- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Motor and Sensory Processes of Language

About this book

Published in 1987, Motor and Sensory Processes of Language is a valuable contribution to the field of Cognitive Psychology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Motor and Sensory Processes of Language by Eric Keller,Myrna Gopnik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

History & Theory in Psychology1 Jacques Lordat or the Birth of Cognitive Neuropsychology

André Roch Lecours

Jean-Luc Nespoulous

Dominique Pioger

Jean-Luc Nespoulous

Dominique Pioger

ABSTRACT

A few aspects of Jacques Lordat's life, personal experience of aphasia, interactions with his contemporaries, teachings, and scientific influence are outlined. Lordat is presented as a (if not the) founder of aphasiology. It is underlined that his approach to aphasia was very much akin to that of modern cognitive neuropsychology.

Jacques Lordat (Fig. 1.1) was born in Tournay, near Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées, on February 11th, 1773. In 1793 he became a military hospital student in surgery (“admis dans les hôpitaux militaires comme élève en chirurgie”) (Larousse, 1878); thus, part or all of the training which led to his title of military surgeon (“chirurgien militaire”) took place in Plaisance, Gers, where, according to Bayle (1939), Lordat was the disciple of a Doctor Broca.

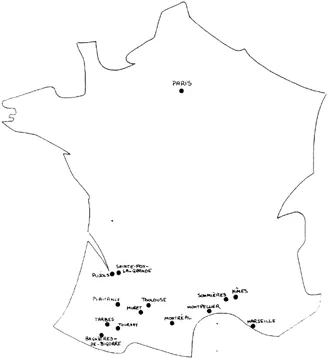

Now, Schiller (1979) points out that “Broca” is not a common name and that the Broca family (which included a number of soldiers and doctors) was a tightly knit group. However, one only has to glance at a map of France (Fig. 1.2) to see that Plaisance is less than 150 kilometers south of Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, Gironde, where Pierre Paul Broca was born in 1824 and where his family had in all likelihood dwelt since the second half of the 16th century (Schiller, 1979). One wonders if young Lordat's first mentor, Doctor Broca of Plaisance, lived long enough to keep an eye on the earlier phases of

FIG. 1.1 Jacques Lordat teaching at the Faculty of Montpellier (circa 1860).

his disciple's medical career. One also wonders when, and in what circumstances, Pierre Paul Broca—whose father, Jean-Pierre dit Benjamin, was also a medical doctor—first heard about speech disorders resulting from brain lesions.

Lordat soon left Plaisance to study medicine at the famous Faculty of Montpellier, which in those days was considered by many scholars to outrank the faculty of Paris. Lordat's link to the Montpellier School of Medicine was a long lasting one. In 1797, at the age of 24, he received his diploma of Doctor in Medicine. Two years later, after having served as a prosector, he was teaching at the Faculty as a “Professeur libre.” Tenure came in 1811 when, then aged 38, Lordat was appointed “Professeur agrégé de médicine opératoire.” In 1813, when Dumas died, Lordat succeeded him as “Professeur titulaire de la chaire de physiologie,” an appointment that he retained for half a century (including the period when he served as Dean of the Faculty; Bayle, 1939), that is, until a little before his 90th birthday. It was Lordat's overt opinion that, just like the cardinals of the Roman church, the professors of great medical schools should never retire (Lhermitte, personal communication, 1984).

Lordat died in Montpellier, on April 25th, 1870, at the age of 97 (Bayle, 1939). By then, Paul Broca had lost his interest in aphasia, or rather

FIG. 1.2 The Hexagon.

aphemia, and, before becoming a Republican senator (Schiller, 1979), he had turned his attention and energy to worthier causes such as demonstrating that, although German big-brainedness became an obvious artifact once one's data were cleaned with great scientific care, women did indeed have smaller brains than men, and that Negroes did indeed have smaller brains than white men, and therefore that “‘inferior’ groups are interchangeable in the general theory of biological determinism,” and therefore that “social rank reflects inner worth,” and so forth (Gould, 1981).

Schiller (1979) wrote that “the subject of loss of speech is in several ways tied to Montpellier, where Lallemand had been interested in it and where Lordat had given in 1820 (sic) a classical account of the mechanism and psychology of speech and its clinical disorders” (p. 193). Schiller's bibliogra-phy indicates that he found this information on Lordat's 1820 contribution in Ombredane's “L'aphasie et l'élaboration de la pensée explicite” (1951). Now, if one goes to pages 47 and 48 of Ombredane's most remarkable monograph, one can read interesting comments on Lordat's teachings as published in 1843, not 1820.

