![]()

Part I

Models and theories

![]()

Chapter 1

Visuoperceptual-cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease: adapting a dementia unit

Gemma Jones, William van der Eerden-Rebel and Jeremy Harding

Overview

This chapter presents Alzheimer's disease (AD) as a simultaneous visuoperceptual and cognitive illness, with a view to educating care-givers about the types of visual deficits and resultant difficulties that persons can experience. Typical visuo-cognitive errors made by persons with AD throughout the illness process are presented to illustrate the ever-changing nature of the visual world to a person with AD. This chapter also provides possible ways of making care environment adaptations to aid in the perception of key visual information.

Research findings about pathological changes to the visual system in AD and the resulting perceptual deficits are numerous and have many implications for assessment and care. Clinicians have been slow to respond to this information because the link between vision and cognition in AD was not well understood (nor detectable with conventional sight tests measuring primarily acuity and visual fields), even though it was known that the brain areas for control of memory and detailed visual perception (which lie next to each other in the medial temporal lobe) are the first structures damaged in AD. The presence of additional visual pathology and/or age-related visual deficits (which may be present before, simultaneous with, or later on in the AD process, depending on the age of onset) has also contributed to the difficulty in establishing the link between visuoperceptive and cognitive deficits in AD.

The progressive visuoperceptual deficits in AD require specials tests to measure them. Tests to detect visual deficits in AD measure contrast sensitivity, visual attention, object and facial recognition, colour and depth perception, figure/background discrimination and the eye movements needed for scanning moving and stationary items in the environment and for reading, among others. Eventually, visual phenomena in AD include ‘looking but not seeing’ and Balint's sign. These deficits cannot be corrected simply by prescribing glasses, but require a more practical range of interventions, starting with improved lighting levels, increased figure background contrasts and colour saturation for important visual cues.

The neurofibrillary tangle and betaamyloid plaque pathology, which characterize AD, slowly damage many structures in the visual system (retina, optic nerve, lateral geniculate nucleus, inferior colliculus, the primary visual cortex and associative visual cortices). Damage extends to both the ‘conscious Primary Visual Pathway’ and the less understood ‘unconscious (automatic seeing) Tectal Pathway’; the latter is providing new explanations for early, but complex visuoperceptual symptoms that include difficulty in shifting visual attention and guiding responses to events.

A pilot study is presented to show the effects of making visual environmental changes to an 11-bed dementia unit; parameters included increasing ambient light levels, increasing the saliency of familiar cues, providing a variety of familiar seating options and arrangements, enhanced figure background contrast of key environmental features and lowering signs and new decorations to within the visual field of residents. An immediate decrease in ‘lost-wandering’ and ‘wanting to go home’ behaviour was observed in conjunction with an increase in social interactions with other residents and care-givers, and engagement with familiar household objects and activities was observed. The changes also provided family visitors with more sociable seating and activity options.

Initial examples of visuo-cognitive difficulties in Alzheimer's disease

Below are examples of visual errors made by persons with AD. Note how pervasive and frustrating such events can be during the course of a day, and their potential impact on a person's emotional state.

Mouse in the bin

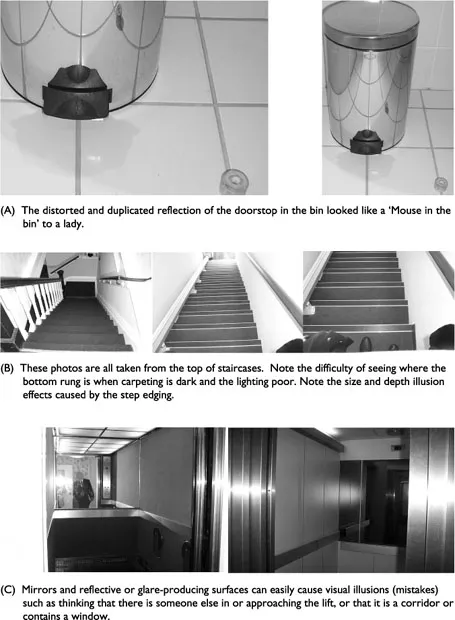

Mrs T, 85, said to staff in the care home ‘There is a mouse in the bin’. They checked and told her that there was none. She pointed to the bin again saying ‘There it is’. A care-giver checked again, and seeing none, reassuringly told Mrs T that ‘this is a clean place and no one has ever reported seeing mice’. Mrs T remained insistent and continued repeating herself. Finally, someone sat next to her and noticed the image in Figure 1.1A. They realized that Mrs T was reporting literally what she was seeing, unable to say ‘the distorted image in the highly reflective cylindrical surface is causing an illusion that makes the doorstop and tile line-curvature look just like a mouse’.

