This book is a study of part of an academic discipline, particularly of changes in its approaches and content. Approaches and content cannot be appreciated fully without understanding context, however, which this chapter provides. To study an academic discipline is to study a miniature society, which has a stratification system, power structures, a set of rewards and sanctions, and a series of bureaucracies, not to mention occasional interpersonal conflicts (some academic, others not). An outsider may perceive academic work as objective, but many subjective decisions must be taken: what to study and how; whether to publish the results; where to publish them and in what form; what to teach; whether to question the work of others publicly, and so on.

Studying an academic discipline involves studying a society within a society; both set the constraints to individual and group activity. Two questions are focused on here: how is academic life organised; and how does that academic work, basically its research, proceed? Use of the term ‘society within a society’ strongly implies that academic life does not proceed independently in its own closed system but rather is open to the influences and commands of the encompassing wider society. A third necessary question, therefore, is: what is the nature of the society which provides the environment for the academic discipline being studied and how do the two interact? Answering these three questions is set within a framework of studying the ways in which academic life is institutionalised. These are the basic material frameworks within which disciplines evolve. Much of this is not particular to human geography, although its relative novelty as a discipline (a theme considered in more detail in Chapter 2) and relatively small size in terms of overall numbers of students and teaching faculty (especially when compared with disciplines like English literature, history or physics, for example) does reflect back on the structure and perhaps reinforces the sense of community/networks. We therefore start with some details about how these, and attendant hierarchies, are configured in all academic life.

Academic life: the occupational structure

Pursuit of an academic discipline in modern society is part of a career, undertaken for financial and other gains; most of its practitioners see their career as a profession, complete with entry rules and behavioural norms. In the initial development of almost all current academic disciplines, some of the innovators were amateurs, perhaps financing their activities from individual wealth. There are virtually no such amateurs now; very few of the research publications in human geography are by other than either a professional academic trained in the discipline or a member of a related discipline with interests in some aspects of geography – indeed, there has been a recent trend for scientists in a number of other disciplines to become increasingly interested in research topics that many professional geographers tend to consider ‘their own’ (see, for example, Bettencourt and West, 2010; Clauset et al., 2009). The profession is not geography, however. Rather, geography is the discipline professed by individuals who probably state their occupation as university teacher, professor or some similar term. Indeed, the great majority of academic geographers are teachers in universities or comparable institutions of higher education; ‘university’ is used here as a generic term. Academic geographers are distinguished from other professional geographers (many of whom are also teachers) by their commitment to all three of the basic canons of a university: to propagate, preserve and advance knowledge. The advancement of knowledge – the conduct of fundamental research and the publication of its original findings – identifies an academic discipline; the nature of its teaching reflects the nature of its research.

The academic career structure

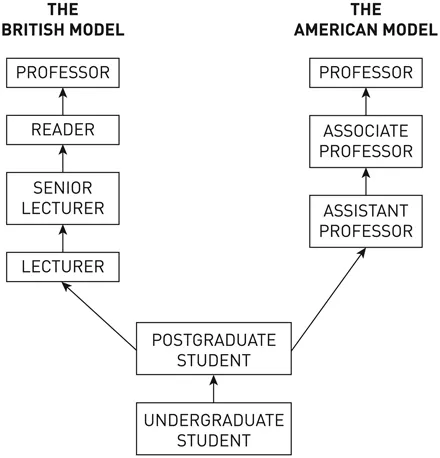

University academic staff members, termed faculty members in North America – hereafter termed academics here – follow their chosen occupation within a well-defined career structure, of which two variants are relevant to this discussion: the British model and the North American model (Figure 1.1), although they have tended to converge in recent years (so the title associate professor is increasingly tending to replace reader and senior lecturer grades in the UK). Entry to both is by the same route. With rare exceptions, the individual must have been a successful student as an undergraduate and, more especially, as a postgraduate. The latter involves pursuing original research, guided by one or more supervisors (in North America, an advisory committee with a chair plays this role) who are expert in the relevant specialised field. The research results are almost invariably presented as a thesis for a research degree (usually the Ph.D.), which is examined by relevant experts; possession of a Ph.D. is now an almost obligatory entrance ticket for both models. Along the way, publication of research findings in specialist journals is expected.

While pursuing the research degree, most postgraduate students obtain experience in teaching undergraduates. Some universities finance many research students through such teaching activities, notably those operating the North American model. The individual may then proceed to further research experience (such as a postdoctoral fellowship or as a research worker on a project directed by a more senior academic), or may gain appointment to a limited-tenure university teaching post, offering an ‘apprenticeship’ in the teaching aspects of the profession while either the research degree is completed or the individual’s research expertise is consolidated.

