I

Puran Sahay was sitting at the Block Development office when he heard the account of this unearthly terror.

His grandfather had named him Prarthana Puran—Prayer Fulfillment—for Puran’s mother was producing one girl after another, and Puran’s father had just left the Congress volunteers and become a Comnis [Communist] and was most unwilling to marry a second time for a son—in those days one could have called it a revolt.

Even Puran’s mother had told her husband, “Get another wife. Our line will die without a son.” The Father, “As a Comnis I cannot marry again.”

— But a daughter will not carry the name.

— Son and daughter are the same to me. I’ll send the girls to school, they’ll be full human beings. I’m proud to be a father of daughters.

A disobedient son, but one must have a male child to preserve the line. So Grandfather went to the four great sacred places of India and offered his prayer. After all this the grandson was born. That is why he was given the name of Prarthana Puran. Among his father’s friends there were journalists and poets who also came to the house. The grand name might owe something to their high-toned conversations as well. Long after Grandfather’s demise, when he was himself a journalist, ex-social worker, and independent, he changed his name.

Which half to cut. Which to keep. A great problem. “Prarthana” becomes a woman’s name, his wife’s name was Archana. So he kept the name “Puran.” His wife was very lively. She would say, “If we have a girl we’ll call her Prarthana.” But Prarthana didn’t come into Archana’s lap. It was Arjun who came. But just after Arjun arrived Archana died of eclampsia. Puran didn’t marry again. Arjun spent some time with his mother’s brother and then returned to Puran’s mother. To him “Mother” means the faded photograph of a smiling Archana on the wall. At fifteen, neither adolescent nor young man, Arjun is a good student at the “Udyog” School. Puran’s mother manages the house with a firm hand even at seventy-five. She is protecting the money left by husband and father-in-law and the house at Kadamkuan. She has no confidence about Puran. She will make a marriage for Arjun as soon as he’s twenty. Puran is as obstinate as his father. He hasn’t married since Archana died. Although, in middle age, he tastes loneliness.

Puran’s elder sister lives in the neighborhood, so Puran’s mother is not altogether helpless. Puran can thus circulate at will as a reporter for the group of daily, weekly, and monthly papers Patna Dibasjyoti (formerly Patna Daylight). Now he feels like marrying his sister’s unmarried teacher sister-in-law Saraswati. It would have worked out if he had married her a bit before this. Now Arjun is growing up, a certain barrier of diffidence has come between Saraswati and Puran. Puran doesn’t know what Arjun will say. Arjun, with his English-medium schooling, his attraction for karate, his hockey-playing, has remained a stranger to him. He has become even less tractable after his wits have sharpened in science and mathematics quizzes.

Puran understands that if he goes here and there no spot is left empty at home, for he has long since not been there when he’s there. Mother’s household is sufficiently replete with Arjun, with the Gita, with her two daughters in Patna. Arjun’s personal universe is most important to him. The elder sisters inhabit a distant world. They find it hard to understand that Puran, a male of the species, does not make his masculinity felt in harsh words, in manifestations of heat and light. Saraswati herself understands that no real relationship has grown between herself and Puran. Saraswati considers herself squandered. As if her life has floated away like the fruit-offering at the Chhat festival, unaccepted by the sun. The river doesn’t eat it, it is not for human or animal consumption, it only floats, and rots floating.

Saraswati’s glance says: it’s your failure that there was no room for a fleshly, hungry, thirsty, human relationship to grow. Puran accepts that and considers himself half-human at forty-five. And this moral question arises: how will a person merely floating in the everyday world, who has not attempted to build a human relationship with mother-son-Saraswati, be able to do justice to a subject as a journalist?

Yet as a journalist his reporting of the massacre of the harijans at Arwal has received praise, and he too, like others, has fallen into disfavor with the Government in Patna. He wrote about the killing in Banjhi with a razor-sharp edge: “Red Blood or Spark of Fire in Black Tribal Skin?” And then water scarcity in Nalipura. Enteric fever epidemic in Hataori. The blinding of prisoners in Bhagalpur- the owner of the Dibasjyoti group is a Punjabi industrialist. He is untroubled by the maelstrom of political moves in Bihar or the pre-historic warfare of casteism. He gives money to all political parties. He has support everywhere. The newspaper is a business to him. If reporting caste war keeps his paper going, so be it. Nothing will touch him. Industrial set-up in Ranchi, clout in New Delhi and Bihar, newspaper in Patna. The illustrated magazine called Kamini, devoted to women and the film world, brings in most money. Right beside a balance-sheet on suicides are recipes on the “For the Home” page. Right beside the world travels of an international Guru the statement of a sex-bomb star: “Motherhood is woman’s greatest wealth.” This sort of a mixed chow mein dish.

Even in this life Puran felt restless. He sensed that he was getting altogether too professional. First investigative journalism, but then no problem writing “Bihar, A Tourist’s Paradise.” His father had faith in communist ideals. His life was not adrift. But Puran cannot be happy in himself. He has done as he pleased. Yet where is the sense of achievement fulfilled?

These are his reasons for coming to Pirtha. Before he left, Saraswati startled him by saying, “I’ll no longer wait for nothing.”

— What will you do?

— I’ll go to an ashram with a school.

— Not right away?

— And why not?

