanity’s first means of communication (Potter 1998: 198); it may take us to the first voice we hear, with its coos and teases as well as its lullabies.

The sense of song’s venerability – its connection to first and abiding sounds – may also inform the experience of secular transcendence in song identified by Mark Booth in The Experience of Songs. He suggests (1981: 206) that song provides a ‘glimpse of authentic togetherness … offering us the experience of unity with what seems to lie apart from ourselves’. This is not primarily an argument about community or mass singing, or singing in unison or harmony or contrapuntally, all of which enable different experiences of togetherness. Rather, in song and singing ‘musical tones transform speech away from the presupposition of separations among speakers, hearer, and object of discourse’ (18) and thus dissolve the boundaries between the self and others and take people into a realm of reality other than the separate and sequential experience of time and space in ordinary reality.5 This provides a gloss on the specialness of songs and singing as well as opening out onto the issues of their relation to time and space.

A number of factors, beyond the various kinds of explanations just given, account for the specialness – or at the least, the particularity – of song and singing: the physical pleasure of singing, its uncanniness, its extremely rich semiotic mix of words, music and voice.

Not everyone takes pleasure in singing, doing it or listening to it, and many wish they could do it better. Yet it is common to hum, whistle, la-la as you go about your business – sounds that serve no purpose and generally express nothing very much in particular beyond the enjoyment, the comfort or cheer of making them. Singing in temple or church, in carriages, coaches or sleighs, at football and other sports matches, in drunken array, there is nothing unusual about any of these, and, if they do also sometimes have other ostensible purposes (prayer, urging on), they are also a joy. Only in very particular circumstances (at religious gatherings, perhaps, or in situations where you are pressurised to join in or be a spoilsport) does anyone have to sing: you do it for the sake of doing it, and pleasure in others singing in part derives from one’s knowledge of the pleasure of singing. Gino Stefani (1987: 23–4) argues that pleasure is intrinsic to singing, because of what is physiologically involved in both producing and hearing song:

A singing voice corresponds to the principle of pleasure, as a talking voice does to the principle of reality. Oral melody is the voice of pleasure: nature teaches us so from childhood. Why? First, because of the conditions of production: a pitched voice requires relaxation of the muscles involved in phonation, and this implies an emotive state of quiet, peace and tenderness in the person. […] Secondly, pleasure is also to be found in perception: not only because of the transmission of this state of ease through the voice, but more radically because such a type of voicing requires less effort to listen to; in fact, singing is an easier message for the brain to decode than is speaking. Just as the line of speech, filled with articulations by consonants, is similar to the movement of walking, so the line of vocal melody, being continuous, flowing, relaxing and free from resistance, is similar to the movement of flying. Flying and dreaming: the longing to escape, the pleasure of escape from harsh reality; movement in slow motion, wide and fluid; power without obstacles.

Part of the pleasure of singing – whether in terms of how well one sings or of one’s delight in others’ ability – resides in mastery. Songs can be more and less demanding to sing, be sung with more and less finesse, security or surprise. Simon Frith (1998: 193) writes of

the sheer physical pleasure in singing itself, in the enjoyment a singer takes in particular movements of muscles, whether as a sense of oneness between mind and body, will and action (a singer may experience something of the joy of an athlete) or through the exploration of physical sensations and muscular powers one didn’t know one had.

Judy Garland’s cocked eyebrow and little laugh at the end of the ‘The Man That Got Away’ (see Chapter 3), a song whose lyrics and underlying tread are grim and despairing, indicates the pleasure in a song well sung, the voice tone mellifluous, the high notes reached and held, the rhythms of the melody ridden with ease. On the other hand, Lata Mangeshkar (like perhaps Joan Sutherland or Ella Fitzgerald) has a voice of seemingly effortless pitch and purity, the very lack of any sense of effort being part of what allows her voice to seem sublime and even transcendent (see below).

Song and singing are such common activities that it may seem perverse to suggest that there is also something uncanny about then, but this too relates to the sense of their specialness and their lending themselves to the supernatural perceptions and practices noted above. In part, the very fact that song is sound opens up the sense of the uncanny. A recent collection of philosophical essays on the perception of sound (Nudds and O’Callaghan 2010) explores the problem of deciding where, in perception, sounds are: at their source? in our ears? all around – that is, all around? moving in a particular direction or flooding space? Speech, animal and machine sounds are so anchored in their source and in practical identification that this may not bother us most of the time, but other natural sources are less straightforward. Where, for instance, is the wind that it produces such sounds, the wind, which is readily associated with breath and song? Song compounds this by how far the sound of singing can travel, even without the aid of mechanical amplification. There is something almost freakish to stand near an opera singer, especially one of slight or elegant build, and observe what an extraordinary, big, reaching sound they can produce. Contemporary audiences were astounded at Bessie Smith’s ‘ability to fill an auditorium with her voice alone, unaided by a microphone’ (Antelyes 1994: 216), with this perhaps becoming all the more astonishing in the context of the possibility of amplification. As Danny Barker observed, Smith ‘could fill it up with her muscle and she could last all night. There was none of this whispering jive’ (quoted in Antelyes). Yet mechanical amplification also both normalised and made possible other uncanny perceptions, notably the fact that one could hear the intimacy of crooning and that ‘whispering jive’, even if one was not near it. Much of the handling of space in relation to song in films at once exploits the magic and downplays the strangeness of this ability to hear song where and how it might not necessarily be heard.

