eBook - ePub

Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia

Documentation, Denial, and Justice in Cambodia and East Timor

- 363 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia

Documentation, Denial, and Justice in Cambodia and East Timor

About this book

Two modern cases of genocide and extermination began in Southeast Asia in the same year. Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge regime ruled Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, and Indonesian forces occupied East Timor from 1975 to 1999. This book examines the horrific consequences of Cambodian communist revolution and Indonesian anti-communist counterinsurgency. It also chronicles the two cases of indigenous resistance to genocide and extermination, the international cover-ups that obstructed documentation of these crimes, and efforts to hold the perpetrators legally accountable.The perpetrator regimes inflicted casualties in similar proportions. Each caused the deaths of about one-fifth of the population of the nation. Cambodia's mortality was approximately 1.7 million, and approximately 170,000 perished in East Timor. In both cases, most of the deaths occurred in the five-year period from 1975 to1980. In addition, Cambodia and East Timor not only shared the experience of genocide but also of civil war, international intervention, and UN conflict resolution. U.S. policymakers supported the invading Indonesians in Timor, as well as the indigenous Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Both regimes exterminated ethnic minorities, including local Chinese, as well as political dissidents. Yet the ideological fuel that ignited each conflagration was quite different. Jakarta pursued anti-communism; the Khmer Rouge were communists. In East Timor the major Indonesian goal was conquest. In Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge's goal was revolution. Maoist ideology influenced Pol Pot's regime, but it also influenced the East Timorese resistance to the Indonesia's occupiers.Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia is significant both for its historical documentation and for its contribution to the study of the politics and mechanisms of genocide. It is a fundamental contribution that will be read by historians, human rights activists, and genocide studies specialists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Genocide and Resistance in Southeast Asia by Ben Kiernan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Genocide & War Crimes. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Genocide and Resistance

1

Wild Chickens, Farm Chickens,

and Cormorants: Cambodia’s Eastern

Zone under Pol Pot1*

In his 1981 memoir of life in Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea, entitled Cambodia: 1,360 Days!, Ping Ling described the newly victorious Khmer Rouge as they forcibly emptied Phnom Penh, capital of the defeated Lon Nol regime, of its two million residents. From the viewpoint of a civilian evacuee, Ping Ling provided a glimpse of the contrasting roles of the different Khmer Rouge units that occupied the western and eastern banks of the Tonle Sap River:

30 April, 1975: No fresh news at the temple today, except rumors spread by the blackshirts themselves that the blackshirts on the other side of the river are worse than those on this side… We really don’t know what to believe, no one dared ask. 1 May, 1975: The embankment going down to the boat was steep and far, with only a wooden plank a foot wide between the boat and the wet mud bank. Extraordinary how everything did go across that plank, even pigs; except for one incident where a pregnant woman, carrying a baby in one hand, her basket containing food in the other, and a bundle of clothing on top of her head, suddenly seemed to lose her equilibrium.. .she let go of the basket of food and that bundle on her head toppled into the river. But she did keep the baby in her other hand. A number of blackshirts were nearby, looking calmly on without lending a hand. One good thing, though; they didn’t laugh.

Two hours later, we arrived at a small wharf. ‘Greenshirts’ instead of blackshirts could be seen on this side of the river. They were at the end of the planks where the passengers were descending, helping everyone who was overloaded with things in their arms. Carrying babies for the mothers, they even helped to carry the invalid ashore. So much for those blackshirts’ propaganda on the other side. They even tried to steady me by holding on to my arms loaded with bundles. They were helpful good commie soldiers.

In September 1975, the former customs officer Sok Sopha crossed the Mekong to the Eastern Zone and also found what “seemed like another world.” Sopha recalled:

I was met by local people and militia who each gave me a tin or two of milled rice, 25 kgs. in all. They all asked me what things were like back there…. I knew these people were different but I dared not say so. I could see that [defeated] former Lon Nol soldiers were still alive and was told that even generals had been spared here. The people were only working three days per week and could search for dispersed friends and relatives and barter for goods on the other days. Buddhist monks took part in the Pchum Ben festival in September. Very large canals had been dug, the rice crops were big, and there was a good deal of palm sugar and pig-raising. Nurses visited from village to village to tend to the sick. The people liked the Eastern Zone cadre, they were united as one. There were no classes as in the Pol Pot areas: everybody was a soldier for the revolution. If the Eastern Zone group had won control throughout the country in 1977, things would not have happened as they did.

