- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Representing the Environment

About this book

The development of the environmental movement has relied heavily upon written and visual imagery. Representing the Environment offers an introductory guide to representations of the environment found in the media, literature, art and everyday life encounters.

Featuring case studies from Europe, the Americas and Australia, Representing the Environment provides practical guidance on how to study environmental representations from a cultural and historic perspective, and places the reader in the role of active interpreter. The book argues that studying representations provides an important lens on the development of environmental attitudes, values and decision-making.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

This chapter:

- introduces the study of environmental representations;

- explains the structure and organisation of this book.

Contested environments

Few developments in contemporary thought owe more to the power of imagery than the emergence of the modern environmental movement. From the early days of that movement in the 1960s, environmentalists clearly understood the importance of finding powerful images to represent ideas that otherwise might be difficult to grasp. Few were more effective in this respect than the American genetic biologist Rachel Carson (1907–64).

Exercise 1.1

The extract below comes from Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring (1963), widely regarded as a founding work of modern environmentalism. This passage comes from the first chapter of the book, which is entitled ‘A Fable for Tomorrow’.

Summarise the case that Carson is making.

There was a strange stillness. The birds, for example – where had they gone? Many people spoke of them, puzzled and disturbed. The feeding stations in the backyards were deserted. The few birds seen anywhere were moribund; they trembled violently and could not fly. It was a spring without voices . . .

On the farms the hens brooded, but no chicks hatched. The farmers complained that they were unable to raise any pigs – the litters were small and the young survived only a few days. The apple trees were coming into bloom but no bees droned among the blossoms, so there was no pollination and there would be no fruit.

The roadsides, once so attractive, were now lined with brown and withered vegetation as though swept by fire. These, too, were silent, deserted by all living things . . .

In the gutters and under the eaves and between the shingles of the roofs, a white granular powder still showed a few patches; some weeks before it had fallen like snow upon the roofs and the lawns, the fields and streams.

No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves.

(Carson, 1963, 22)

Your answer might highlight the following:

- The silence of the countryside is due to elimination of much of the wildlife.

- The flora as well as the fauna seems to have suffered, with the suggestion that the entire rural ecosystem had broken down.

- The cause lies in the granular white powder that fell from the sky some weeks earlier, although it is unclear from this extract whether it was deliberately dropped, as in aerial spraying, or whether it was an accident.

- The idea that this is ‘a fable for tomorrow’ suggests that this might be a warning, of the type found in science-fiction literature, rather than description of an actual event.

The key to understanding this extract lies in knowing that the granular white powder was agricultural pesticide and that, although Rachel Carson was describing a hypothetical situation, all the individual elements had ‘actually happened somewhere’ (Carson, 1963, 22). Carson had become increasingly concerned about the arbitrary use of farm pesticides, particularly DDT (dichlorodiphenyl-trichloroethane), for their indiscriminate effects on wildlife. In the late 1950s, several American states had used DDT in widespread aerial spraying programmes aimed at pest control. Her book, which had the original working title The Control of Nature, appeared against the background of that programme and other instances of pesticide misuse (Payne, 1996, 142). Yet rather than being a straightforward academic counter-argument to the case for using agricultural pesticides, Carson created a powerful and easily understood vision of the potentially devastating consequences of uncontrolled usage. In the words of Stewart Udall, US Secretary of the Interior between 1961 and 1968, Silent Spring was ‘an ecology primer for millions’ and played an inestimable part in ‘the ecological reawakening of America’ (Udall, 1963, 137; Payne, 1996, 137).

Other early environmentalists followed similar strategies, also finding readily accessible images to convey complex ideas. One technique harnessed environmental arguments to popular themes of the day, such as space travel, concern about nuclear weapons and anxieties about population growth. Kenneth Boulding (1966), for instance, likened the earth to a single spaceship, in which resources needed constant recycling. Paul Ehrlich (1968) compared explosive population growth to a bomb possessing the capability to destroy existing patterns of life. Garrett Hardin (1968) put forward a parable of the behaviour of herdsmen tending cattle on common pastures as the basis for presenting more general principles about demographic increase and resource use. Although later criticised for being simplistic or misleading, these ideas were undeniably important for crystallising debate around easily grasped images.

The same strategy of introducing complex ideas by using striking images continues to this day, particularly by employing powerful visual images. For example, advertising campaigns by environmental groups have included the following photographic images:

- Factory chimneys belching out plumes of smoke.

- Industrial effluent spewing into rivers from corroded pipes.

