eBook - ePub

Treatment Outcomes In Psychotherapy And Psychiatric Interventions

Len Sperry, Peter L. Brill, Kenneth I. Howard, Grant R. Grissom, Len Sperry, Peter L. Brill, Kenneth I. Howard, Grant R. Grissom

This is a test

Share book

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Treatment Outcomes In Psychotherapy And Psychiatric Interventions

Len Sperry, Peter L. Brill, Kenneth I. Howard, Grant R. Grissom, Len Sperry, Peter L. Brill, Kenneth I. Howard, Grant R. Grissom

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Published in 1996, Treatment Outcomes in Psychotherapy and Psychiatric Interventions is a valuable contribution to the field of Psychiatry/Clinical Psychology

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Treatment Outcomes In Psychotherapy And Psychiatric Interventions an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Treatment Outcomes In Psychotherapy And Psychiatric Interventions by Len Sperry, Peter L. Brill, Kenneth I. Howard, Grant R. Grissom, Len Sperry, Peter L. Brill, Kenneth I. Howard, Grant R. Grissom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Psicoterapia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Paradigm Shift in Treatment Outcomes

1

From Outcomes Measurement to Outcomes Management

Mental health treatment is entering a new era. There is increasing emphasis on quality and accountability of mental health treatments based on outcomes measurement. In this chapter, we describe how the changing health care scene will force competition based on value. Next we discuss why demonstration of value to payers requires the use of outcome information. However, measuring outcome is not easy. There are many clinical and practical problems to be overcome. We describe an approach to the solution of these problems. We then highlight the evolution of three phases of the use of outcomes information: measurement, monitoring, and management systems. Last, we discuss what we believe will be the ultimate solution to the complexity of documenting and improving treatment, which we label the predictive system.

The Mental Health Environment

Over the past two decades, the enormous increase in health care expenditures has become a major issue confronting U.S. policy makers and business leaders. Spending on health care has been growing faster than the economy, rising from 8% to 14% of gross domestic product from 1975 to the early 1990s. Mental health care costs have grown even faster—doubling from $150 per employee to over $300 between 1987 and 1992.

One of the main forces pushing up the cost of mental health care is the increasing demand for services among employees. Frequent downsizings by corporate employers trying to become more competitive have raised stress levels of American workers, whether they are the ones laid off or those who have remained on the job, shouldering greater responsibilities and putting in longer hours. Mean-while, traditional institutions such as the family are no longer offering the support systems that they once provided.

In the Business and Industry Needs Assessment survey (developed by Integra, Inc., 1992), nearly half of 8000 employees tested in 35 organizations were shown to be experiencing behavioral problems. This survey, which was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, measured 12 behaviors, including work stress, job impairment from alcohol and other drug use, work dissatisfaction, anxiety, and depression. Over 47% of employees in the survey were found to be suffering from one of these five problems, with almost 13% of the survey participants suffering from two or more. Results showed 21% of employees experiencing high stress and 18% meeting the criteria for high anxiety, with 11.5% to 12.5% shown to be problem drinkers. Indeed, a major factor accounting for the increase in mental health care costs has been the rise in inpatient treatment for alcohol and drug abuse.

When Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs) were instituted, providing for a fixed payment by diagnosis, psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses were not included. For the rest of medicine, DRGs ended the cost-plus era (i.e., the era in which the more that was spent, the more the hospital was reimbursed). DRGs worked to keep costs down and tended to limit the profitability of inpatient facilities. However, since psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses were excluded, insurance companies continued to reimburse hospitals for their per diem costs and doctors for patient visits, no matter what they charged. With the rest of medicine controlled by DRGs, an opportunity now existed in mental health and substance abuse that resulted in the rapid growth of inpatient treatment. As a result, inpatient costs sky-rocketed, rapidly pushing up the percentage of the medical dollar spent on mental health. Indeed, in many corporations it rose from under 8% to higher than 20% of all medical expenses.

At the same time, state legislatures began to license more and more mental health professionals, which included social workers, marriage and family counselors, and nurses. Insurance companies reimbursed these professionals, who seemed to offer a cheaper alternative to treatment than did doctoral level psychologists and psychiatrists. This was intended to hold down reimbursement costs but instead, the demand for treatment accelerated and with it, the costs.

Finally, some states began to pass laws mandating coverage of substance abuse and in some cases making it equal to other medical conditions. This additional coverage, coupled with an enormous need for substance abuse treatment, rapidly accelerated the growth of costs in this area.

