![]()

1 Introduction and overview

1.1 Setting the scene

There have been many significant changes in the construction sector within the past decade. Notably, the sector has witnessed the growth of partnering and alliancing which require better management of the supply chain, and an increasing use of the NEC Contract (NEC3) which requires a team-based proactive approach to project delivery.

New financial models have been developed including Private Finance Initiative (PFI), Local Asset Backed Vehicles (LABVs) and variants of these in which private sector consortia design, build, own and operate public facilities in partnership with the public sector. Great advances have been made on the technical front with the growth of Building Information Modelling (BIM) and other web or cloud-based project management platforms. Enlightened clients have also been demanding more sustainable developments and construction projects.

Yet the same fundamentals apply – clients wish to obtain their increasingly more complex projects within budget and on time and to the necessary quality. Cost management, a function traditionally undertaken by quantity surveyors, therefore remains of critical importance to project success. One of the pioneer quantity surveyor construction project managers was Francis Graves who undertook the task of Project Controller in 1972 on the massive 5-year-long Birmingham NEC Exhibition Centre project. He considered his terms of reference on this project very straightforward – Get it finished on time and get value for money! This maxim still resonates today and forms the core of the services offered by all quantity surveying firms on construction and engineering projects.

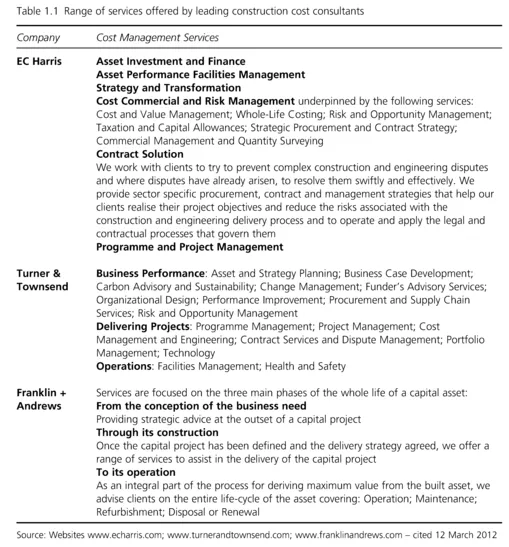

It is significant to observe however that the practice of cost management and the role of the quantity surveyor is changing in response to all the pressures highlighted above. Indeed, many are moving on from the core skills of contractual and financial management to embrace the key role of the client’s strategic adviser and project manager. Evidence of this development can be seen from an analysis of three of the top Quantity Surveying Consultants’ websites which shows their involvement in a wide range of strategic services which are increasingly being offered throughout the life of the asset (Table 1.1).

It is within this context that this book is written to map out some of the key principles and techniques that underpin cost management practice and signpost some of the critical developments in the construction sector that will continue to shape the future role of the cost manager.’

1.2 Construction overview

The construction sector is strategically important for Europe, providing the infrastructure and buildings on which all sectors of the economy depend. With almost 20 million operatives directly employed in the sector, it is Europe’s largest industrial employer accounting for 7 per cent of total employment and 28 per cent of industrial employment in the European Union (EU). It is estimated that 44 million workers in the EU depend in one way or another on the construction sector. Construction contributes more than 10 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) and more than 50 per cent of the gross fixed capital formation of the EU, representing about €1.36 trillion in 2011 (Europa).

The industry continues to thrive, given the ever-pressing need to address the regeneration of many urban areas of Europe, in particular in the newly acceded countries and the realization of major trans-European infrastructure works.

Being a subset of the wider EU market, the UK construction industry similarly makes a considerable contribution to the national economy, accounting for over 7 per cent of the national gross domestic product. Just over 2.14 million workers work in construction. In 2011 the construction sector represented £110 billion of expenditure – 40 per cent being in the public sector, with Central Government being the industry’s biggest customer.

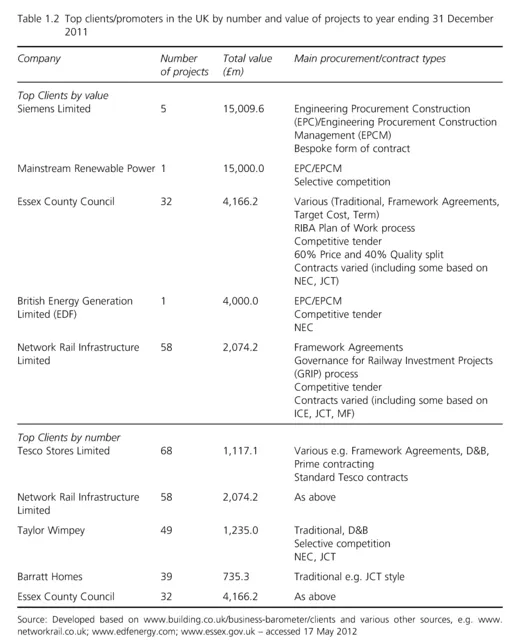

Other major clients/promoters by value and number of projects procured are shown in Table 1.2. Significantly, these major clients have shown the lead in embracing the new procurement routes and conditions of contract. What they all seek is value for money and it is within this context that cost management, and the role of the cost manager, takes significance.

