![]()

1

The Regular Grid as Historical Object

"Geometry is the means, created by ourselves, whereby we perceive the external world and express the world within us. Geometry is the foundation."

- Le Corbusier

This chapter briefly reviews the history of regular grid planning in human settlements before the 19th century with an emphasis on when and where. The objective is to establish at a basic level how regular grid town planning in other parts of the world and different periods of history influenced its eventual application in the American context. This includes early influences most commonly cited by historians in giving shape to the American urban landscape such as the Spanish Laws of the Indies, medieval European bastides (i.e. fortified towns), Thomas Jefferson's Land Ordinance of 1785, and William Penn's 1682 plan for Philadelphia. The chapter argues the regular grid has been a standard part of the town planning vocabulary for more than 4,500 years. There is evidence for the emergence of distinctive and separate traditions of regular grid planning in the Indus Valley Civilization of Ancient India and Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Some argue for distinct, separate traditions in Ancient Egypt, Greece, Italy, and the Orient, but the evidence is inconclusive. The emergence of regular grid planning traditions in Ancient India and Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica indicates the generic qualities of the regular grid as an artifact of physical arrangement - that is, as a general consequence to the act of humans placing dwellings in a settlement - is a contributory factor for its widespread use in so many settlements around the world. The chapter concludes by arguing the importance of William Penn's 1682 plan for Philadelphia on the American town planning tradition lies in its size, not its composition. Penn's plan demonstrated town planning could occur on a previously unimaginable scale in the abundant lands of the New World.

From Ancient India to the Roman Empire

The regular grid has been a standard part of the town planning vocabulary in human settlements for more than 4,500 years. Some suggest its arrival in the New World is an example of historical diffusion, which is the sequential influence of (or cultural transmission from) one society to another, which can be reliably traced over time and space. Stanislawski (1946) argues "despite its apparent obviousness, it would seem (the regular grid) was not put into practice by any except those who had known it previously or who had access to regions of its occurrence" (112-113). According to Stanislawski (1946), regular grid town planning first originated in Ancient India, diffusing in a well-defined manner over time along trade routes to Assyria, then Greece and Rome, Western Europe, and eventually into the New World. According to Reps (1965), the use of the regular grid in the New World was more due to "functional requirements rather than historical imitation" (2). Stanislawski (1946) and Kostof (1991) trace the earliest example of regular grid town planning in the world to the Indus Valley Civilization of Ancient India, specifically the city of Mohenjo-Daro located in modern day Pakistan approximately 2,500 years before the birth of Christ.1 According to archaeologists, Mohenjo-Daro probably had around 35,000 residents at its height (Kenoyer, 1998).

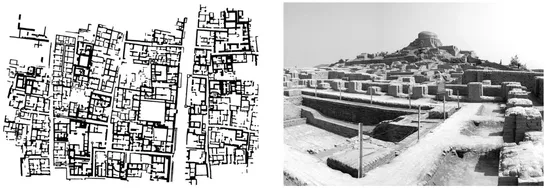

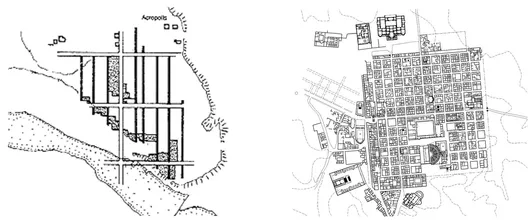

Figure 1.1 - Ancient India: (left) excavated plan of Lower Town in the city of Mohenjo-Daro founded circa 2,500 BC in modern day Pakistan (Image: © 2017, Trustees of the British Museum); and, (right) excavated remains at the Mohenjo-Daro UNESCO World Heritage Site.

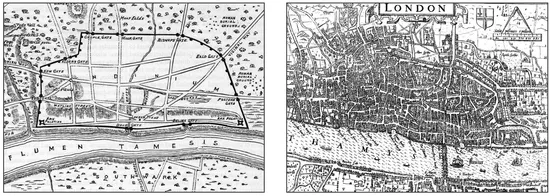

Figure 1.2 - The Transformation of London: (left) Roman London after 62 AD (various sources are cited for the creation of this plan but it should be considered illustrative and not factual); and, (right) Norden's 1593 map of the City of London.

