![]()

Special Section | Proto Surrealism and Surrealism |

![]()

The Mystery and Melancholy of Nineteenth Century Sculpture in De Chirico’s Pittura Metafisica

Nancy J. Scott, Ph.D.

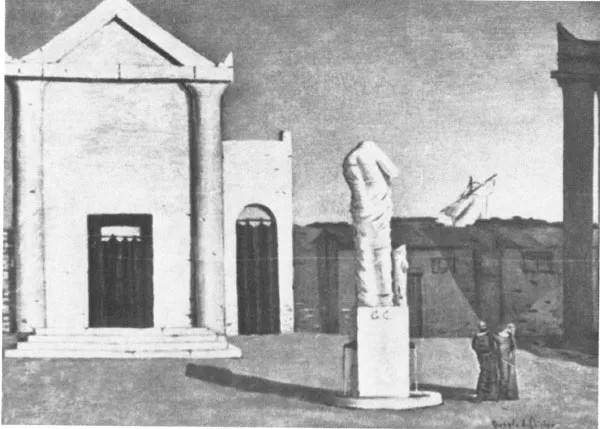

Giorgio de Chirico first painted a piazza populated only by a statue and two shadowy figures in 1910, while he was in Florence. (The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon, fig. 1). Soon thereafter, in the summer of 1911, he and his mother moved to Paris where they remained, together with his brother, until 1915. In Paris, de Chirico continued to paint piazzas that increasingly reflected Italy through the sculptures, which are clearly identifiable as Italian monuments. Indeed, the Piazza d’Italia series flourished throughout the painter’s Parisian period. This part of his pittura metafisica represents the crucial conjunction of de Chirico’s real experience of things he has seen and places he has inhabited with his imagined and dreamlike transformations of those same places and things. Without doubt, it is this conjunction of the real and the imaginary, the product of the years when de Chirico lived in Paris and dreamed of Italy, that gives the pittura metafisica its haunting power. The aim of this article is to aid our understanding of that power, first of all, by suggesting several hitherto overlooked sources for de Chirico’s Piazza d’Italia series–in particular the actual nineteenth century works that stand behind de Chirico’s sculptural inventions–and, second, by tracing the transformations of those sources in the paintings.

Fig. 1. Giorgio de Chirico, The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon, 1910. Oil on canvas. Whereabouts unknown. Reproduced from J. T. Soby (1955).

What follows takes as its starting point a radical, but essential, move away from the traditional view that Turin and, very secondarily, Florence are the Italian cities most important to the painter’s inventions. In point of fact, prior to his sojourn in Paris, de Chirico, who was born in Greece to Italian parents, lived in Italy for only two years, from 1909 to 1911, and these two years were spent first in Milan and then in Florence. The city of Milan, which was de Chirico’s first residence in Italy, has received virtually no attention in the de Chirico literature even though, as will be shown below, there is a strong presence of Milan, both of its statuary and its public spaces, in certain of the metaphysical paintings.1 This neglect of Milan began with de Chirico himself. He referred to Turin in his Memorie della mia vita (1945, pp. 80–81, 94, 101) in several key contexts, to Florence once in another key document on the “revelation of the enigma,” and to Milan quite negligibly (p. 89; Soby, 1955, p. 251). Notably, in the Memorie (p. 81), he described Turin as the place one could best observe Nietzsche’s Stimmung, the profound poetry and mystery of which the painter equated with the long shadows and clear late afternoon light of autumn. Scholars have followed this and other leads and have concentrated on Turin as the city to comb for the real-world counterparts of de Chirico’s inventions (Soby, 1955, pp. 49–50, 70).2 While the incongruities of the objects placed within de Chirico’s pictorial compositions have often been noted as central to the disquieting poetry of his proto-Surrealist imagery, the inconsistencies of what de Chirico wrote and said about sources and places important to his work have not been given the same scrutiny for “poetic” invention.