In the past, corporations assumed a relatively passive attitude toward these rising costs, relying on indemnity insurance, which paid for therapy sessions and other services on a cost-plus basis. But as costs continued to escalate and corporations found themselves under increasing financial pressure, they began the search for cost-containment plans.

This presented an opportunity for managed care companies and led to the entry of HMOs and carve-out firms into the mental health field. Initially, these firms concentrated on reducing inpatient health care costs by using a variety of approaches to case management. Through utilization review, they began to challenge providers who were recommending continued treatment for some of their patients, especially those who had been in long-term therapy. Through managed access, HMOs and carve-out firms (firms that contract to provide mental health services separate from other medical services) established barriers that made it more difficult for patients to obtain care—for example, patients were required to receive permission from a case manager before visiting a clinician. The managed care companies also tried to contain costs by altering benefits— raising copayments and deductibles, and so on.

Next, managed care companies developed networks of clinicians who discounted their fees. This was made easy because of the over-supply of providers. However, managed care firms feared that clinicians would make up for the drop in income per session by extending the number of sessions. Therefore, the managed care organizations began to profile providers on their average number of sessions per case and on whether they were “managed care friendly.” What did this mean? Sessions per case translates into dollars per case. If a provider used “too many” dollars per case on the average, he or she would be dropped from the network. “Managed care friendly” meant such things as whether the clinician too often argued with the managed care firm over the number of sessions. The power had clearly shifted to the managed care firm, which could reduce care by simply saying “No.” Some carve-out managed care firms did little to limit outpatient care except to ask clinicians to provide long treatment summaries, which deterred them from requesting more sessions. Other firms simply allowed for very few sessions on the average. Unfortunately, no objective measures of quality counterbalanced these cost reduction measures. There was no universally accepted or scientifically sound method of determining how much of what type of care was needed.

Many managed care contracts were initially for administrative services only. There was no additional compensation to these firms if they saved the employer money and no risk if they overspent in authorizing care. Gradually, at-risk arrangements began to develop and capitation rates became the standard in the managed health care field. HMOs and carve-out firms now found themselves required to provide adequate levels of care to patients for fixed annual fees set by the payers, with enough money left to pay overhead expenses and make a reasonable profit.

Meanwhile, capitation rates kept going lower and lower, under pressure from large corporations as well as from partnerships between corporations and insurers who were trying to drive down costs. With all the competing HMOs and carve-out firms in the field, mental health care had gradually become a commodity, driven by price. Since price was the only element that could be measured at that time, it was also the only one that would be rewarded. As yet, there were no adequate measures for other elements of care, such as rates of patient improvement or cost-effectiveness.

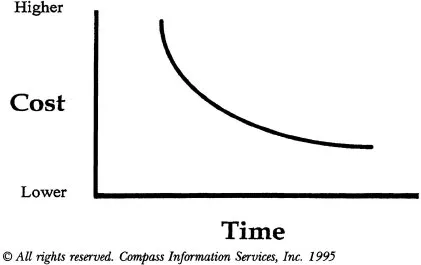

Managed care firms and provider networks found themselves operating in a new environment, and many of them began to fear that they would eventually be driven out of business as capitation rates continued to go lower and lower (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Competition Will Derive Capitation Down

Price cannot be the only driver. Among gasoline stations, for example, only 20% of customers have been shown to make purchases solely on the basis of price (IBH Keynote Address, 1995). Other factors include the location of the station, how well-lighted it is, cleanliness, or whether it has a convenience store. Customers make buying decisions based on perceived value. To a certain extent, the concept of perceived value can be determined only in a circular fashion. Features such as the location of a station, for instance, are thought to have value because they persuade customers to buy, or to buy at a higher price.

These same forces have begun working in the managed mental health care field. Today, many companies are looking for ways not only to reduce costs but also to maintain or improve quality of care—in short, achieve value for their health care dollar. Value in mental health care is a very tricky concept. The first essential question is: Value to whom? Value may mean different things to the patient, his family, the clinician, the corporation, the community, the government, and society at large. Each may represent a different constituency that perceives very different values from different aspects of mental health care. For example, when a family has a member who is suicidal, the fact that a treatment site is open 24 hours per day may be of enormous value. On the other hand, the community may place a high value on treating substance abuse patients who have been involved in thefts. Value as perceived in the present may beg the question of how a decision made today may impact the future. For instance, failure to receive two extra sessions of treatment this month may result in long-term disability in the future.