Mrs T would likely have felt understood, though still repeated herself, if staff had replied ‘You're right! It looks just like a mouse in the bin. No wonder you were surprised.’ In this instance, Mrs T was not afraid of mice, and did not seem distressed, but had she been, she may have started screaming and become agitated. (She may even have been thought to be hallucinating.) Had she been frightened, removing the bin from sight, changing her seating and getting a non-reflective bin are three immediate options for removing the possibly offending stimulus from her sight.

Figure 1.1 Visual challenges for persons with Alzheimer's disease.

Mr D always jumps from the third step when coming downstairs

Mr D, 67, could go upstairs effortlessly. His family could not understand why he made such a nuisance of himself when coming downstairs. He literally hurled himself from the third to bottom step, as if jumping from an enormous height, and sometimes fell onto the darkly carpeted landing on his hands and knees (see Figure 1.1B).

When his family realized he was having difficulty seeing and could no longer accurately interpret the shadows on the stairs and the illusions of different lengths and heights of steps, they increased the lighting over the staircase. They also came to help hold his hand more often to guide him when he was going downstairs instead of becoming frustrated by his ‘strange’ behaviour.

He also became aggressive and resistant when his wife tried to get him to sit accurately on the toilet. He hesitated and resisted her help to sit down (being nudged/pushed backward), as if he thought he would fall. His wife also tried to get him to sit on the toilet to urinate because he was often missing the toilet. She had recently discovered several bowel movements just in front of or beside the base of the toilet (suggesting he had not seated himself). She thought he was becoming incontinent. However, installing extra-length extended handrails on either side of the toilet (painted in a bright colour) helped for a number of months. He still needed help at times to position himself correctly in front of the toilet and to make sure he could feel the rim of the toilet against the back of his legs. However, seeing and holding the handrails himself seemed to make him feel safer and more in control than having his wife push him backwards.

The elevator is always full to Mr W

Mr W, 84, was standing in a sheltered accommodation building, waiting for the elevator so that he could return to his room. The corridor was poorly lit and the carpeting dark. When the elevator arrived and the door opened, he mistook his reflection (visible from the three surfaces of highly polished metal inside) for an elevator full of people (see Figure 1.1C). He politely announced that they could go ahead and he would wait for the next elevator. This happened several times in succession and he could not be persuaded to enter the elevator. He began looking for the stairs, but became increasingly flustered angry and lost. (This difficulty could have been helped by removing or covering-over the mirrors, improving the lighting in the lift and putting a lighter coloured flooring in the lift.)

Mr D could not find his yellow fleece jacket

Mr D, 55, is aware of his diagnosis of early-onset AD and welcomes opportunities to discuss how it affects his life. He told of looking for the yellow fleece jacket that was hanging in the wardrobe. After looking back and forth along the length of the clothes-rail several times he became upset that he could not find it and called his wife. She found it immediately and handed it to him. From that point onwards, Mr D told others that he was ‘missing bits of vision’ and explained it as: ‘I feel like I'm going crazy. I know things are there but I cannot see or find them. It's like someone is following me around with an “invisible gun”. They disappear everything I need.’

He was afraid to tell the doctor about this, fearing to be thought ‘crazy’. His wife had not found any references to visuoperceptual problems in the AD literature she had.

Changing the lighting brings back a war memory

Mr P, 74, had been diagnosed with AD for 2 years. In recent weeks he had become distressed each evening near dusk. It started after his wife closed the living room curtains and put the hall lights and table-lamps on in the living room as she was preparing to watch TV. Mr P had started hiding behind the chairs and couch in the living room, would not come out with his wife's prompting and had even urinated there, although during the daytime he used the toilet by himself. Eventually, a connection was made between the change in lighting conditions and his recently worsening ‘disorientation in time’ (he sometimes thought he was back in the war again).

At one point, as an escaping prisoner of war, he had hidden himself in a large-diameter water tunnel for several weeks (hiding and vigilant by day, and leaving briefly to steal food by night). The lighting changes his wife made at dusk produced a comparatively strong glare of light coming through the opened double doors into the [now] dimly lit lounge. This lighting condition must have reminded him again somehow of the (comparatively) strong light at the entrance of the dark tunnel, and passing shadows meaning potential danger. It is also possible that he was not resolving his wife's image correctly against the glare, and hence hid and resisted her efforts to come out from behind the furniture. This could account for his urinating there too.

It seems that his wife had unknowingly re-created similar lighting conditions to a past traumatic event. After realizing that her husband's recent behaviour changes might be linked to misperceiving his environment and re-living a traumatic memory, she tried leaving the overhead lights on in the living room (as opposed to the small table lamps, which produced little light) and kept the hall and toilet well lit. Mr P's seeming ‘perceived fear’ behaviours ceased.

Background

Vision is defined as the process referred to as ‘seeing with our eyes’, which gives us a representation of the world around and the possibility of interacting with it through movement. ‘Perception’ is the process that allows us to provide meaning to the things we see (and otherwise sense, and feel emotionally). Perception enables our building upon and evaluation of memories, and the mak...