- 108 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Offering a series of well-defined problems supplemented by solutions, Exercises in Practical Astronomy: Using Photographs presents meaningful practical work in elementary astronomy and astrophysics. The book provides authentic astronomical photographs of very high quality on which different types of objects can be studied with equipment as simple as rulers and protractors. In addition to photographs and a set of exercises that cover 12 topics, the coverage includes ample hints and worked solutions that are designed to enable students to work independently. SI units are used for physical data and in conversions of astronomical quantities. This book is one of the few to use real rather than idealized or simplified data in the problems.

Information

Topic

Scienze fisicheSubtopic

Astronomia e astrofisica1 The Sun

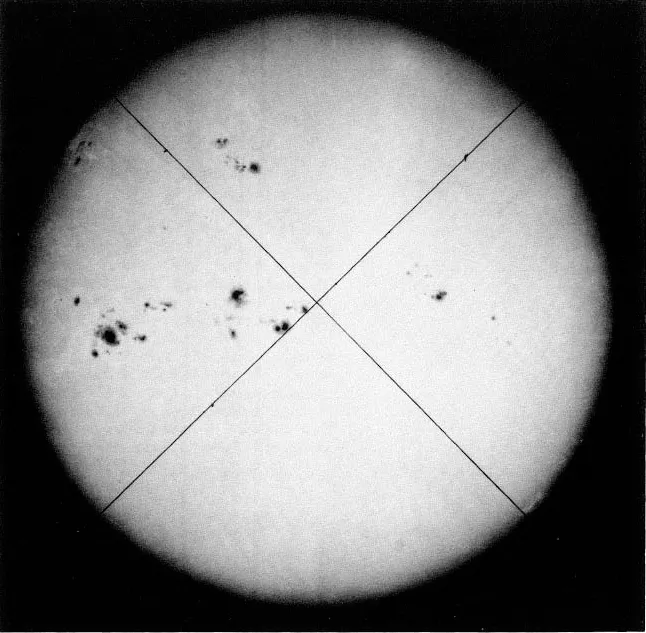

The Sun, our nearest star, is 1.5 × 1011 m from Earth. This distance, called the astronomical unit (AU), is one of the units used in astronomy, especially for distances inside the Solar System. The Sun has a radius of 7.0 × 108 m. The bright disk which we see in the sky (plate 1.1) is called the photosphere or light sphere. A conspicuous feature of the photosphere is the decrease in its surface brightness from the centre to the edge or limb of the disk, a phenomenon known as limb darkening, which is a result of the gaseous nature of the photosphere whose temperature varies with depth. Dark sunspots of various sizes are another feature; they are temporary phenomena which reach a maximum in numbers approximately every 11 years.

Plate 1.1 The Sun showing limb darkening and a number of sunspots (© Royal Greenwich Observatory and Royal Observatory, Edinburgh).

THE ROTATION OF THE SUN

The rotation of the Sun was first recognised from the movement of sunspots across its disk. The series of photographs (plate 1.2) taken over a period of time illustrates this clearly. If a particular spot persists for more than a complete rotation, the interval between two successive occasions when it is exactly on the central meridian (the diameter joining the Sun’s poles on its projected image) is the period of rotation. However, it is possible to work out the period without following a spot through a whole cycle—indeed the lifetime of all but the largest spots is less than a cycle. The period observed in this way is the synodic period, that is, the period as seen from the Earth. Since the Earth is in motion around the Sun this period differs from the true or sidereal period which is that which would be observed from a stationary place in outer space.

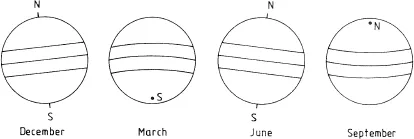

The Sun’s axis of rotation fixes its poles and its equator. Latitude on the Sun, as on the Earth, is measured from the equator. Longitude on the Sun is measured for convenience from the central meridian, though of course this meridian changes continuously as the Sun rotates. The plane of the Sun’s equator is tilted at a small angle (7°) to the ecliptic, the plane of the Earth’s orbit. As a result the Sun’s axis of rotation is not normally in the plane of the sky. One of the poles is likely to be behind the visible disk at any moment. The Sun’s axis of rotation is likewise not normally perpendicular to the ecliptic (figure 1.1).

The plane of the ecliptic is inclined at an angle of 23.4° to the plane of the Earth’s equator; the angle which the axis of the ecliptic makes with the north–south direction in the sky varies therefore with the time of year. The actual angle between the axis of rotation of the Sun and the north–south direction in the sky (called the position angle of the Sun’s pole) is a combination of the effect of the 23.4° inclination of the ecliptic and of the 7° inclination of the Sun’s axis. The angle is calculated for every day in the year and published in advance in tables. It is easily observed from the apparent path of sunspots across the face of the Sun.