Beyond these limited-tenure positions lie the permanent teaching posts, which is where the two models deviate. In the British model, the first level of the career structure is the lectureship. For the first years of that appointment (usually three) the lecturer is on probation: training in teaching and related activities is provided (with, increasingly, satisfactory performance on accredited programmes required), annual reports are made on progress as teacher, researcher and administrator, and advice is offered on adaptation to the demands of the profession. At the end of the probationary period, the appointment is either terminated or confirmed.

Figure 1.1 The academic career ladder. Note that whereas in the American model it is very unusual not to progress up through the stages in an orderly sequence, in the British model missing steps is quite common (i.e. some lecturers move direct to readerships, even to professorships, without first being senior lecturers – there are no senior lecturers in the ‘Oxbridge’ universities – and many professors are recruited from the senior lecturer rather than the reader grade). In recent years, many British universities have adopted the terminology of the American model.

Appointment in this model is almost always to a department, which in many cases is named for the discipline which its staff members profess; others may be in a broader school or division – of social sciences, say. The prescribed duties involve undertaking research and such teaching and administration duties as directed by the head of the department, though frequently negotiated through a variety of committees. The lecturers are on a salary scale and receive an annual increment; accelerated promotion may be possible. In the UK there is an ‘efficiency bar’ after a certain number of years’ service; ‘crossing the bar’ involves a promotion, and is determined by an assessment of the lecturer’s research, teaching and administrative activities.

Beyond the lectureship are further grades into which the individual can be promoted. In the universities that were established before the 1990s, the first was the senior lectureship for which there is no allocation to departments but competition across the entire institution. Entry is based again on assessments of the lecturer’s conduct in the three main areas of academic life, and in many universities these include evaluations of research performance and potential from outside experts. (The universities of Oxford and Cambridge are exceptions to this; they do not have a senior lecturer grade, and their salary scale for lecturers is much longer.) The next level is the readership, a position generally reserved for scholars with established research records. The criteria for promotion to it require excellence in research (as demonstrated by their publications and influence) alongside satisfactory performance (at least) on the other criteria. In many universities it is now possible for promotion directly from lectureship to readership. In the post-1990 universities (most of them originally established as polytechnics), the promotional grades were principal and senior lecturer, with readerships only very rarely created. In both, the North American category (see below) of associate professor has increasingly been adopted since the turn of the millennium.

The final grade (associated with academic departments as against administration of the university as a whole) is the professorship. Although superior in status to the others, this may not be a promotional category; until the last few decades most professors were appointed from open competition preceded by public advertisements. Initially, the posts of professor and head of department were synonymous, so a professor was appointed (from a field of applicants after public advertisement) as an administrative head to provide both managerial and academic leadership. With growing departmental sizes and restructurings, however, and the development of specialised subfields within disciplines, each requiring separate leadership, it has become common for departments to have several professors. In most, the headship is a position independent of the professoriate to which other grades may aspire, although many heads are also professors. The post-1990 universities had very few professorships while they were polytechnics, but have since converged with the older universities in terms of these structures. Finally, in the British model, promotion is possible to non-advertised, personal professorships. These positions became increasingly common in the 1990s onwards; in most cases, a personal professorship is awarded for excellence in research and scholarship.

The system under the North American model is simpler. There are three permanent staff (or ‘faculty’ as they are known there) categories: assistant professor, associate professor and professor. The first contains two subcategories – those staff on probation who do not have ‘tenure’ and those with security of tenure. Each category has its own salary range but no automatic annual increments. (In the USA, these scales vary from university to university; the UK has a national salary scale that applies in all universities with only slight local modifications, although individual universities have different scales above the agreed minimum for professors.) Salary adjustments result from personal bargaining based on academic activity in the three areas already listed, and salaries for the three categories may overlap within a department. Movement from one category to another is promotional, as recognition of academic excellence. Professorships are simply the highest promotional grade and do not carry obligatory major administrative tasks. Heads (more usually termed ‘chairs’) of departments in the American model are separately appointed or elected, usually for a limited period only, and they need not be professors (usually referred to as ‘full professors’). Elsewhere in the world, the structures may be some combination of these models, invariably mediated through local norms. And, as we have mentioned, there has also been considerable hybridisation of the original templates in recent years, with a few universities in the UK and elsewhere now referring to those of their academics who would hitherto have been designated as lecturers, senior lecturers or readers as assistant or associate professors.