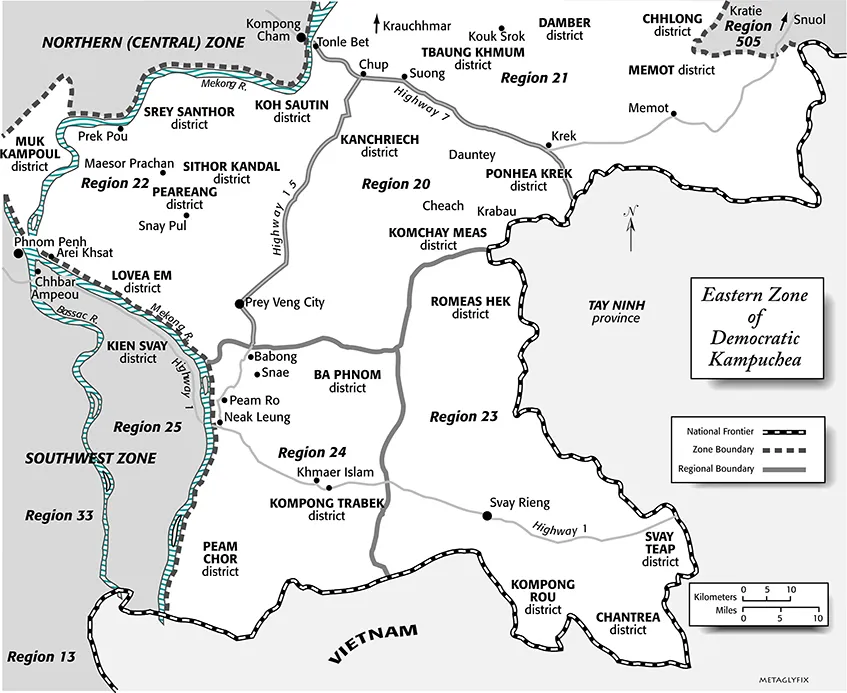

Sopha made several such visits, but always to the same village, and his idyllic picture of the large area that comprised the Eastern Zone of Democratic Kampuchea (DK) in 1975 is an extrapolation from that. Although other witnesses confirm that urban evacuees in the East were accorded considerable liberty to search for relatives and friends,1 no other evidence exists that the working week was limited to three days; some executions of former Lon Nol military and others did occur there; there was even starvation in one or two eastern districts in the first six months after April 1975; and the last remaining monks were all defrocked by the end of 1976. But the contrast which Sopha draws between the two sides of the Mekong was nevertheless real, and so was the 1977 turning point which he identifies. In 1975-76, at least, there were substantial differences between the Eastern Zone and other zones of Cambodia, in terms of living conditions and the implementation of revolutionary policy. In the words of a Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) “Center” (mocchim) internal report, dated 20 December 1976: “In 1976 the labor force was feeble. It was only in the East that it was not feeble.”2 In a detailed study of the DK economy, Marie Martin has noted that in Prey Veng and Kompong Cham, the major eastern provinces, engineers evacuated from the cities were employed to design the irrigation projects built there. In Prey Veng and the other eastern province, Svay Rieng, pre-revolutionary projects and project designs formed the basis for successful post-1975 irrigation schemes.3 This was not the case for other Zones, whose leaders tended to reject non-revolutionary “experts.”

In this essay I have tried to piece together the story of the main segment of Pol Pot’s “internal opposition” – largely a loyal, even unwitting opposition at first, but one that by May 1978 was driven to outright rebellion. By then or beforehand, the Pol Pot group or CPK Center had decided that the Eastern Zone cadres and population possessed “Khmer bodies with Vietnamese minds” (khluon khmaer khuo kbal yuon), and it began a large-scale program to eliminate them. Over 100,000 perished in the next six months – the worst single atrocity of the DK period. Paradoxically then, the area almost universally considered by Khmers as the safest place to live in DK until 1977, became by far the most dangerous in 1978. Further, the two key themes of regional variation and the centralization of control can both be found in the history of the Eastern Zone, and it is there that tension between them was most evident. It was the culmination of a process of Center intervention in the Zone that began in earnest around mid-1976 and nearly annihilated the veteran Eastern Communists, although they had the last say in 1979 when their remnants, led by Heng Samrin and Chea Sim, and backed by the Vietnamese army, returned to positions of power. Study of the Eastern Zone is therefore useful for an understanding of contemporary Khmer politics. It also fills gaps in our knowledge resulting from the fact that until 1979-80, few refugees from the Zone reached the distant Thai border to make their experiences known to the Western world.

