![]()

1

Cultural Diversity of African Pygmies

Serge Bahuchet

A Brief History

In the second half of the nineteenth century, European and American explorers encountered various groups all over Central Africa that appeared physically different from other peoples with whom they shared the same rainforest. Whenever such a group was discovered, they were commonly recorded under the homogenous category “Pygmy,” after the mythical population of short stature described in Greek antiquity. Other, similarly indistinct names were given depending on the nationality of the explorer: Dwarfs, Zwergen, Nains, or Négrilles (little Negroes), to name a few. It became a great endeavor of travelers in the region to find and record “new” Pygmy groups living in the yet hidden corners of the Congo Basin (Bahuchet 1993a). Some sort of competition developed to discover those with the shortest stature and living the most “primitive” lifestyle, that is, nomadic, hunting and gathering, and living in beehive-shaped huts constructed of leaves and branches. The observers of this time were unconcerned with questions of cultural diversity; on the contrary, they were interested in a unity among all Pygmies that would serve as proof of the persistence of some prehistoric way of life, pure and monotheist. Many of the confusions of this early period persist even today. Professional scientific observations of specific groups began quite late. Among the first were those of Paul Schebesta, who in the 1930s lived and worked with the BaMbuti people of the Ituri rainforest, located in the remote eastern part of the Congo Basin. Schebesta wrote a series of immense tomes (1938, 1941, 1948, 1952) detailing the techniques, societies, languages, and vocabulary of the BaMbuti people. He was the first scholar to recognize that within these groups there were various subgroups called by different names—Asua, Efe, BaSua, and Kango—and that discrete languages were spoken by each.

In the 1950s, Schebesta was followed by Colin Turnbull (1965a, 1965b). Critical of Schebesta’s methodology, Turnbull developed a summary ethnography of the BaMbuti, emphasizing a strong technological difference dividing two groups: those who practiced net-hunting—those of the subgroup BaMbuti, or BaSua—and those who practiced bow-hunting—the Efe (Turnbull 1965a). He found that beyond the linguistic diversity recognized by Schebesta among these African rainforest populations, there was in fact profound cultural diversity, and he was the first to plead for a careful distinction to be made between them: “The term ‘Pygmy’ leads far too easily to meaningless generalization” (Turnbull 1965a).

Turnbull did not go far enough. He still considered the people of the Ituri essentially homogenous, without questioning the actual relations between groups that did not speak the same languages (Turnbull 1983). As a matter of fact, after many years of often fine anthropological studies in various regions of the Ituri, we still lack ethnographic descriptions of the social exchanges between, for instance, the Efe and the Mbuti.

Despite the initial advances made by Turnbull and Schebesta in recognizing the tremendous degree of diversity among “Pygmies,” their work also contributed strongly to the lasting stereotype of the “true Pygmy” that has permeated much of the literature since. Contrary to the stereotype, there are in fact extensive variations and permutations in virtually every facet of Pygmy life and culture. Rather than in the deep rainforest, some groups have been found to live on the savannahs, some in the forest-savannah ecotone, and some in the mountains or swamps. Others, though short-statured, are not hunter-gatherers; while for some the reverse is true. An excellent illustration of this point comes from the lengthy and important fieldwork done with the BaTwa in Rwanda by Peter Schumacher (1949–1950), a contemporary of Schebesta. This group diverged greatly from the stereotype; they were living in the mountains and were not hunter-gatherers but potters, servants, and musicians in a complex caste society. The books of Schumacher, however, are never used in any discussion about the Pygmy populations.

As time progressed, researchers gradually woke to the fact that the peoples and cultures of the Congo Basin were indeed far from uniform: they populated diverse environments from the rainforest to the savannah and displayed a broad spectrum of physical, linguistic, and cultural traits. To date, the African rainforest foragers collectively known as Pygmies have been the subjects of thousands of publications, though they are of varying quality and accuracy (Plisnier-Ladame 1970; Hewlett and Fancher 2010). Although some of these publications have contributed concretely to furthering the anthropological discourse on central African rainforest peoples, the majority of the documentation consists of weakly supported, generalized statements. Altogether, despite the apparent abundance of literature on these foragers, great gaps remain in our knowledge.