Saraswati spoke with a gentle smile. For a long time now, she has worn only white. In her white sari, white blouse, and with her long braid and tired dark eyes she looked like Nutan in the tragic film Saraswati Chandra (they’d seen it together). The theme song “O driftwood face, O unquiet mind” played in his mind.

— Saraswati, why an ashram?

— I’m thirty-two, after all.

— Let me come back.

— Your life won’t be empty without me.

— Give me a bit more time.

— I’ve been waiting for you, fighting the family, since I was eighteen. My younger sisters are all married off. Now at last I’m weary too.

— Only this once, Saraswati.

She wears only white, as if already a widow.

— This once.

— I can’t give my word.

Puran has come to Pirtha with the worry that Saraswati might leave some day. The district is in Madhya Pradesh, the Block is Pirtha. He must go to the distant villages where the eighty thousand tribals among the one million, one hundred and seven thousand, three hundred and eighty-one people of the district live. For a long time people have been dying in Pirtha. Well, the Chief Minister of the state, who built himself a luxurious residence after the Bhopal Union Carbide disaster, is certainly not about to declare Pirtha a “famine area.” But Puran’s old friend Harisharan, now Block Development Officer; wrote, Come, take a look, the State Government says “No story,” but here’s Surajpratap’s report, come to follow it up.

He came for this purpose, and sensed already in Madhopura that a good deal of hostility was afoot against journalists not only in Pirtha Block but in the entire district.

The SDO [Sub-Divisional Officer] said, “Why are you going to Pirtha? There’s nothing there. There’s nothing more to be seen in the tribal areas. You’ll make a noise in the newspaper if you say anything, and more journalists will come. There will be a furor.”

— It doesn’t matter to you folks after all.

— You don’t understand. Nothing matters to anyone these days. Nothing happens to anyone. Look, look at this.

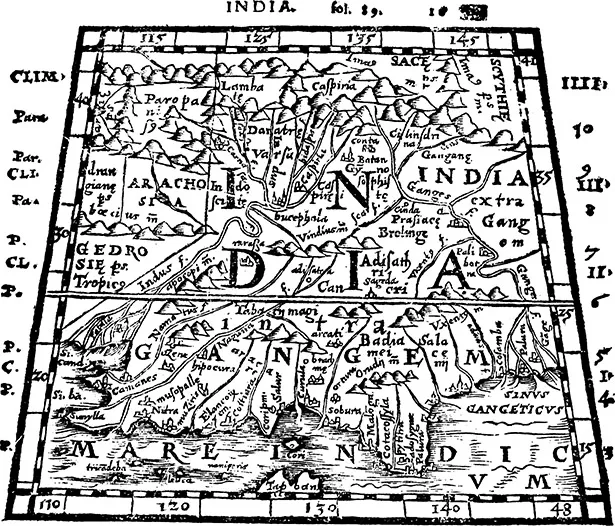

The survey map of Pirtha Block is like some extinct animal of Gondwanaland. The beast has fallen on its face. The new era in the history of the world began when, at the end of the Mesozoic era, India broke off from the main mass of Gondwanaland. It is as if some prehistoric creature had fallen on its face then. Such are the survey lines of Pirtha Block.

— Come and see. What, looks like an animal, no?

— Yes. But these creatures are extinct.

— Who knows?

The youthful SDO pulls the hair on his head.

— Our honor was destroyed by the Bhopal gas incident.

— How?

— There was talk about Bhopal. And in the middle of the gas affair in Bhopal, the state government did not permit a Health Center in Pirtha, and they were bringing the enteric patients from the tribal areas into town. The SDPO [Sub-Divisional Police Officer] fired in the dark, three people died. The enteric fever started from the polluted water supply. We sent water, it’s coming, it’s coming; the water tank didn’t get there. Both the truck and the tank had disappeared. I myself had posted guards at the polluted wells. The tribals then beat up the guard, drank the water, and then: Epidemic.

— What did you do?

— Sent police to stop the violence.

— And the police?

— Hey journalist! Pirtha is not agricultural land, and there is no struggle here. So what do the police do in such a tribal area?

— Where did the enteric fever come from?

The SDO laughs with a vicious joy.

— When it rains, the water flows down the hillside. How do I know if something poisonous came with the water?

— It does rain then?

— From time to time. Otherwise how are they alive?

— Doesn’t the state government give any aid?

— What aid? What resource? Look at this map. Near the foot of the animal there is a church but no missionaries. We are forty kilometers to the south of this church. And a canal would have gone from the animal’s tail to its head by the Madhopura Irrigation Scheme. The scheme is in the register. That canal would have joined the Pirtha River as well. And look here.

— I’m looking.

— The tribals are in the animal’s jaws. Near the throat water gushes down into Pirtha at great speed in the rainy season. If there were small dams three miles down the river, and then another mile down, the tribal area of Pirtha would be green.

— This didn’t happen?

— No. Eleven years ago there was great pomp and circumstance on Independence Day. We sent food. There was a camp, the minister came, there was an inauguration ceremony, and many reporters came.

— I didn’t come.

— It began where it ended.

— It didn’t go any further?

— No no, it would have advanced if it had begun. Three SDOs have tried in turn, but these files get lost halfway between Madhopura and Bhopal. They always get lost. I...