1.3 Cost management in construction

Cost management in construction and the role of the quantity surveyor in delivering these services has developed significantly and continues to evolve to meet the changing needs of clients. This evolution has been driven in part by the impetus for change in procurement and contract strategies generated by the numerous reports on the state of the UK construction industry published in the last 70 years (see Murray and Langford, 2003). These reports and other relevant key recommendations are reviewed in Chapter 2 in order that best practice, which needs to be reflected in the role of quantity surveyors, can be identified.

Beyond these, the role of the quantity surveyor also continues to be influenced by the requirements of professional bodies. For instance the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors’ (RICS) Assessment of Professional Competence/Assessment of Technical Competence (RICS, 2006) identifies that quantity surveyors may be working as a consultant in private practice, for a developer or in the development arm of a major organization (e.g. retailer, manufacturer, utility company or airport), for a public sector body or for a loss adjuster. On the contracting side, quantity surveyors could be working for a major national or international contractor, or local or regional general contractor, for a specialist contractor or subcontractor, or for a management-style contractor. It identifies the need for competence in:

- preparing feasibility studies or development appraisals

- assessing capital and revenue expenditure over the whole life of a facility

- advising clients on ways of procuring the project

- advising on the setting of budgets

- monitoring design development against planned expenditure

- conducting value management and engineering exercises

- managing and analysing risk

- managing the tendering process

- preparing contractual documentation

- controlling cost during the construction process

- managing the commercial success of a project for a contractor

- valuing construction work for interim payments, valuing change, assessing or compiling claims for loss and expense and agreeing final accounts

- negotiating with interested parties

- giving advice on the avoidance and settlement of disputes.

These guidelines for the RICS Assessment of Professional Competence in Quantity Surveying and Construction were issued in July 2006 (Isurv.com).

Similarly, professional bodies like the Construction Industry Council (representing all the professions), the Association of Project Management, the Major Projects Association and the Chartered Institute of Building all identify key skills and competencies applicable to modern day quantity surveyors, which are constantly under review.

It is evident from the foregoing that not only is cost or commercial management critical to achieving value-for-money outcomes but also that the requirements for effective performance of this role are constantly evolving. This inevitably necessitates constant review and evaluation of cost or commercial management practice to ensure that both industry and academia keep pace with these changes and with best practice.

1.4 Learning from case studies

A few examples will suffice to illustrate the role that case studies play in identifying best practice (and indeed bad practice), thereby providing learning opportunities from both successful and failed projects which will provide the basis for delivering best value to clients through the effective performance of cost management services. Indeed, very often the distinction between successful and failed projects is blurred.

Many of the 1970s UK North Sea oil projects went way over budget, yet, following the subsequent surge in oil prices, were clearly successful projects. The Thames Barrier at Greenwich was a project plagued by poor industrial relations, finishing 3 years late in 1984 and at ten times the original budget, yet, when the barrier was later used, the innovative designed project was successful and London was saved from flooding. Today the barrier is raised six times per year compared to once in 6 years as originally anticipated. Clearly there are important lessons to be learnt from all projects.

The Sydney Opera House in Australia became the symbol for the Millennium Olympics in 2000 and somehow reflected the healthy swagger of the emerging continent. The competition for the project was won in 1957 by Danish architect Jorn Utzon, whose first design according to members of the jury was hardly more than a few splendid line drawings. This comment could also have been made many years later in connection with Enric Miralles’ first submission on the Scottish Parliament building.

The billowing concrete sailed roof had never been built before. It should therefore have been no surprise that the $A7 million project escalated to over $100 million and the planned construction period of 5 years was finally extended to 14 years (1959–1973). The architect was put under so much pressure over the escalating costs that he left the project half-way through, after which his designs were modified. As a result, the building is perfect for rock concerts but not suitable for staging classical full-scale operas (Reichold and Graf, 1999).

Another iconic building is the Pompidou Centre in Paris, a building famous for being inside-out with all the structural frame, service ducts and escalators being on the outside, allowing a flexible floor space within. The audacious steel and glass National Centre for Art and Culture was designed by two young unknown architects, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, to last, as George Pompidou reminded architects, for four or five centuries.

After opening in 1977 the centre rapidly became a huge success, with more than 7 million visitors a year making it the most popular tourist destination in Paris. After 20 years’ use the building was showing its age, including rusting on the structural frame, and was in need of a major renovation. In October 1997 the whole centre closed, reopening in January 2000, which allowed not only for the refurbishment but also for improvements to the internal layout at an estimated cost of US$100 million (Poderas, 2002).

Significantly the UK Government now requires whole-life costing to be considered with project evaluation. It is interesting to speculate as to whether the Pompidou Centre would have passed such a test if the building were proposed to be built in the UK today.

The Millennium Dome at Greenwich was designed to be the UK’s showcase to celebrate the new millennium. With ...