Thus, after almost a century of anthropological research in central Africa, we are still confronted with numerous difficulties. As a consequence of the uneven quality and quantity of description and information about the various groups, many important questions remain unanswered. One of the foremost of these regards the validity of the term Pygmies to describe African rainforest foragers: Do the various populations to whom it refers bear any meaningful commonalities? Is it perhaps more relevant to compare the differences and similarities among the Pygmies themselves than to compare them as a single group against other African foragers or against all other central African populations?

Names and Locations of Groups

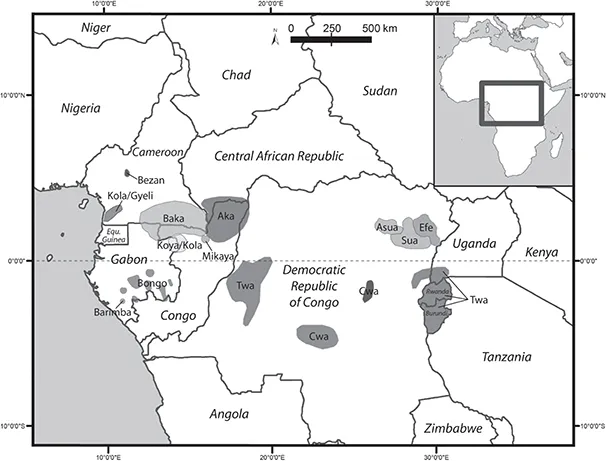

In spite of the immense physical, cultural, and linguistic diversity among Pygmy peoples, an imbalance in the literature has given rise to the popular stereotype based on “forest-oriented” groups. These most famous of Pygmies are typified by their short stature, seminomadism, hunting and gathering, use of temporary camps with domed huts, and regular exchange with neighboring farmers (Hewlett 1996). The forest-oriented groups, in geographic order from the Atlantic coast to the eastern Congo Basin, are as follows:

• Baka (some of them known as Bangombe) (Joiris 1992, 1996; Leclerc 2001, 2012; Sato 1998; Tsuru 1998; Vallois and Marquer 1976)

• BaAka1 (also Bayaka, also known as Babinga or Bambenga, some of them—the western groups—known as BaMbenzele) (Bahuchet 1972, 1985; Demesse 1978, 1980; Hewlett 1991; Kitanishi 1995; Lewis 2002)

• BaMbuti of Ituri forest, northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC, formerly Zaire). This last group is actually divided into at least three ethnic groups: Efe, Asua, and BaSua (or BaMbuti, strictly speaking2) (Bailey 1991; Demolin 1993; Harako 1976, 1981; Ichikawa 1978, 1981, 1983; Peacock 1984, 1985; Schebesta 1941; Tanno 1976, 1981; Terashima 1983, 1985, 1998; Turnbull 1965a, 1965b, 1983).

Other groups live in a markedly different socioeconomic situation; having settled in villages, they practice a more or less efficient agriculture in addition to foraging while maintaining relations with neighboring farmers. Although they appear less distinct from farmers than the preceding groups on cultural and often physical bases, they are always distinguished and categorized by farmers as different from themselves. They are, from west to east,

BaKola (also known as BaGyeli, southwestern Cameroon) (Biesbrouck 1999; Joiris 1992, 1994; Koppert et al. 1997; Ngima Mawoung 1996, 2001; Seiwert 1926)

BaBongo (also known as Akoa, central Gabon) (Andersson 1983; Annaud and Leclerc 2002; Knight 2003; Le Bomin and Mbot 2012a; Leroy 1928 [1897]; Matsuura 2006, 2011; Mayer 1987)

BaKoya (sometimes called BaKola, at the border of Gabon-Congo) (Soengas 2009, 2010, 2012; Tilquin 1997)

BaTwa (in the Equatorial region in western DRC) (Elshout 1963; Pagezy 1975, 1976, 1986, 1988; Schultz 1986; Sulzman 1986)

Figure 1.1. Group names and locations.

Other, less well-known Pygmy groups that live on the forest periphery have been documented in only a few papers or reports. These groups are generally less mobile and live in settled villages, sustain a low population, and practice a more or less efficient agriculture. Meanwhile, like seminomadic groups, they maintain relations with neighboring farmers. The groups called Kola, BaBongo, BaKoya, and BaTwa live in the rainforest, while the Bedzan, various groups named Cwa (read “Tshwa”) and a scattered group known under the name of BaTwa live on the savannahs at the periphery of the forests in Rwanda and Burundi. These groups are (again, from west to east)

BaKola, BaBongo, BaKoya, and BaTwa, who live in the rainforest.

