- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Chicana Feminist Thought brings together the voices of Chicana poets, writers, and activists who reflect upon the Chicana Feminist Movement that began in the late 1960s. With energy and passion, this anthology of writings documents the personal and collective political struggles of Chicana feminists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Chicana Feminist Thought by Alma M. Garcia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Études relatives au genre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Sciences socialesSubtopic

Études relatives au genreI

VOICES OF CHICANA FEMINISTS: AN EMERGING CONSCIOUSNESS

Introduction

First surfacing as Chicana nationalists and perhaps influenced by strong female role models within their own families, some Chicanas by the early 1970s began to seriously question the very cultural nationalism—Chicanismo—that had first engaged them in the movement. Their critique was based on their experiences and observations within the movement which suggested to them certain contradictions in Chicano nationalism as it related to gender issues. The glorification and romanticization, for example, of the Chicano family and the traditional role of women within the family by the movement appeared to these Chicanas to maintain women as second-class citizens of El Movimiento.

As a result, emerging Chicana feminists initiated a critique of the very concept of the Chicano family and of the traditional role of women within Mexican-based culture. The following essays in this section illustrate this dialogue among Chicana feminists concerning the need to question particular family and cultural traditions including the role of the Catholic Church steeped in patriarchy and sexism. Such traditions, Chicana feminists asserted, contradicted the movement’s stress on freedom and liberation. Who was to be freed and liberated? Only men?

Yet while Chicana feminists challenged some of the very cultural traditions that the Chicano movement was extolling, they did not in a blanket fashion condemn all traditions nor did they place all of the burden of their oppression on male domination. Chicana feminists, for example, observed that within the very culture that they were critiquing was to be found the inspiration for their own cause. As Anna Nieto-Gómez noted in her essay in this section, contrary to the stereotype of the passive Mexican woman, history revealed strong female role models who represented the origins of Chicana feminism. Expanding Chicano nationalism to include the role of assertive and strong Chicanas, Chicana feminists recognized that their questioning of their own culture represented only one aspect of their struggle. They stressed that besides the internal gender wars that they had to engage in, that they at the same time had to join Chicano males in their common struggle against race and class oppression.

The following essays document the difficult and sensitive efforts by Chicana feminists to challenge the essentialism of the movement and at the same time mobilize their opposition by staying within their own cultural boundaries.

La Nueva Chicana (1971)

The old woman going to pray

does her part,

The young mother hers,

The old man sitting on the porch,

The young husband going to work,

But let’s not forget the young

Chicana,

Bareheaded girl fighting for equality,

Unshawled girl living for a better world,

Let’s not forget her,

Because,

She is LA NUEVA CHICANA

Wherever you turn,

Wherever you look,

You’ll see her,

She’s still the soft brown-eyed

beauty you knew,

There’s just one difference,

A big difference,

She’s on the go spreading the word.

VIVA LA RAZA

Is her main goal too,

She is no longer the silent one,

Because she has cast off the

shawl of the past to show her face,

She is LA NUEVA CHICANA

Ana Montes

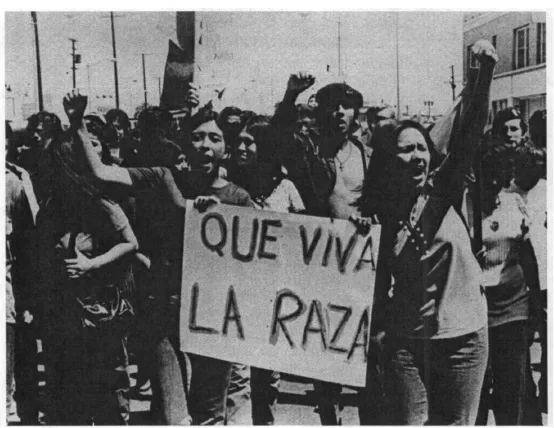

Protest march in Los Angeles, California, early 1970s. Courtesy of Raul Ruiz, La Raza magazine, Los Angeles, California.

1

New Voice of La Raza:

Chicanas Speak Out*

At the end of May [1971], more than 600 Chicanas met in Houston, Texas, to hold the first national conference of Raza women. For those of us who were there it was clear that this conference was not just another national gathering of the Chicano movement.

Chicanas came from all parts of the country inspired by the prospect of discussing the issues that have long been on their minds and which we now see not as individual problems but as an important and integral part of a movement for liberation.