In fact, we have de Chirico’s word for it that his first trip to Turin was made in the extreme heat of July 1911 to see an exhibition and that illness forced him and his mother to go on to Paris after just two days (1945, p. 94).3 Thus, at least in 1911, the painter obviously did not visit Turin during the long-shadowed days of autumn. Furthermore, he did not return to Turin during his metaphysical period, when all but one of the works considered here were completed. De Chirico was drafted into the Italian army after the outbreak of World War I and was sent directly from Paris to Florence and from there to Ferrara (Soby, 1955, p. 107).

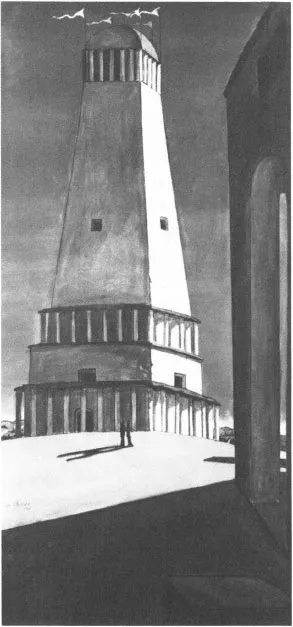

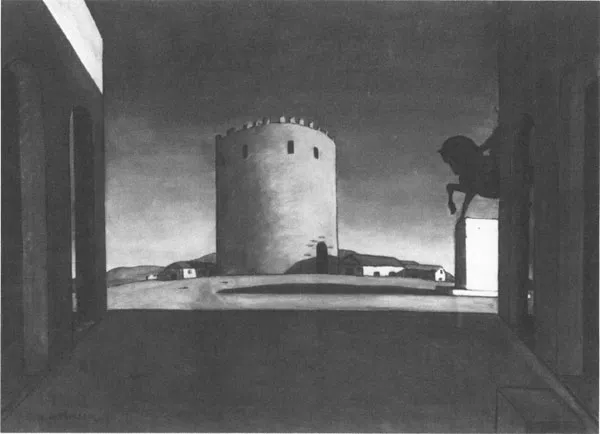

Certainly, there can be no doubt that de Chirico was powerfully drawn to Turin–if more in his imagination than in reality–because of the city’s connections with Nietzsche, which will be explored in more detail below. And there is the strong probability that even his extremely brief stay in Turin may have provided the painter with a fund of visual memories and, perhaps more important, with resonant associations that intensify the symbols chosen from that city. The 19th-century Mole Antonelliana, for example, which clearly dominates Turin’s skyline in early 20th-century photographs of the city, as it still does, seems a logical source for the tricolonnaded structure in de Chirico’s “tower” pictures, such as The Nostalgia of the Infinite (fig. 2, 1913–14), or The Great Tower, 1913.4 So, too, the equestrian monument first seen in The Red Tower (1913) is most definitely the Torinese Monument to Carlo Alberto (1861) of Marochetti (figs. 4 and 5), to be discussed below.

Fig. 2. Giorgio de Chirico, The Nostalgia of the Infinite, 1913—14? (dated on painting 1911). Oil on canvas. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase.

Fig. 4. Giorgio de Chirico, The Red Tower, 1913. Oil on Canvas. The Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. S. R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York. Photo: Robert E. Mates.

Fig. 5. Carlo Marochetti, Monument to Carlo Alberto, 1861. Piazza Carlo Alberto, Turin.

With regard to the vast architectural spaces that have often been given a Torinese source, and which become a necessary subtopic here, it is my contention that de Chirico could have been impressed by arcaded structures in many Italian cities (see note 19) and that the inspiration for piazzas of a vast scale came from a visit the painter made to Versailles, much closer to his actual city of residence while he created the Piazza d’Italia series.