Before Schiller, Moutier, a few weeks before he was dismissed by Pierre Marie in 1908 (Lecours & Caplan, 1984; Lecours & Joanette, 1984), published his inaugural dissertation entitled “L'aphasie de Broca.” The first section of this monumental book deals with the evolution of ideas concerning the mutual relationships of brain and language. Moutier (1908, p. 16) mentions three publications by Lordat: a paper printed in 1820, a book entitled analyse de la parole and published in 1823, and the well known Montpellier lessons of the 1804s, published in two consecutive issues of the Journal de la Société de médecine pratique de Montpellier (1843). Moutier raises several points in relation to the 1823 book, and he claims that this publication and the earlier one are much clearer and far more enlightening than the lessons published in 1843.1 But then, when one consults the astonishingly exhaustive bibliographical index of Moutier's dissertation, in which are listed nearly 1,500 references on aphasia and related topics, one finds (p. 689) an 1820 reference to a paper written by Lordat in a journal identified by Moutier as Revue périodique de la Société de médecine de Paris, and also (p. 690) an 1843 reference to the Lordat lessons published in Montpellier. No reference is provided in relation to the 1823 “enlightening” monograph.

Likewise, before François Moutier (1908), Armand Trousseau (1877) had alluded to Lordat's early publications on aphasia (cf. infra), and before Trousseau the Daxes, father and son, Marc and Gustave, both of whom were of strict Montpellieran obedience. In brief, this latter story is the following:

Act I

In July, 1836, Marc Dax, who was then practicing medicine in Sommières, a small town in the vicinity of Nîmes (Fig. 1.2), submits and probably reads a paper at the “Congrès méridional de Montpellier” (Hécaen & Dubois, 1969). In this paper, Dax, the father tells about his own clinical and anatomical observations as well as those of others, and he concludes that acquired disorders of “verbal memory” are the result of lesions of the left but not of the right cerebral hemisphere. This communication is not published in Montpellier, as it might have been—although it seems to be a recognized fact that, contrary to the Faculty of Paris, the Faculty of Montpellier traditionally gave credit to oral transmission of knowledge at least as much as, and conceivably more than, to written documents (Bayle, 1939; Guedje, personal communication, 1984). The original manuscript is lost but Dax has a copy. Marc Dax dies in 1837 and his son inherits the copy as well as his father's practice and, apparently, his preoccupation concerning the lateralization of the brain lesions responsible for acquired disorders of “verbal memory”.

Act II

According to Quercy (1943), whom we believe to be a particularly reliable historian of early French aphasiology, the sequence of events is thereafter the following: Scene I: On March 24th, 1863, Gustave Dax officially deposits his copy of the paternal manuscript at the “Académie de médecine,” in Paris, together with a paper of his own on the same topic; Joynt and Benton (1964) might be right when they suggest that Marc Dax was not ready to claim priority in 1836, but it is quite clear that Gustave was in 1863. An editorial committee is then appointed by the Academy, which decides not to publish the Meridional manuscripts for the time being (Hécaen & Dubois, 1969). Bouillaud is a member of this committee (Bayle, 1939). Scene II: Hardly a month later, in April of 1863, Broca publishes an updated version of his Exposé de titres et travaux, in which he raises the possibility of left hemisphere specialization for language. When the Exposé comes out in printed form, it is dated 1862 rather than 1863 (Quercy, 1943). As Bogen and Bogen (1976) wrote about Wernicke's 1874 representation of the speech area at the surface of a right hemisphere, this was probably “more in the nature of a printer's error than anything else”. Scene III: Broca (1863) strikes again in May, this time through a note entitled “Siège du langage articulé” and published in the Bulletin de la Société d'anthropologie (Bayle, 1939). This is not yet the 1865 paper but Broca is explicit enough and, according to Quercy (1943), this note is the document that led Bouillaud, and Paris after him, to attribute priority to Broca rather than Dax: “Broca avait précisé en 63 et Bouillaud lui accorda l'honneur de la découverte'.” Interestingly enough, in his May note to the “Société d'anthropologie” (of which he was the most influential founding member), Broca refers to a January note to the “Socité de biologie” that preceded the Gustave Dax move at the Academy. Of this January note, Quercy (1943) devastatingly writes, as it were en passant: “Je ne l'ai pas trouvée (I did not find it)”.

Act III

The Dax papers are finally exhumed and published in 1865, Marc's first and Gustave's immediately following, in the April 25 issue of the Gazette hebdomadaire de médecine et de chirurgie. Broca's best and most famous aphasia paper (the one everyone has heard of and the one one quotes, whether or not one has read it, whenever the question of priority is raised) is published a little less than 2 months later, in the June 15 issue of the Bulletin de la Société d'anthropologie.