Song may also be formally uncanny. It imposes on vocal production musical time – rhythm, tempi, overall length, the sense of melodic ending – over against both the underlying, ongoing, undivided flow of time and the organised, analytical time (minutes and hours, deadlines, timetables) of practical life. There is something odd about harmony, whereby two (or more) distinct notes exist as ‘apart but simultaneous’, and of ‘tune, where tones move around somewhere and come back to rest in some invisible place’ (Booth 1981: 18). Song, as befits an oral art, makes great use of repetition and redundancy and thus has an overall tendency towards a sense of stasis, towards not going or getting anywhere, to a sense of tableau, of suspended time (Booth 1981: passim). This is highly suggestive in the context of time and space in film.

Pleasurable and uncanny, song is also a particularly rich semiotic mix for the statement of feeling. Because they have words, songs can name and ground emotions; because they involve music, they can deploy a vast, infinitely nuanced range of affects; because they are vocally produced, they open out onto physical sensation.

The words of songs can do more than name and ground emotions. They can tell stories, describe landscapes, promote political positions, make philosophical statements. However, even when not done in song, all of these, like practically all human utterance, have an emotional dimension, and this is usually even more to the fore in poetry, of which song lyrics are a particular form (to say nothing of the long tradition of setting pre-existing poems to music).

Words name emotions. To take only one of the more favoured emotional topics and only English language examples:

Love

My Love

I Love You

Do I Love You?

Love the Way You Lie

With Love from Me to You

What’s Love Got to Do with It?

Love Lifts Us Up Where We Belong

P.S. I Love You

In Other Words, I Love You

Songs do not need to use the word for an emotion in order to indicate it very precisely: there are many love songs without the word ‘love’ in them. There are also categories of song defined by their emotional address: hymn, lament, lullaby, serenade.

Naming an emotion indicates and specifies it. It brings it into verbal discourse, into the most privileged form of recognition, reflection and scrutiny in modern cultures. On the one hand, it limits the emotion – it’s love, not anger or depression or just feeling good. On the other hand, it indicates something vast. The song ‘Love’, after listing the many things love can be, such as amusing, insane, a joy for ever, a dirty shame, concludes that ‘love is almost never ever the same’. (Curious, that ‘almost’ with the insistent ‘never ever’.)6

The simplest lyrics provide further nuance to the emotion. The Perry Como hit ‘I Love You (And Don’t You Forget It)’7 merely repeats these words over and over. There is wit here: repeating the same refrain so often means it is not liable to be forgotten. There is also self-reflexivity in the one other line the song has: ‘That makes seven times that I said it’. There are also hints of something else. ‘Don’t you forget it’ is a phrase usually used a little threateningly, but the repetition here may also hint at anxiety, that maybe the loved one will forget that they are loved. This is already a complex set of emotions, suggesting that, beyond the declaration of love, it is not altogether clear what other emotions are fully or at all in play. The light-heartedness of the song, potentially in the wit and self-reflexivity, more evidently in the up-beat tempo of the music, itself complicates matters, for light-heartedness and humour are often a way of dealing with difficult and aggressive emotions. All that in an apparently straightforward song in the supposedly simplest of song genres.

Words also ground the emotions they state, which in turn means they indicate space and time. At the simplest and also most inescapable level, they entail grammar, including person and tense, both of which are space-time dimensions. Person: I love you, You’re just in love, Your eyes are the eyes of a woman in love, She loves you, He loves me, Love lifts us up. Tense: I love you, Love lifts us up, When I fall in love (it will be forever), It was a lover and his lass, Love me (that’s all I ask of you), If I loved you (with the examples encompassing present, future, past, imperative, subjunctive). All imply spatial positions – for I or you or she or he must be somewhere – as well as temporal ones. Words may make this grounding more specific, indicating where the singer is or was, what time of day or the year it is and so on. The less spatial and temporal indicators the lyrics give, the more there may be a sense of the emotion floating free of such concerns, perhaps to suggest transcendent states of love, ecstasy, spirituality.

Words do not only have semantic dimensions. They have sounds and rhythm, with potentially wide affective qualities, and they are always, even when spoken, coming out of a body, involving effort, muscular activity and breath, sensations located in space and taking time to produce. With music, the affective is to the fore.

Music deploys a very wide and nuanced range of affective timbres, vastly beyond the reach of language (or musical notation) to describe, nor readily separated into analysable components. Suzanne Langer (1953: 27) begins to give a list of music’s affective qualities that lie before or beyond any more specific, nameable emotion: ‘forms of growth and of attenuation, flowing and stowing, conflict and resolution, speed, arrest, terrific excitement, calm, or subtle activation and dreamy lapses – not joy and sorrow perhaps, but the poignancy of either or both’.

This may be linked to the flux of feelings experienced in the womb and in very early childhood, before these have been organised into more discrete categories. It is perhaps comparable to the kinds of pleasure, interest and curiosity...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The perfection of Meet Me in St. Louis

- 3. A Star Is Born and the construction of authenticity

- 4. ‘I seem to find the happiness I seek’: heterosexuality and dance in the musical

- 5. The space of happiness in the musical

- 6. Singing prettily: Lena Horne in Hollywood

- 7. Is Car Wash a musical?

- 8. Music and presence in blaxploitation cinema

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index