- 402 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Oceanography

About this book

The second edition of Environmental Oceanography is the first textbook to link the needs of the coastal oceanographer and the environmental practitioner. The ever-increasing human impact on the environment, and particularly on the coastal zone, has led governments to carefully examine the environmental implications of development proposals. This book provides the background needed to undertake coastal oceanographic investigations and sets them in context by incorporating case studies and sample problems based on the author's experience as an environmental consultant.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 | Coastal Oceanography |

“Begin at the beginning,” the King said gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Oceanography — or oceanology, as the Chinese and Russians prefer to call it — is the scientific study of the deep and coastal waters of our planet. It traditionally consists of four branches: physical oceanography, chemical oceanography, biological oceanography, and geological oceanography. The knowledge gained through this fascinating and challenging field of science can be used by society to improve its fishing industry, assist maritime transport, exploit offshore resources, develop alternate ocean-based sources of energy, and strengthen naval defences. The oceanographic knowledge that is required by these areas comprises maritime oceanography.

The sea joins the land, and oceanography therefore has a terrestrial aspect to it. The two major concerns here are, first, the provision of recreation facilities to those of the population who wish to use the shoreline, and, second, the prevention of pollution to preserve the harmony of marine biological life. The oceanographic knowledge that is required by these areas comprises environmental oceanography.

Of course, maritime oceanography and environmental oceanography overlap. Maritime transport requires the provision of ports and harbours. Their construction and subsequent dredging may cause problems of pollution because of the large quantities of sediment moved. Conversely, improved knowledge of warm currents — such as the East Australian current or the Gulf Stream — will provide information that is useful to the maritime oceanographer concerned with ship routing as well as to the environmental oceanographer concerned with biological productivity.

This book deals mainly with physical oceanography, which describes the oceans in terms of their physical characteristics and attempts to explain their behaviour in terms of physical mechanisms. In particular, it deals with the interrelation and interaction between physical oceanography and oceanography’s other branches.

Physical oceanography is a fascinating and challenging field of science that may be studied for its own sake. It also provides answers to some of the questions that will be asked during future exploitation of oceanic resources. For example: how important are ocean surface currents in maritime transportation? Do subsurface currents carry industrial waste into unwanted locations? Will ocean waves damage drilling platforms at sea and harm coastal structures on land?

During the past four decades there has been a vast increase in our knowledge and understanding of physical oceanography. Some of this has come from laboratory work and experiments, and some of it has come from data painstakingly collected in the deep oceans of the world, but recently most of it has come from satellite data. For a long time, the excitement, adventure, and discovery involved in deep water oceanography overshadowed coastal and estuarine oceanography. But when renewed interest in man’s nearshore environment surfaced, scientists started to apply their knowledge of physical oceanography to nearshore and estuarine situations. Occasionally, the knowledge was found to be lacking. Coastal waters have an inherent variability that greatly complicates attempts to understand them. Furthermore, the knowledge gained in the ocean, where salinity variations are small, must be applied carefully to the estuarine situation, where the salinity variations may be huge.

Physical oceanography is itself considered to be composed of two parts. Synoptic oceanography refers to the observation, preparation, and interpretation of oceanographic data and is generally the branch of oceanography in which most geographers are interested. Dynamic oceanography applies the already known laws of physics to the ocean, regarding it as a fluid acted upon by forces, and solves the resulting mathematical equations. Of course, neither part can stand alone. The predictions of the dynamic oceanographer need to be tested by the synoptic oceanographer, the results of the synoptician explained by the dynamicist.

This division into synoptic and dynamic parts is also true of meteorology — the study of the atmosphere. There is a close symbiosis between meteorology and oceanography. Both study environmental fluids — a liquid in one case, a gas in the other — and the same mathematical tools can pry at both fields. They are also interconnected. Ocean temperatures affect the atmosphere. Hurricanes are a dramatic example of this, because they can form only if the sea surface temperature can heat the atmosphere sufficiently for air parcels to ascend through the lower atmosphere. In practice, this means that the sea surface temperature must exceed 27°C. But the atmosphere also affects the oceans: winds drive upper layer currents and they determine the nature of the waves generated on the ocean surface. The oceans and the atmosphere are an extremely complicated, mutually interacting system.

There is one important difference between meteorologists and oceanographers. Oceanographers talk of the direction towards which a current is moving, whereas meteorologists refer to the direction from which a wind has come. The meteorologist’s westerly wind will, in the first instance, generate an eastward drift of water.

In this volume we present a physical description of coastal waters and explain in a simplified form some of the dynamic theories believed to control them. The average biologist, chemist, geologist, or environmental scientist when tackling a marine problem may well find that he or she can manage adequately at first with no input from the physical oceanographer. But, as the investigation continues, there will be many vexing physical questions unanswered, and an inadequate knowledge of these can lead to problems. Because of this, most modern coastal oceanographic and estuarine work is carried out by interdisciplinary teams working together. To obtain the best results from these teams, each specialist must be able to communicate sensibly with the other specialists. The aim of this volume is to provide environmental practitioners with the necessary skills to communicate with physical oceanographers and to introduce physical oceanographers to the types of problems that interest the wider community.