The resolutions coming out of the two largest workshops—”sex and the Chicana” and “marriage—Chicana style”—called for “free, legal abortions and birth control for the Chicano community; controlled by Chicanas.” As Chicanas, the resolution stated, “we have a right to control our own bodies.” The resolutions also called for “24-hour childcare centers in Chicano communities” and explained that there is a critical need for these since “Chicana motherhood should not preclude educational, political, social and economic advancement.”

While these resolutions articulated the most pressing needs of Chicanas today, the conference as a whole reflected a rising consciousness of the Chicana about her special oppression in this society.

With their growing involvement in the struggle for Chicano liberation and the emergence of the feminist movement, Chicanas are beginning to challenge every social institution which contributes to and is responsible for their oppression, from inequality on the job to their role in the home. They are questioning “machismo,” discrimination in education, the double standard, the role of the Catholic Church, and all the backward ideology designed to keep women subjugated.

This growing awareness was illustrated by a survey taken at the Houston conference. Reporting on this survey, an article in the Los Angeles magazine Regeneración states: “84% felt that they were not encouraged to seek professional careers and that higher education is not considered important for Mexican women…. 84% agreed that women do not receive equal pay for equal work.” The article continues: “On one question they were unanimous. When asked: Are married women and mothers who attend school expected to also do the housework, be responsible for childcare, cook and do the laundry while going to school, 100% said yes. 88% agreed that a social double standard exists.” The women were also asked if they felt that there was discrimination toward them within La Raza: 72% said yes, none said no and 28% voiced no opinion.

While polls are a good indicator of the thoughts and feelings of any given group of people, an even more significant measure is what they are actually doing. The impressive accomplishments of Chicanas in the last few months alone are a clear sign that Chicanas will not only play a leading role in fighting for the liberation of La Raza, but will also be consistent fighters against their own oppression as Chicanas around their own specific demands and through their own Chicana organizations.

Last year, the women in MAPA (Mexican-American Political Association) formed a caucus at their annual convention. A workshop on women was also held at a Latino Conference in Wisconsin last year. All three Chicano Youth Liberation Conferences—held in 1969, 1970, and 1971 in Denver, Colorado—have had women’s workshops.

In May of this year, women participating at a Statewide Boycott Conference called by the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee in Castroville, Texas, formed a caucus and addressed the conference, warning men that sexist attitudes and opposition to women’s rights can divide the farmworker’s struggle. Also in May, Chicanas in Los Angeles organized a regional conference attended by some 250 Chicanas, in preparation for the Houston conference and to raise funds to send representatives from the Los Angeles area.

Another gathering held last year by the Mexican-American National Issues Conference in Sacramento, California, included a women’s workshop which voted at that time to become the Comisión Femenil Mexicana (Mexican Feminine Commission) and function as an independent organization affiliated to the Mexican-American National Issues Conference. They adopted a resolution which read in part. “The effort of Chicana/Mexican women in the Chicano movement is generally obscured because women are not accepted as community leaders either by the Chicano movement or by the Anglo establishment.”1

In Pharr, Texas, women have organized pickets and demonstrations to protest police brutality and to demand the ousting of the city’s mayor. And even in Crystal City, Texas, where La Raza Unida Party has won major victories women have had to organize on their own for the right to be heard. While the men constituted the decision-making body of Ciudadanos Unidos (United Citizens)—the organization of the Chicano community of Crystal City—the women were organized into a women’s auxiliary-Ciudadanas Unidas. Not satisfied with this role, the women got together, stormed into one of the meetings and demanded to be recognized as members on an equal basis. Although the vote was close, the women won.

The numerous articles and publications that have appeared recently on la Chicana are another important sign of the rising consciousness of Chicanas. Among the most outstanding of these are a special section in El Grito del Norte, an entire issue dedicated to and written by Chicanas published by Regeneración and a regular Chicana feminist newspaper put out by Las Hijas de Cuauhtémoc in Long Beach, California. This last group and their newspaper are named after the feminist organization of Mexican women who fought for emancipation during the suffragist period in the early part of this century.