The complexity of the value problem initially caused payers to shrink from making any differentiation in terms of clinical quality and to simply make purchases based on price. However, the benefits managers of many companies became dissatisfied with the performance of their current managed care vendors and decided to reenter the market to find a more effective approach. These managers began to grasp that while the determination of values and clinical quality is complex, it cannot be ignored simply because of its complexity.

For example, the benefits manager at one large steel company decided to sever a three-year relationship with a managed care firm after receiving a substantial number of complaints from employees about the quality of care. He wanted greater consistency of treatment and more accountability, not just lower costs. At a major pharmaceutical company, the director of corporate benefits recognized that the only way to cut costs without reducing the quality of care was by the “efficiencies offered by carefully monitoring the results of treatment.”

More and more employers are looking for an effective approach to achieving cost-effectiveness by monitoring outcomes in mental health care treatment. This would also offer managed care companies an opportunity to compete on the basis of quality as well as cost. But finding accurate measurement tools to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment has proven to be extremely difficult.

One reason is the complex mix of levels and types of care, as well as of diagnoses. Due to the stringent efforts of managed care companies, inpatient hospital stays have been reduced and the resulting costs substantially lowered. However, inpatient care has often been replaced by a more complicated matrix of treatments. This includes: (1) different levels of care—ranging from residential, to full- and part-time day care, to regular outpatient sessions with a clinician; (2) different types of care, such as individual or group therapy, medication, or shock therapy; and (3) an entire range of illnesses that these treatments are supposed to alleviate. How can anyone managing this kind of mental health system measure the cost-effectiveness of a particular treatment for a particular patient? There appear to be far too many variables.

For example, should patient A receive individual therapy combined with medication in addition to full-time day hospital treatment? It would be cheaper to move him into partial day care and group therapy. But how do we measure the impact of these changes on the patient? If the change in treatment didn’t work, was it the partial day care or the group therapy or both that were not helping? What’s more, which measurements are we using to determine whether the patient is getting better or worse? And are these measurements valid?

Thus, determining cost-effectiveness is extremely complex. But in the absence of any valid measurements, managed care companies were faced with the dismal prospect of continuing to compete only on cost. Some of these companies even tried to reduce costs further by buying up networks of providers, setting standards for them, and subcapitating. Meanwhile, provider groups had been attempting to deal with capitation through vertical and horizontal integration to prevent cost shifting (e.g., from outpatient to inpatient). Eventually, the provider groups began to recognize that they could eliminate the managed care companies and deal directly with payers themselves. However, whether it is a managed care company trying to cut costs by passing on a subcapitation rate to a provider group or a provider group contracting directly with a payer, the problem is the same: Will all the competition be solely on the basis of price, or will it be on value?

One final note about organizations that compete solely on price: When price is the only basis of competition, then the pressure to decrease profits is relentless. A buyer constantly tries to shop the cheapest price, which drives down the organization’s profits. However, when an organization competes on value, then profit margins are not as subject to a profit squeeze. The purchaser is then making a decision to buy on value and not necessarily pushing an organization’s profits downward.

The problem remains though, that to compete on clinical value, a method of determining clinical quality must be found that is accurate and accepted by the field. To better understand this, one must appreciate outcomes research and its evolution.

Evolution of Outcomes Research

Traditionally, providers and managed care companies have measured the quality of their programs by three different methods: structure, process, and patient satisfaction. Structure refers to the elements of the mental health treatment program, the credentials of its providers, and whether they are sufficient to provide the services offered. For example, does the program provide substance abuse treatment, or is there a medical doctor on staff to administer medications? While a patient may be unable to receive the necessary treatment unless a program has the proper structure, there is no proof that these structural elements are directly related to the patient’s improvement. Thus, the patient may be prescribed a specific medication, but it may not be treating his illness effectively.

The second criterion for measuring the quality of a program has been how well its processes are executed. For instance, how many rings of the telephone occur before an intake employee answers it? How long does it take from the time of referral to the time a patient receives an appointment with a provider? Clearly, these things are important. After all, a patient may feel more satisfied if he has rapid access to care, and certainly he cannot receive care without this access. However, there is no proof that the rapidity of access has any impact on the outcome of treatment.

The third measurement of quality has been patient satisfaction. This includes such measures as how well the patient thought she was treated by the therapist and how mu...