- Trees dying from the effects of acid rain.

- Cars snarled up on urban motorways and emitting exhaust fumes.

- Unarmed protesters in small, vulnerable vessels confronting huge whaling vessels.

- Seal pups on the ice floes being clubbed to death by hunters.

- Oil-coated seabirds floundering on blackened beaches.

- Children staring at the carcass of a dead dolphin, washed up on a beach after an incident involving toxic chemicals.

The subject in question might be, among other things, global warming, environmental pollution, public health, caring for wildlife, the costs of ecological disaster or the case for public transport. Whatever the specific issue, the frequency with which such images appear certainly suggests that those who deploy them believe that they are effective in getting their message across.

Yet all such images are selective representations of complex issues. Those who design them actively campaign to awaken public consciousness over misuse of the environment and shape their communications to create and reinforce that message. Moreover, the exchange is not one way, since many actively contest the views put forward by environmentalists. For their part, corporate and industrial interests quickly learned that they too could employ powerful imagery to counter, sometimes pre-emptively, the claims of the environmental lobby (e.g. Wilson, 1992; Anderson, 1997). Industrial corporations in the energy, oil, tobacco and chemical industries, for example, routinely monitor current environmental debate. Many employ entire departments to take responsibility for relations with the press and broadcasting media, devising favourable materials for distribution. They sponsor ‘think tanks’ or pressure groups sympathetic to their interests, which produce seemingly independent reports and other materials aimed at influencing the public or politicians (Beder, 1997). They also commission corporate ‘green’ advertising, in which they present their activities as vigorously promoting a better environment. In turn, their readiness to promote their case leads environmental lobbyists, within the limits of their budgets, to employ professional agencies in the battle for public opinion. What was once an area of informal, even amateurish, communication on the fringes of mainstream political debate, now increasingly sees the involvement of media consultants and specialist agencies. Environmental debate has become a battleground where the contestants pitch their contrasting and equally selective representations of environmental problems at one another.

Environmental representations

So far, we have talked about the ‘environment’ in connection with environmental protest and activism. Yet while a convenient way to introduce the subject, these activities only represent the tip of an iceberg. Each day the media bombard us with countless images of familiar and less familiar environments. Billboard posters, property advertisements, food packaging, radio broadcasts, T-shirts and picture postcards, among many others, can all convey ideas and images of the world around us. Sometimes, the environments depicted are clearly chosen to illustrate the theme of a news item or story. Television journalists, for example, often position themselves in front of graffiti-covered walls or crumbling tower blocks when presenting items on life in the inner city. Newspapers carry pictures of semi-submerged homes and cars to make tangible more abstract discussion about, say, flood control or the long-term impact of global warming. Documentaries on economic change frame shots of landscapes scarred by the abandoned machinery and mineral workings of a previous age of industrialisation.

At other times, what appear to be incidental depictions of specific environments turn out to be conscious strategy. The film industry supplies many good examples. Directors of gangster and science-fiction movies commonly use dark and brooding urban-industrial sets to enhance their film’s message. Such cities are characteristically portrayed as overcrowded, claustrophobic, dark and violent; a place where good struggles to overcome inherent evil. The makers of period costume dramas often choose locations that feature cobbled city streets, which are either studio sets or real-world sites carefully screened to remove any tell-tale signs of modern times. Films with romantic story-lines are located in small towns surrounded by idyllic countryside, thereby linking the film’s content to images of pastoral tranquillity and perceived social stability. Similarly, films depicting the life and times of the extremely wealthy choose environments that testify to social exclusiveness, such as landed estates with their parklands and manicured lawns. In each case, choosing appropriate visual settings is vital for the plausibility of the action.

Contemporary product advertising shows similar sensitivities. Advertisers recognise that suitable environmental associations can enhance their selling message. For example, although now having a product often subject to official disapproval, cigarette advertisers work hard to associate their products with, say, the deserted Western landscapes of Marlboro Country or bustling café society (Virginia Slims). An advertising campaign for the British do-it-yourself chain Homebase showed a kitchen interior with the Eiffel Tower glimpsed from its window, attempting to counter the advertiser’s reputation for budget-conscious furnishings and fitments with suggestions of French chic and sophistication. Elizabeth Arden cosmetic advertisements find elegant women applying their makeup against a background of shops on New York’s Fifth Avenue or the Manhattan skyline. Food advertisers choose Alpine meadows as the backdrop for advertising Swiss cheese (‘Gruyère: the natural choice’) or a timeless Italian hilltop village as the setting to advertise Italian dairy products (‘Food from Italy: the quality of life’). Compact saloon cars designed for town driving appear against the sophisticated surroundings of modern detached villas (‘Volvo for Life’) or elegant town houses (‘Renault Avantime: there is no such thing as a casual observer’). Luxury four-wheel drive motor vehicles (see also Chapter 5) are set against the rugged grandeur of the Colorado Rockies (Jeep: ‘Don’t compromise. Anywhere’) or crossing a river in an African game reserve in the company of exotic wildlife (the ‘Land Rover Experience’).