These facts, which are by no means exhaustive of what Chicanas have done in this last period, are plainly contradictory to the statement made by women participating in the 1969 Denver Youth Conference. At that time a workshop held to discuss the role of women in the movement came back to report to the conference: “It was the consensus of the group that the Chicana woman does not want to be liberated.” Although there are still those who maintain that Chicanas not only do not want to be liberated, but do not need to be liberated, Chicanas themselves have decisively rejected that attitude through their actions.

“Machismo”

In part, this awakening of Chicana consciousness has been prompted by the “machismo” she encounters in the movement. It is adequately described by one Chicana, in an article entitled “Macho Attitudes,” in which she says:

When a freshman male comes to MEChA [Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán—a Chicano student organization in California] he is approached and welcomed. He is taught by observation that the Chicanas are only useful in areas of clerical and sexual activities. When something must be done there is always a Chicana there to do the work. “It is her place and duty to stand behind and back up her Macho!”…. Another aspect of the MACHO attitude is their lack of respect for Chicanas. They play their games, plotting girl against girl for their own benefit…. They use the movement and Chicanismo to take her to bed. And when she refuses, she is a vendida [sell-out] because she is not looking after the welfare of her men.2

This behavior, typical of Chicano men, is a serious obstacle to women anxious to play a role in the struggle for Chicano liberation.

The oppression suffered by Chicanas is different from that suffered by most women in this country. Because Chicanas are part of an oppressed nationality, they are subjected to the racism practiced against La Raza. Since the overwhelming majority of Chicanos are workers, Chicanas are also victims of the exploitation of the working class. But in addition, Chicanas, along with the rest of women, are relegated to an inferior position because of their sex. Thus, Raza women suffer a triple form of oppression: as members of an oppressed nationality, as workers, and as women. Chicanas have no trouble understanding this. At the Houston conference 84 percent of the women surveyed felt that “there is a distinction between the problems of the Chicana and those of other women.”

On the other hand, they also understand that the struggle now unfolding against the oppression of women is not only relevant to them, but is their struggle. Because sexism and male chauvinism are so deeply rooted in this society, there is a strong tendency, even within the Chicano movement to deny the basic right of Chicanas to organize around their own concrete issues. Instead they are told to stay away from the women’s liberation movement because it is an “Anglo thing.”

One needs only to analyze the origins of male supremacy to expose that position for what it is—a distortion of reality and false. The inferior role of women in society does not date back to the beginning of time. In fact, before the Europeans came to this part of the world women enjoyed a high position of equality with men. The submission of women, along with institutions such as the church and the patriarchy, was imported by the European colonizers, and remains to this day part of Anglo society. Machismo—which, as it is commonly used, translates in English into male chauvinism—is the one thing, if any, which should be labeled an “Anglo thing.”

When Chicano men oppose the efforts of women to move against their oppression, they are actually opposing the struggle of every woman in this country aimed at changing a society in which Chicanos themselves are oppressed. They are saying to 51 percent of this country’s population that we have no right to fight for our liberation.

Moreover, they are denying one half of La Raza this basic right. They are denying Raza women, who are triply oppressed, the right to struggle around their specific, real, and immediate needs.

In essence, they are doing just what the white, male rulers of this country have done. The white male rulers would want Chicanas to accept their oppression precisely because they understand that when Chicanas begin a movement demanding legal abortions, child care, and equal pay for equal work, this movement will pose a real threat to their ability to rule.

Opposition to the struggles of women to break the chains of their oppression is not in the interests of the oppressed but only in the interest of the oppressor. And that is the logic of the arguments of those who say that Chicanas do not want to or need to be liberated.

The struggle for women’s liberation is the Chicana’s struggle, and only a strong independent Chicana movement, as part of the general women’s liberation movement and part of the movement of La Raza, can ensure its success.

NOTES

1. Regeneración, Vol. I, No. 10, 1971, p. 3.

2. Las Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, unnumbered edition, p. 9.

*From International Socialist Review, October, 1971: pp. 7–9, 31–33.

2

La Chicana: Her Role in the Past and Her Search for a New Role in the Future*

Woman’s struggle to become a person in her own right takes on a peculiar note for the Latin woman. If she also happens to be of Mexican descent, her battle seems almost insurmountable, and yet today the sisters are working to develop a strateg...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright Information

- Introduction

- Part I Voices of Chicana Feminists: An Emerging Consciousness

- Part II Core Themes in Chicana Feminist Thought

- Part Three Chicana Feminists Speak: Voicing a New Consciousness

- Index