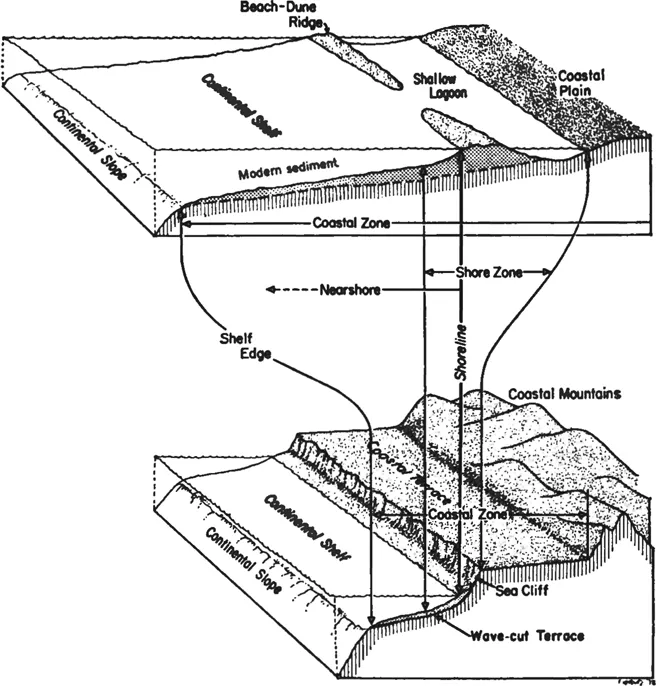

FIGURE 1.1 Typical coastal depth profile showing the names of various geomorphological features. The waters in the depicted region are sometimes called neritic waters. (From D. L. Inman and B.M. Brush, Science, 181, 20–31, 1973. With permission.)

1.2 COASTAL WATERS

What is the coast and what are coastal waters? There are no unique definitions, and the military, political, scientific, and economic uses of the terms differ. In order to cover as broad a scan as possible, this book treats the coast as being synonymous with the coastal zone depicted in Figure 1.1. This extends from the edge of the continental shelf (if there is one) to the limits of geologically recent marine influence. Nevertheless, other definitions and views are important — nations tend to wage war when their coast is invaded — and we shall examine some of them in more detail.

1.2.1 THE COASTAL ZONE

Coastal zone managers need a legal definition to set their jurisdiction. The exact wording will vary from state to state, but one definition of the coastal zone that is in common use (and was adopted by Western Australia) is

The land and waters extending inland for 1 kilometre from high water mark on the foreshore and extending seaward to the 30-metre depth contour line and also including the waters, beds, and banks of all rivers, estuaries, inlets, creeks, bays, or lakes subject to the ebb and flow of the tide.

The concern here is to define the inward extent of coastal waters as much as their outward extent. The overriding consideration is tidal penetration, which here has been defined in terms of movement. It is also possible to examine tidal effects in terms of salt fluctuations. Coastal waters extend inland as far as do tidal effects; estuaries and deltaic river mouths can be thought of as comprising coastal waters. Notice that our working definition is broader than the legal one given above. Our seaward limit extends to the continental shelf slope (explained more fully later) which may be deeper than 30 m. Similarly, the landward extent of recent marine influence may be greater than 1 km.

1.2.2 THE CONTINENTAL SHELF

The continental shelf refers to a physical concept and also nowadays to a legal concept. The physical concept is that of the seaward prolongation of the continental land mass. The enormous number of measurements made around the world’s continental margins have led to a composite picture of the average continental shelf. This mythical entity consists of a shelf 65 km wide which descends at a gradient of 1 in 500 (or 0°7′) to a water depth of 128 m at its outer edge. The continental shelf terminates at the shelf break, which is the point at which the gradient increases to 1 in 20, and seaward of the break lies the continental slope.

Unfortunately for the legal concept of the continental shelf, the distance over which the continental shelf will stretch from the coast varies considerably. In some places, a well-defined continental shelf does not exist. Problem 1.3 at the end of this chapter illustrates that some Pacific Islands are virtually mountains poking out of the deep sea. Elsewhere the shelf may stretch for several hundred kilometres — as it does off the northwest coast of Australia.

This book focuses attention mainly on the waters of the continental shelf, known to biologists as the neritic waters. There are occasions when coastal nations consider their coastal waters to comprise the waters above their continental shelf and their continental slope; this extended boundary is called the continental margin. Lawyers involved with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)* experimented with a number of alternative definitions for it. These included:

1. A line fixed 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the coast

2. The 500-m depth contour, known as the 500-m isobath

3. A line at the foot of the continental slope

Their final decision may be found ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1. Coastal Oceanography

- Chapter 2. Shore Processes

- Chapter 3. Waves

- Chapter 4. Tides

- Chapter 5. Water Composition

- Chapter 6. Water Circulation

- Chapter 7. Boundary Layers

- Chapter 8. Mixing

- Chapter 9. Coastal Meteorology

- Chapter 10. Estuaries and Reefs

- Chapter 11. Direct and Remote Sensing

- Chapter 12. Data Analysis

- Chapter 13. Coastal Assessment

- Appendix 1. Surfing the Internet and World Wide Web

- Appendix 2. Some Physical Quantities in SI Units

- Appendix 3. Sample Equipment List

- Appendix 4. Wave Glossary

- Appendix 5. Oceanographic Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Environmental Oceanography by Tom Beer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.