Introduction

Exercise scientists joke (although there is a hint of truth in everything we say) that to succeed in sport you are well advised to choose your parents carefully. Each individual is significantly influenced by their own genetic make-up (genotype), as well as by environmental factors such as living conditions during growth and development – genotype plus environmental factors produces our phenotype.

In this chapter we will first consider where sciences such as human anatomy and physiology of exercise fit in the bigger picture of life, the universe and everything. The biology of exercise resides in the domain of the life sciences, which encompasses a diverse range of scientific fields such as psychology, medicine, marine biology and environmental biology. How might our pursuit of an increasing knowledge and practice base in human anatomy and the physiology of exercise relate to other branches of the life sciences?

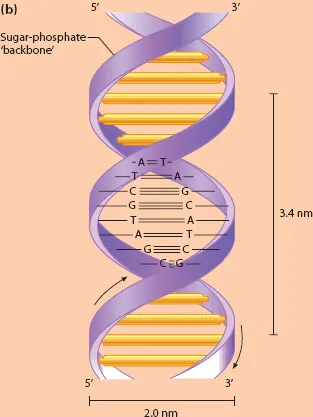

We can celebrate two important events at the forefront of endeavour in sport and exercise, and in science that occurred around 60 years ago. These were the feats of reaching the highest point on earth (Everest) for the first time and the discovery of the double helical structure of DNA (Figure 1.1) and, thus, the first precisely defined amino acid sequence of a protein.

Reaching the top of Sagarmartha (the Nepalese name for Mount Everest) cannot be achieved without considerable physiological, psychological and biomechanical endurance. Whilst not being technically difficult to climb, it requires the support of a highly skilled team, including members trained in the life sciences. Multi-tasking and multidisciplinarity are fundamental for any expeditionary and scientific team. The environment is extreme, and respect for this and for the people, flora and fauna and the health economy of the Himalaya are important factors. The support of the indigenous people is also essential. They are genetically adapted, both physiologically and psychologically, to survival at higher altitudes. This is exemplified by the new record set in 2004 by the 26-yearold Sherpa, Pemba Dorjee, who reached the summit of Everest, from base camp, in just over eight hours, a journey that is normally scheduled over four days, with overnight recovery periods.

Modern day teams of Western climbers need to include medical, paramedical, physiological, nutritional and psychological support in order to achieve success. The physiologist on the 1953 Everest Expedition was Griffith Pugh, who had accompanied Eric Shipton to the Himalaya in 1952 and wrote a report from which a number of useful lessons could be learnt. In his account of the ascent, Hunt (1953) notes ‘This climbing party was further enlarged by the attachment of two others . . . . The first was Griffith Pugh, a physiologist employed in the Division of Human Physiology of the M.R.C., who had a long experience of what may be termed mountain physiology.’ There was considerable discussion about including ‘members whose objectives are different from those of the rest of the team. But there was no denying the contribution made by a study of physiology to the problem of Everest in the past’. One of Pugh’s roles was to look after food and diet for the expedition. The sport and exercise scientist can perform a key role in such a team and must be able to participate fully and understand where everyone ‘is coming from’. The ultimate team is greater than the sum of its component parts and the team effect is to add value, to provide a platform for individuals to excel. At the same time it must be remembered that such individuals are impotent without the support of the other team members.

Fig. 1.1 Two important events of 1953: (a) the ascent of Everest and (b) the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA.

The ascent of Everest can be compared with other sport and exercise pinnacles, such as becoming the fastest person in the world on the track or in the pool, or in a dinghy, kayak or rowing boat. Again, nearly 60 years ago (in 1954), the mile was run by Roger Bannister in less than 4 minutes for the first time. In 2012 the record stands at around 3 minutes 43 seconds (Hicham El Guerrouj, in 1999). In 1952, the world record for the marathon of 2 hours and 25 minutes (Yun Bok Suh, Korea, in the 1947 Boston Marathon, having been knocked to the ground by a dog, suffering a serious gash and broken shoelace) was broken by James Peters in 2 hours and 20 minutes, despite him being hit by a car 8 miles into the race! Women were not even ‘allowed’ to run such a distance competitively. Now the marathon has been run in less than 2 hours and 4 minutes (Kenyan, Patrick Macau Musyoki in Berlin, 2011) at an average speed just over 20 km/hour, and Paula Radcliffe holds the women’s world record time of 2:15:25 set in 2003. An interesting account of the fight to establish the women’s Olympic marathon race can be found in Lovett (1997). People now speculate when, not if, the marathon will be run in less than 2 hours – requiring an average speed of just over 21 km/hour. A current estimate is that this will be achieved by 2028.

These are achievements and challenges of a sporting nature, but equally important challenges and other dimensions for exercise biology in the twenty-first century can be found in the field of medicine. The epidemics of modern diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity and cancer, are a threat. Knowledge of these medical conditions, prevalent in industrialized countries are an opportunity for exercise biologists to shape the future of human morbidity and mortality through a greater dependence on primary prevention. The relative importance of this was described as the need to wage war on modern chronic diseases (Booth et al., 2000).

Previous U.K. government health policies called National Service Frameworks (see the section ‘Health’ in Chapter 6) set out targets for the prevention and control of such diseases. Related to this is the opportunity to relate and apply functional exercise biology to the genomic potential (and susceptibility) of an individual through newfound knowledge of the human genome.

This is the context for this chapter, briefly introducing the key features of molecular biology and the chemistry of life that sport and exercise scientists might contemplate in order to take a holistic approach to the subject as it sits in the life sciences. So let us begin with the exciting human genome revelations of our time.

Sixty years ago the first protein amino acid sequence was defined and the double helical structure of DNA was explained; both were exciting landmarks in science. In 1996 the first ever DNA sequence of a eukaryotic organism (a yeast) was completed, and in 1990 an international project – the Human Genome Project (HGP) – began to map and sequence the whole of the human genome. The working draft sequence of the human genome was published in 2001 and in the subsequent years final touches were made to the sequences and map of the human genome. This is quite simply what it is – a map. Maps are of little use unless they can be interpreted and used to their maximum potential. Enter the navigator – the physiologist!...