The excavated plan of Lower Town in Mohenjo-Daro appears only suggestive of an underlying geometrical logic to its layout. However, the vertical dimension of its archaeological remains makes the geometric foundations of the city layout more readily apparent (Figure 1.1). It is likely a process of building and rebuilding in the city over a thousand years of habitation caused the plan to deviate from its initial geometric logic. This is quite common. Rossi (1982) describes this as the urban dynamics of "destruction and demolition, expropriation and rapid changes" (22). The City of London provides an excellent example of this process at work. The Romans founded the City of London (Londinium) as a civilian settlement based on a regular grid circa 50 AD (Wacher, 1974).2 As building and rebuilding occurred in the city over time, the plan of London took on the characteristics of a deformed grid (Figure 1.2).

Others point out the Egyptians were using orthogonal grid planning for the city of Kahun in the Old Kingdom around 3000-2500 BC (Fairman, 1949; Gallion and Eisner, 1963; Mumford, 1961; Owens, 1991). However, more accurate archaeological dating indicates Kahun (originally named Hotep-Senwosret or "Senwosret is Satisfied") was built in the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom during the reign of Pharaoh Senusret II (also known as Senwosret II or Sesostris II) from 1897 to 1878 BC. Kahun was a city built for administrators, priests, artisans, and workers assigned to construct the Pyramid at El-Lahun and maintain the funerary cult of Senusret II after his death.3 The streets of Kahun were aligned to the cardinal points of the compass and the pyramid complex of Senusret II (Figure 1.3, left)(Badawy, 1966; Kemp, 1989). While Stanislawski's (1946) hypothesis of regular grid town planning principles diffusing along trade routes from Asia to the Near East and then presumably to Egypt cannot be entirely discounted, it would also not be surprising if a separate tradition of regular grid town planning arose in Ancient Egypt. The earliest Egyptian pyramid (Pyramid of Djoser designed by the architect Imhotep) was constructed around 2630-2611 BC, or about the same time as the founding of Mohenjo-Daro in Ancient India. Others have documented the skill and precision of Ancient Egyptian surveying techniques, some of which endured in practice into the early 20th century (Rossi, 2004). Because of this, historians cannot reliably discount the emergence of a separate tradition of regular grid town planning in Ancient Egypt.

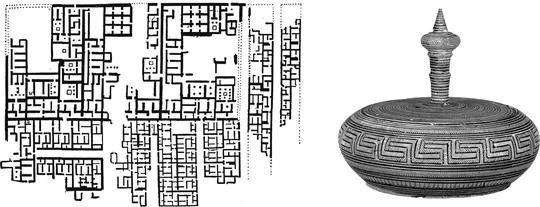

Figure 1.3 - (left) Orthogonal layout in the city of Kahun during the 12th Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom in Ancient Egypt circa 1,900 BC; and, (right) Geometric Period Greek Pyxis (box with lid) in terracotta, mid-8th century BC.