Sunspots are found in belts of solar latitude between 5° and 30° in both hemispheres. The path of a spot around the Sun’s axis therefore follows a small circle of solar latitude. When the Sun’s axis of rotation is exactly in the plane of the sky (in December and June, figure 1.1) the projection of the small circle is a straight line. At other times the apparent path is slightly curved, but for simplicity in calculation we assume that the shape of a small circle is not very different from a straight line.

The photographs (plate 1.2) are taken from the famous Greenwich daily photographic records of the Sun, begun in 1874 and continued for over a century. The particular set reproduced here belongs to the high sunspot maximum of 1948 and shows an unusually large number of spots and groups of spots. The orientation of the sky is indicated on all the photographs by lines produced by a pair of crossed threads in the focal plane of the instrument. The north (which is at the top) is found by bisecting the angle between the cross-lines, though the intersection of the lines may not necessarily coincide with the centre of the Sun’s image.

Figure 1.1 Aspects of the Sun in the course of the year.

Exercise 1. Find the Sun’s axis of rotation from the movement of sunspots across the disk.

Suggestions. Study the photographs and choose a spot whose motion can be followed over several days. The exercise may be repeated later using other spots, but it is advisable not to try to keep track of more than one spot at a time. Draw a circle on an overlay which has the same diameter as the Sun’s image and mark on it a north–south diameter and also the centre of the circle. On each image bisect the angle between the crossed lines (by the use of a protractor) and draw a line parallel to this direction through the centre of the image. Place the overlay on the images successively, keeping the north–south line fixed, and trace the chosen spot. The tilt of the Sun’s axis to the plane of the sky is so small (4° in the month of May) that the path of the spot is virtually a straight line. When these points are joined they mark the chord on which the particular spot moves. A line perpendicular to this through the centre of the circle marks the Sun’s central meridian which should turn out to be the same whichever spot you use.

THE SUN’S SIDEREAL AND SYNODIC PERIODS

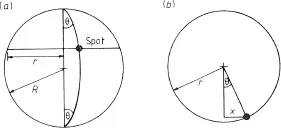

Figure 1.2(a) is a diagram showing the apparent path of a spot across the Sun’s disk, which is a chord of the disk. The true path of the spot is a circle as shown in figure 1.2(b). The radius r of this circle is smaller than the Sun’s radius R because the spot is not on the Sun’s equator. If the spot is at longitude θ, the observer on Earth sees the spot at a projected distance r sin θ (marked x on the diagram) from the central meridian. If r and r sin θ are observed, the angle θ (its longitude) may be calculated for each date. The rate at which the longitude θ increases is the rate of the Sun’s synodic rotation, and the time which the spot would take to travel 360° is the synodic period.

Figure 1.2 (a) Path of a sunspot on a chord of radius r. The sunspot is at longitude θ from the central meridian. (b) Cross-section through the Sun showing the circle on which the sunspot moves. The spot is seen at a projected distance x from the central meridian.

Figure 1.3 is a diagram in the plane of the ecliptic showing a cross-section of the Sun and also the orbit of the Earth. The directions of rotation of the Sun on its axis and of the Earth’s motion around the Sun are shown. The Earth is at position 1 when a sunspot is seen on the central meridian at position A. After the Sun has performed a full rotation on its axis the spot has returned to position A but the Earth has moved on. The Sun has to rotate a little further until the spot appears when observed from the Earth to be once more on the central meridian. The Earth is now at position 2 and the sunspot at position B. The time it takes for the Sun to return to A is the sidereal period, which is the true period of rotation. The time it takes for the Sun to move from A back to A and on to B is the synodic period, in which it appears t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- To the Teacher

- To the Student

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Sun

- 2. Minor Planets or Asteroids

- 3. Halley’s Comet

- 4. The Milky Way

- 5. Stars in Motion

- 6. Open Star Clusters

- 7. Globular Star Clusters

- 8. Interstellar Extinction

- 9. A Supernova and Supernova Remnants

- 10. Types of Galaxies

- 11. Nearby Galaxies

- 12. Clusters of Galaxies

- Appendix 1. Astronomical Definitions, Data and Conversions

- Appendix 2. Magnitudes, Colours and Luminosities

- Appendix 3. Sources and References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Exercises in Practical Astronomy by M.T Buck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze fisiche & Astronomia e astrofisica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.