Act IV

In 1879, a Doctor R. Caizergues, of Montpellier, reports in the Montpellier médical that he has found the original manuscript of Marc Dax while classifying the papers of his grandfather, Professor F.C. Caizergues, who was the Dean of the Faculty of Montpellier in 1836, at the time of the “Congrès méridional.” This fact is mentioned by Bayle, in 1939, by Joynt and Benton in 1964, and by Hécaen and Dubois, in 1969.

Now, this was a longish digression, although not without interest nor without purpose. What we were in fact driving at, on the one hand, is that the post-mortem 1865 paper by Marc Dax includes references to four researchers: The first is Gall, of course, and the second, Bouillaud, of course. The third is a German physician, whose mangificient name is Atheus although he wrote in Latin: “Observatum a me est plurimos, post apoplexiam, aut lethargum, aut similes magnos capitis morbos, etiam non praesente linguae paralysi, loqui non posse quod memoriae facultate extincta verba proferanda non succurant.” Marc Dax writes that he has excerpted this passage from a book edited (?) by Schenkius in 1585, that is, 280 years before the nearly joint publication of his own and Broca's manuscripts. The fourth researcher quoted by Marc Dax in 1865, or rather in 1836 if Gustave did not alter his father's manuscript, is Jacques Lordat. Marc Dax writes that Lordat's ideas on verbal amnesia are more in line with his own than are Bouillaud's (Dax senior could not know that Bouillaud would be there to chair the 1863 committee), and he quotes two early papers by Lordat: one in the September 1820 issue of the Recueil périodique de la Société de médecine de Paris, probably the same that Moutier quoted in 1908 as published in the Revue périodique de médecine de Paris (cf. supra), and the other in the September 1821 issue of the Revue médicale (p. 25).

And what we were driving at, on the other hand, is that there exists a problem with Lordat's early publications (1820, 1821, 1823): We tried to find them, but without success. Bayle (1939), who was much closer to the sources than we are in Montréal, tried before us, also without success. Nonetheless, Bayle (1939) found a paper by Bousquet in which he sees proof that Lordat's teachings were known in Paris before Bouillaud's initial paper on aphasia:

As you know, Gentlemen, the musculary movements of speech production succeed to one another as a result of habit, so that one movement calls the next without the intervention of will power. These chains of movements correspond, and I borrow this expression from Monsieur Lordat, to a form of bodily memory (“mémoire corporelle”), which is sometimes mistaken for a mental memory although these two forms of memory represent phenomena that are quite different. (Bousquet, 1820)

Be this as it may, Bayle's (1939) conclusion concerning Lordat's “early pub-lications” is that they never existed, a point of view that we find difficult to share if only because it is somehow disquieting to ignore bibliographies that were constituted by Marc Dax (1865), Adolf Kussmaul (1876), Armand Trousseau (1877), François Moutier (1908), and Francis Schiller (1979). And the whole affair is of some interest because, if Bayle (1939) is right, it follows that the Marc Dax publication of 1865 was at least in part a fraud: Given that he died in 1837, how could he have quoted papers by Lordat if Lordat did not write on aphasia before 1843? But if Bayle (1939) is wrong, Lordat (1820, 1821, 1823) rather than Bouillaud (1825) deserves the credit of having been the founder of French aphasiology.

For the time being, given our subject matter, we will have to rely exclusively on Lordat's 1843 Montpellier publicati...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: The Neuropsychology of Motor and Sensory Processes of Language

- Chapter 1 Jacques Lordat or the Birth of Cognitive Neuropsychology

- Chapter 2 The Role of Word-Onset Consonants in Speech Production Planning: New Evidence from Speech Error Patterns

- Chapter 3 Production Deficits in Broca's and Conduction Aphasia: Repetition versus Reading

- Chapter 4 Damage to Input and Output Buffers—What's a Lexicality Effect Doing in a Place Like That?

- Chapter 5 Phonological Representations in Word Production

- Chapter 6 The Cortical Representation of Motor Processes of Speech

- Chapter 7 Programming and Execution Processes of Speech Movement Control: Potential Neural Correlates

- Chapter 8 Intrinsic Time in Speech Production: Theory, Methodology, and Preliminary Observations

- Chapter 9 Kinematic Patterns in Speech and Limb Movements

- Chapter 10 Routes and Representations in the Processing of Written Language

- Chapter 11 Speech Perception and Modularity: Evidence from Aphasia

- Chapter 12 The Neurofunctional Modularity of Cognitive Skills: Evidence from Japanese Alexia and Polyglot Aphasia

- Author Index

- Subject Index