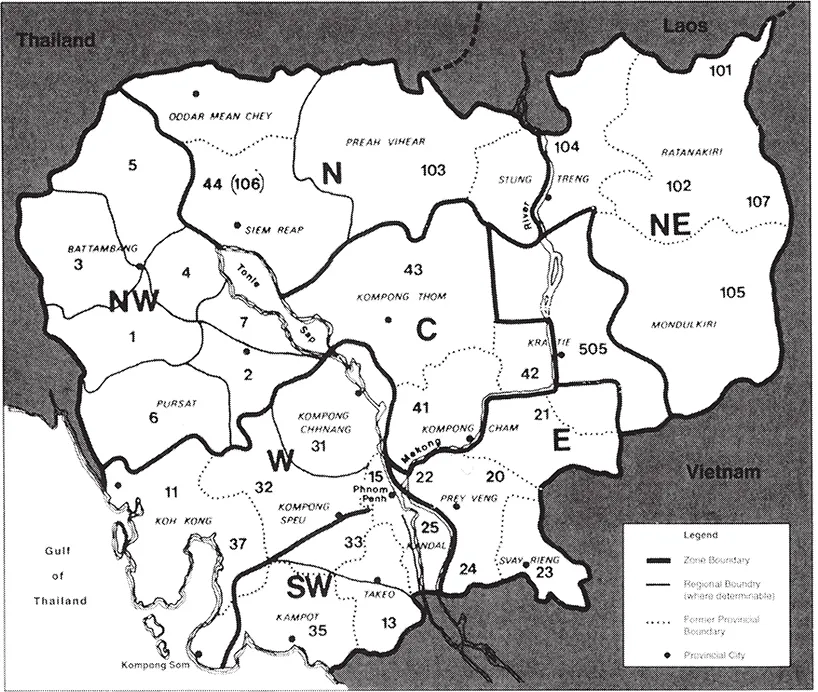

My research in this chapter is based on eighty-seven interviews conducted in the period 1979-81, with people who had lived in all five Regions (numbered twenty to twenty-four) of the Eastern Zone between 1975 and 1979. They include forty “base people” (neak moultanh, i.e., those, mostly peasants, who had lived in CPK-held areas during the 1970-75 civil war), twenty-seven “new people” (neak thmei, those evacuated in April 1975 from the towns, held until the end of the war by the Lon Nol regime), and twenty revolutionary cadre. Thirty-three of the base people I interviewed were peasants, and twenty-three of the eighty-seven interviewees were women.4 In the absence of a more substantial survey, a conclusive appraisal of social conditions in the East cannot be attempted. In what follows I will summarize the evidence available to me as of 1981, and illustrate it with some verbatim accounts. I will discuss at greater length the political struggles that took place there, including local resistance to the genocide. What we know of these suggests that the reasons for the differences between the Eastern Zone and elsewhere in DK were indeed political, at least in part, and it throws some light on the moderate socialist policies adopted by the Heng Samrin government after 1979.

For over a decade, however, Heng Samrin and Chea Sim both declined my requests for interviews. Chapter 2 reproduces my 1991-92 interviews with them.

Executions and Starvation in the Eastern Zone: Summary of Data

1975-76

Of the sixty-seven interviewees who were not Khmer Rouge cadre, ten mentioned specific victims of killings by Eastern Zone cadre in the years 1975 and 1976, numbering over 190 victims in all. At least five of the ten were not eyewitnesses to the killings they mentioned, so there is no certainty about all of them. On the other hand, thirteen interviewees also reported people disappearing after being taken away “to study”; and from the testimony of five or six such people I interviewed, some of those apprehended in this way were executed. (Most were released – especially in the southern Regions 22, 23 and 245 – and large-scale deaths among those who remained in detention do not appear to have taken place before late 1976.)

Of the 190 reported victims, thirty were reported from a single district: Chantrea, in Svay Rieng province of Region 23.6 Another eight to ten deaths occurred during an abortive uprising led by former Lon Nol regime figures, in Region 22 in November 1975. About 130 of the reported executions were dated at mid- to late 1976. For the sixteen months after April 1975, then, specific executions reported by the sixty-seven non-cadre interviewees outside of Chantrea district numbered about twenty, to which must be added seven victims of a self-confessed executioner whom I also interviewed. There were, obviously, more executions in the hundreds of Eastern villages not covered by this sample and these probably numbered in the thousands. Six interviewees mentioned in general terms the types of people liable to execution in that period: “intellectuals and Lon Nol officers;” “most military, officials, and rich people;” “many Lon Nol officers;” “only well-educated people;” “one or two who refused orders or were lazy;” and “not many like in 1977,” when there were fewer again than in 1978. However, twenty-nine of the non-cadre interviewees asserted that there were “no killings” of people from their villages in 1975-76; another ten mentioned none; ten described uncertain circumstances that may have led to executions, and two others mentioned executions limited to revolutionary cadre.

Starvation took a heavy toll in two of the interviewees’ villages in the year 1975 – twenty deaths were reported in one Chantrea village, fifty in a village in Memut (Region 21). Apart from these cases, however, all accounts agree that rations distributed and food available were adequate for basic nutrition in 1975 and 1976.

Most of the interviewees who reported executions or starvation in their villages in 1975-76 described the revolution and their conditions of life at that time as “no good.” Of the other fifty-five non-cadre interviewees, eleven expressed no opinions on the subject. Among the remaining forty-four, a range of views was expressed, usually quite complex and nuanced. Seven described the revolution and conditions of life in that period as “no good” primarily because of hard work and low rations but reported no executions or starvation. Another seven described them as something between (or, in different respects, both) “no good” and “tolerable” (kuo som) or “all right” (kron bao). Twenty-one described them in terms such as “tolerable” or “all right,” and nine in terms such as “good” (la’o) or “not a problem” (ot ey te). Further, ten of the new people who did not hold such a view themselves, expressed the conviction that in 1975-76 the base people (i.e., the local peasants) in their village were supporters of the revolution.

There are several reasons for these rela...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part 1: Genocide and Resistance

- Part 2: Description, Documentation, Denial, and Justice

- 3: War and Recovery: Reporting from Cambodia, 1979-90

- Bibliography

- Index