The nature of academic work

Academic work has three main components: research, teaching and administration (the latter is more often termed ‘service’ by USA-based academics). Entrants to the profession have little or no experience of academic administration and their teaching has probably been as assistants to others. Thus, it is very largely on proven and potential research ability that an aspirant’s initial potential for an academic career is judged, especially in universities that present themselves as ‘research driven’ and where, on average, staff members spend less time on teaching than is the case in other institutions. Research ability can be partly equated with probable teaching and administrative competence, since all require some of the same personal qualities – enthusiasm, organisation, motivation, incisive thinking and ability to communicate orally and in writing: most universities provide appointees with training in teaching and administrative skills. Increasingly, in the British system such formal training has become compulsory and is completed (among many other tasks and much ‘learning by doing’ in the first few years of an academic appointment). To a considerable extent, however, academics gain their first position on faith in their potential (as demonstrated by their letters of application and curricula vitae, references, and their performance at formal and informal evaluation processes, such as interviews and seminars, plus their initial publications), hence the usual probationary periods before tenure is granted.

Once admitted to the profession, academics undertake all three types of work, so that promotional prospects can be more widely assessed. Teaching and administration have traditionally carried less weight with those responsible for promotions than research. This is partly because of perceived difficulties in assessing performance in the first two, and partly because of a general academic ethos which gives prime place to research activity in peer evaluation and wider recognition.

Although not necessarily progressive in terms of increasing level of difficulty, administrative tasks tend to be more complex and demanding of political and personal judgement and skills as the academic becomes more senior, although not necessarily less onerous in terms of time required. A person’s ability to undertake a certain task can often only be fully assessed after appointment or promotion to the relevant position (this has been called the ‘Peter principle’: Peter and Hull, 1969), so decisions must frequently be based on perceived potential; although it is possible to point to somebody whose administrative skills are insubstantial, it is not always easy to assess who will be able to cope with the more demanding tasks.

It has long been argued that assessment of teaching ability is difficult (although clear inability is often very apparent). Student and peer evaluations are increasingly used, as is external scrutiny of students’ work. But criteria for judging teaching performance at university level are ill-defined, and expectations of a lecturer, tutor or seminar leader often vary quite considerably within even a small group of students, as well as among external assessors. Thus the majority of teachers are usually accepted as competent if undistinguished. Indeed, the ‘inspections’ of teaching sessions – most of them lectures – undertaken during the 1995 quality assessment of teaching in geography in UK universities invariably rated the majority as ‘satisfactory’, with a substantial minority being deemed ‘excellent’ and very few – none in most cases – ‘unsatisfactory’ (Johnston, 1996a). In most universities now, promotion exercises require proven excellence in at least two of the three criteria generally considered – research, teaching and administration; some add a fourth criterion – service to the wider community.

Research performance is a major criterion for promotion, therefore, although a relatively undistinguished record in this area can be compensated by excellence elsewhere. Some argue that teaching competence is not only undervalued (despite the promotion of geographical pedagogy, notably through the Journal of Geography in Higher Education), but that as a consequence of the increasing emphasis on research and its financing in most universities, it has received less attention from the 1980s onwards (Jenkins, 1995; Sidaway, 1997). How is research ability judged? Details of how research is undertaken are considered in the next section; here the concern is with its assessment rather than with stimulus and substance.

Successful research involves making an original contribution to a field of knowledge. It may involve the collection, presentation and analysis of new information within an accepted framework; it may be the development of new ways of collecting, analysing and presenting material; it may comprise promoting a new way of ordering facts – a new theory or hypothesis, or simply new interpretations of and insights into existing material; or it may be some combination of all three (on the definitions of research and scholarship, see Collini, 2012). Its originality is judged through its acceptance by those of proven expertise in the particular field. The generally accepted validation procedure is publication, hence adages such as ‘unpublished research isn’t research’ and ‘publish or perish’.

The main publishing outlets for research findings in most disciplines are their scholarly journals, which operate fairly standard procedures for scrutinising submitted contributions. Some of the major journals are published by academic learned societies and others by commercial publishers (on the shifting relative status of these in geography, see Bosman, 2009), with many learned societies now contracting out the production and marketing of their journals to commercial publishers while retaining full editorial control (Luke, 2000; Johnston, 2003a). Manuscripts are submitted to the editor, who seeks the advice of qualified academics on the merits of the contribution; these referees will recommend either publication or rejection, or revision and resubmission. When accepted, a manuscript will enter the publication queue, which may be up to two years long, although increasingly journals are publishing accepted papers on their websites as soon as they have been accepted for publication.

Although widely accepted, this procedure is subjective because it is operated by human decision-makers. The opinions of both editor (on the manuscript and on the choice of referees) and referees may be biased or partial, so a paper can be rejected by one journal but accepted by another, even without alteration. (On the canons of editorship see, for example, Hart, 1990, and Taylor, 1990a; for a radical alternative, see Symanski and Picard, 1996.) Most disciplines have an informal prestige ranking of journals, and it is considered more desirable to publish in some rather than others, because of the stringency of their review procedures, their circu...