We take the content of these advertisements for granted, often scarcely giving them a second glance when browsing through a newspaper or journal. Yet, when we know how to interpret them, they reveal much about the values of those who designed them and, more generally, about the meanings that places and landscapes hold.

Exercise 1.2

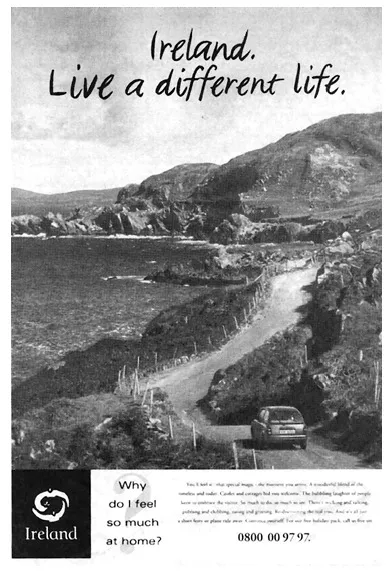

Look at the advertisement shown in Figure 1.1. It was placed by Holidays Ireland, a tourist agency, in May 1997. It appeared on the front page of the Independent, a British broadsheet daily newspaper catering for a predominantly middle-class readership.

What message do you think the advertisers are trying to put across to the newspaper’s readers?

Figure 1.1 Holidays Ireland advertisement, May 1997. Courtesy of Tourism Ireland Ltd

The answer that you have reached depends on what you are looking for, on your previous knowledge and on the information that you have available. Although seemingly uncomplicated, this advertisement carries a surprising variety of meanings. It can be interpreted:

- In terms of photographic technique. There are many ways to take a photograph and professional photographers are trained to use their skills to get the result that they want. The person responsible for this picture will have made choices about the composition, the angle of regard of the camera, the lens to use, and the exposure. As this picture was taken using conventional film rather than digital technology, the photographer also chose the appropriate film and probably also the methods for developing it. Each of these elements can make a difference to the final picture. Looking at Figure 1.1, we can infer that the monochrome photograph that occupies most of the advertisement was taken with a wide-angle lens from a high vantage point. Reproduced in portrait format (where the vertical dimension is greater than the horizontal), it offers considerable depth of field and sharp focus from foreground to the far distance. These techniques, which some might call ‘tricks of the trade’, are ways of giving a three-dimensional appearance to a scene that by definition is rendered in a two-dimensional form (a photograph on a flat page).

- An example of pictorial composition frequently used in promoting Irish tourism. It illustrates the sunlit summer face of the sparsely populated and rocky West Coast of Ireland. The single car conveys a sense of solitude, with the road winding into the middle-distance drawing the eye to the ‘unspoiled’ scenic splendours that lie ahead. In case these landscapes should seem unappealingly isolated, the caption stresses that the experience of seclusion is combined with liveliness, hospitality and the ‘bubbling laughter of people keen to embrace the visitor’. Yet returning to the photograph, it is worth remembering that the picture that we see will have been chosen after lengthy decision-making. A photographer on location invariably takes many pictures, experimenting with different locations and perspectives, with combinations of near and far objects, as well as with light, focus, film and lenses. The photographer then supplies a set of photographs for consideration and may, or may not, be party to the final decision as to which to select. Indeed the graphic designers (who designed the advertisement), or the advertising agency (that placed the advertisement), or senior executives at Irish Holidays (who commissioned the campaign) or any combination of them, may have made the final choice.

- As part of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Series Editor’s Preface: Environment and Society Titles

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Studying Environmental Representations

- 3. Representations In Context

- 4. The Classical, Medieval and Renaissance Legacies

- 5. Enlightenment and Romanticism

- 6. Empire, Exploitation and Control

- 7. Representing Urban Environments

- 8. Historic Cities, Future Cities

- 9. Conclusion

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Representing the Environment by John R. Gold,George Revill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.