Bedzan3 living with the Tikar in central Cameroon (Leclerc 1995, 1999; Mebenga Tamba 1998).

BaCwa (pronounced “Batshwa”), several groups under this name live in the southeastern savannah of Congo Democratic Republic (Kazadi 1981; Vansina 1954).

BaTwa, the name of scattered groups in Rwanda and Burundi. They are not foragers, but farmers and handworkers (potters), constituting a caste in highly hierarchized societies of Rwanda (Lewis 2000; Lewis and Knight 1996; Schumacher 1949–1950).

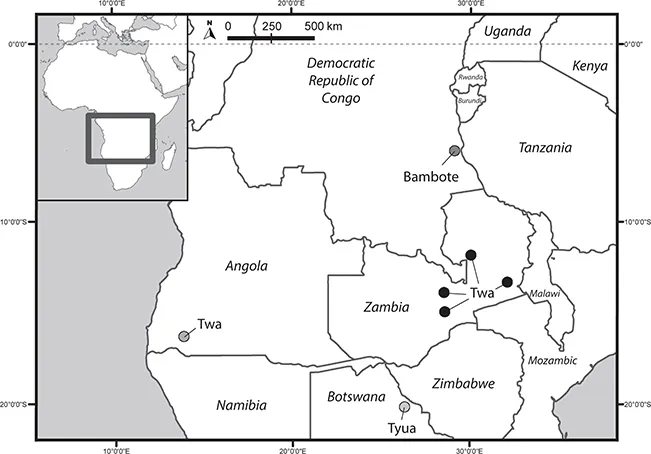

I must also mention that there are still other groups in southern central Africa (see figure 1.2), but their documentation is very meager and their status remains ambiguous as a result. They are not called “Pygmies” by any of the authors, but their names look similar to those of Pygmy groups in the Congo Basin. These are the Vatwa in southwestern Angola (Estermann 1962, 1976), the different Batwa swamp fishermen in Zambia (Rosen 1925; Macrae 1934; Barham 2006; Haller and Merten 2008), as well as the Bambote of the shores of Lake Tanganyika (Terashima 1980).

Figure 1.2. Groups with ambiguous status.

Orientation of the Literature

The forest-oriented canonic stereotype of “true Pygmy” originated during the first phase of “classical ethnography,” conducted on the BaMbuti of the Ituri Forest in the east of the DRC (Schebesta 1938, 1941, 1948, 1952; Turnbull 1965a, 1965b, 1983). Japanese scholars followed in the 1970s and 1980s, couching their numerous studies in the area within the framework of cultural ecology (Harako 1976, 1981; Ichikawa 1978, 1981; Tanno 1976, 1981; Terashima 1983, 1985; Terashima et al. 1988). American anthropologists then focused on one of the BaMbuti subgroups, the Efe, for a long-term biocultural study (Bailey 1991; Bailey and DeVore 1989; Bailey and Peacock 1988; Ivey 2000; Peacock 1984, 1985).

The research expanded in the late 1970s to include the BaAka (known previously as Babinga, or Bayaka), whose range was in the western part of the Congo Basin. Monographs on this new group, also forest-oriented, by Demesse (1978, 1980) and Bahuchet (1972, 1985) were accompanied by ethnobiological (Bahuchet 1985; Motte 1980) and musicological (Arom 1987) research, and a multidisciplinary study focused on their language (Thomas et al. 1981–2013). Other anthropological studies have recently been done on the Baka, the largest Pygmy group in Cameroon (Sato 1992), with further material and insight offered by the dissertations of Joiris (1998) and Leclerc (2001).

The historical aspects of hunter-gatherer culture began to garner interest in the 1980s (Leacock and Lee 1982; Rottland and Vossen 1986). This was an important step, especially for the study of rainforest populations, whose cultures are deeply intertwined with their sedentary neighbors. Indeed, since Turnbull’s book Wayward Servants (1965b), the discourse on Pygmy groups has been conditioned by questions concerning this close, mutually dependent relationship, even in publications not directly pertaining to the topic (cf. Bahuchet and Guillaume 1982; Terashima 1998; Vansin...