Furthermore, in contrast to his two-day stay in Turin, de Chirico lived in Milan for a year. In his Memorie (p. 89), the painter dismissed his one-year residence in Milan by saying that there he merely “painted Böcklinesque canvasses.” Here I propose new source material in Milan for de Chirico’s pictorial use of sculptures. The shift in focus to Milan and the consequent investigation of the Milanese sculptures de Chirico used as sources inevitably leads to an examination of the meaning of those sources, both in their original contexts and in those new ones de Chirico provided. This second line of inquiry opens up an astonishing range of de Chirico’s associations––psychological, political, and pictorial. To a large extent, the psychological associations are focussed upon a single 19th-century frock-coated statue that de Chirico introduced into his desolate piazzas, a figure which I believe should be understood as de Chirico’s image of his father and, on another level, of his fatherland. The political associations stem from an interpretation of statesmen sublimated in the design of the statue. Finally, the pictorial associations center on Milan’s Brera, where de Chirico saw Raphael’s Marriage of the Virgin (fig. 18), and where, in the courtyard, he could also have seen the statuary that sparked the creation of the frock-coated figure.

The frock-coated statue makes its first appearance in 1913, and by 1914 it has come to dominate the piazzas painted by de Chirico.5 As early as 1910, de Chirico placed a sculpture in the center of a piazza, its back turned to the spectator, in The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon (fig. 1). This is the first painting in which de Chirico uses a 19th-century sculpture though its transformation renders its source (which the painter said was Dante in the Piazza Santa Croce) unrecognizable. Sculptural monuments are generally the only presence in de Chirico’s vast spaces apart from a much smaller pair of figures which, by 1913–15, were reduced to blackened silhouettes. The painter populated his compositions throughout the Parisian period with works of sculpture either from the Greek period or the 19th century. The Greek motifs have been reasonably well identified. For example, a derivation of the recumbent classical figure at the Vatican, long known as Ariadne, dominates major works of the year 1913.6 Moreover, in 1913, a 19th-century equestrian monument makes its first appearance in The Red Tower. By 1914, Ariadne has ceded her place in the lonely piazza to the figure of the frock-coated 19th-century statue.

It is by tracing the frock-coated statue through the chronological grouping of de Chirico’s paintings, as proposed by Soby, that its identity as a father figure emerges so clearly. De Chirico’s father died in Greece when the painter was 17 years old and, up to now, his image has seemed oddly absent from de Chirico’s oeuvre––though his spirit is constantly evoked through the many trains on distant horizons. The reasons for identifying the isolated stone figure in the piazza with de Chirico’s father and thereby solving the problem of this curious lacuna in the painter’s work, will unfold below, confirmed by de Chirico himself in the works depicting the return of the prodigal son (c.f. fig. 19), which he began in 1917 just as his pittura metafisica period was drawing to a close. In these works the statue steps down from his pedestal to embrace the mannequin, which, I argue, is an image of de Chirico himself. Thus, the son is reconciled to the father, whom he perceived as distant, reticent, and embodying those 19th-century values that were at odds with the creative impulses underlying the pittura metafisica. Simultaneously, there is increased evidence in the works of de Chirico’s admiration of Raphael. Indeed, by 1919 de Chirico was thoroughly disengaged from the paintings of his youth, which he would later vehemently condemn, and had embraced the outmoded academic classicism that is in itself a return to 19th-century standards.

The identification of the correct sources for the frock-coated statue is, then, not simply an arcane point of art historical interest. It is not enough to know, as Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco (1982, p. 33) has suggested, that de Chirico uses types of monuments to suggest in a general manner, if an encoded one, the “epic times” of the Italian Risorgimento.7 The examination of the frock-coated sculpture, which appears in at least five major paintings of 1914 and 1915, and the location of its source not in Turin, but in Milan lead to the unlocking of the far more personal side of de Chirico’s iconography through the period of the pittura metafisica, that is, to his imagery of the father. This father image is situated in a dreamlike locale (Gordon Onslow-Ford coined the phrase “Chirico City”). It may be characterized by motifs as diverse as palm trees and distant locomotives, red-brick smokestacks and arcaded facades stretching to distant horizons of unearthly yellow and green or blue tones. This place was created in Paris, made up of memories from the wanderings of de Chirico’s dislocated Italian family: living first in Greece, then returning to their homeland to see Venice and Milan, then to Munich, returning a second time to Italy, where they lived in both Milan and Florence, then to Paris, and finally to Italy again, to Ferrara with the advent of the First World War.

Before turning to my major subject, the proposed source for the frock-coated figure and its meaning, two preliminary subjects claim our attention: first, the hitherto unrecognized role of de Chirico’s actual city of residence, Paris, and its environs, in sparking the creation of Chirico City and, second, a reevaluation of Turin’s importance in the Piazza d’Italia series.

Versailles as Source for the Piazza D’Italia Series

De Chirico’s presence in Paris during the genesis of these paintings must be taken into account. Why was it that in the city of Paris de Chirico began to dream of an Italy of vast squares populated only by statues? His longing for a homeland and consequent sense of identification in Italy may be a psychological explanation. Yet something he saw or experienced in Paris might have triggered the creation of the enormous, desolate spaces that have become de Chirico’s trademark. One quickly rejects a number of possible sites: Fremiet’s Jeanne d’Arc in the Place des Pyramides is in too constricted a place; the Place de la Concorde and that surrounding the Arc de Triomphe are certainly vast, but far too busy with traffic and filled with architectural sculpture to correspond precisely to de Chirico’s vision; the Tuileries exhibits a number of pieces of 19th-century sculpture, but its trees and grassy squares inhibit the feeling of scale and monumental distance that the painter captured.

The anwer, it seems, may be found in de Chirico’s own manuscript of 1913, where so many telling clues are hiding in plain view:

One bright winter morning I found myself in the courtyard of the palace of Versailles. Everything looked at me with a strange and questioning glance. I saw then that every angle of the palace, every column, every window had a soul that was an enigma. I looked about me at the stone heroes, motionless under the bright sky, under the cold rays of the winter sun shining without love like a profound song. . . . Then I experienced all the mystery that drives men to create certain things. (Soby, 1955, p. 247)

The location de Chirico describes would have offered him a view of the vast scale of the square in front of the palace. With its three axially symmetrical roads and few trees or buildings nearby to lessen the impression of grandeur, the entrance to Versailles would have certainly far surpassed any other of de Chirico’s experiences of an enormous, little-populated public space, whether in Paris or in Italy.

The description coincides in several telling ways with the painter’s well-known “revelation of the enigma” of 1912, which has often been cited as a rare insight into his working method.

... let me recount how I had the revelation of a picture that I will show this year at the Salon d’Automne, entitled Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon. One clear autumnal afternoon I was sitting on a bench in the middle of the Piazza Santa Croce in Florence. It was of course not the first time I had seen this square. I had just come out of a long and painful intestinal illness, and I was in a nearly morbid state of sensitivity. The whole world, down to the marble of the buildings and the fountains, seemed to me to be convalescent. In the square rises a statue of Dante draped in a long cloak, holding his works clasped against his body, his laurel-crowned head bent thoughtfully earthward. The statue is in white marble, but time has given it a gray cast, very agreeable to the eye. The autumn sun, warm and unloving, lit the statue and the church facade. Then I had the strange impression that I was looking at all these things for the first time, and the composition of my picture came to my mind’s eye. Now each time I look at this painting I again see that moment. Nevertheless, the moment is an enigma to me, for it is inexplicable. And I like also to call the work which sprang from it an enigma. (Soby, 1955, p. 251)8

The first parallel between the two accounts is the anthropomorphizing of architecture. In the Versailles passage, things looked at the painter. The various aspects of architecture, “every angle of the palace, every column,” and most notably the window, “had a soul.” In the Florence experience in the Piazza Santa Croce, even the “marble of the buildings and the fountains seemed to me to be convalescent,” as was the painter. Then, in both, the sun is shining but is either “unloving” or “without love” (which de Chirico emphasizes in italics in his description of Versailles). The Florentine experience is see...