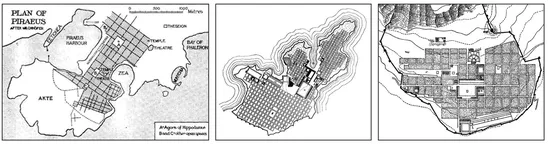

Stanislawski (1946) provides an illuminating review about the history of regular grid town planning, beginning in Mohenjo-Daro, then to Assyria with the founding of the new capital at Magganuba in the 8th century BC, and the eventual introduction of the regular grid in the Mediterranean Basin. The Ancient Greeks made widespread use of the regular grid in town planning activities during the Hellenic or Classical Period from 500 to 300 BC (Stanislawski, 1946; Gallion and Eisner, 1963; Rykwert, 1988). Some historians credit Hippodamus, a 5th century Greek, with 'invention of the orthogonal grid system (Stanislawski, 1946; Rykwert, 1988; Owens, 1991). However, this is a fallacy since there is ample evidence for regular grid town planning at least two millennia before its widespread application in the Mediterranean Basin. According to Gallion and Eisner (1963), it is not even accurate to suggest Hippodamus was responsible for its reemergence during the Hellenic period. The rebuilding of Greek cities destroyed by the Persians near the end of the Archaic Period (800-500 BC) utilized the orthogonal grid system. Finally, Greek art during the Homeric or Dark Age (1100-800 BC) is commonly characterized by geometric motifs in vase painting (i.e. Geometric Period). At the very least, it indicates the Greeks were adept at handling geometrical concepts almost 400 years before the life of Hippodamus (Figure 1.3, right on previous page). The best surviving record of Hippodamus comes from Aristotle, who credits him with planning Piraeus, the port town of Athens. This is probably the only plan that can be reliably attributed to him (Owens, 1991). It was possible he was involved in the planning of the Greek town Miletus (Miletos) in Anatolia (modern day Turkey) circa 479 BC. However, Owens (1991) argues this is pure conjecture. Several historians suggest 5th century BC is when the regular grid began to become a standard part of the town planning vocabulary. Owens (1991) states, "Hippodamian gridded cities... were a widespread feature of the Greco-Roman world" (6). This was due, in no small part, to the expansive military conquests and town-founding activities of Alexander the Great from his ascension to the Macedonian throne in 336 BC to his death at Babylon in 323 BC

Figure 1.4 - Greek Town Planning: (left) speculative illustration of Hippodamus' plan for the Athenian port town of Piraeus; (middle) Hippodamian orthogonal grid in Miletus (Miletos) on the western Aegean coast of Anatolia (modern day Turkey) circa 479 BC; and, (right) orthogonal grid in the Alexandrian city of Priene on the western Aegean coast of Anatolia (modern day Turkey) circa 323 BC.

Figure 1.5 - Town Planning in Ancient Italy: (left) 6th century Etruscan town plan of Marzabotto in the Po Valley of Northern Italy; and, (right) town plan of Timgad (Thamugadi) founded in North Africa during the reign of Trajan around 100 AD.

(Stanislawski, 1946; Gallion and Eisner, 1963; Rykwert, 1988; Owens, 1991). Stanislawski (1946) offers the Alexandrian city of Priene as probably the best example of Greek regular grid town planning (Figure 1.4).

Stanislawski (1946) argues the Roman version of the regular grid is a transformation of the Greek model, coopted primarily for military purposes. Owens (1991) comments on this, stating, "the Romans introduced new ideas which were adapted to their standardized, but nonetheless flexible, approach to town planning" (120). However, some argue for a separate tradition emerging with the Etruscans during the 6th century BC in Italy (Owens, 1991). If true, this might mean the generic nature of the regular grid for the physical arrangement of space was self-evident to the Etruscans instead of culturally transmitted from the Greeks via the Etruscans to the Romans. However, Owens (1991) goes on to assert the more likely explanation is the Greeks influenced the Etruscans, given the extent of Greek colonization efforts throughout the Mediterranean Basin including southern France and Italy beginning around 800 BC. According to Owens (1991), "axial grid planning became the characteristic feature of Roman colonies and towns through Italy... undoubtedly built upon the achievements of the Greeks and Etruscans... the combination of adaptability within a standardized arrangement laid the foundations for the urbanization of the Roman Empire in succeeding centuries" (118-120). The best surviving example of Roman regular grid town planning is probably Timgad (Thamugas or Thamugadi). It was a military camp established during the reign of Emperor Trajan circa 100 AD and located in modern day Algeria (Figure 1.5).

From Medieval Europe to Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica

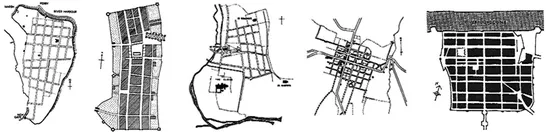

Figure 1.6 - Medieval planned towns: (from left to right) New Winchelsea, Sussex, England; Beaumont de Périgord, France; New Salisbury, Wiltshire, England; Ste. Foy la Grande, Gironde, France; and, St. Denis, Aude, France.

Stanislawski (1946) argues the time from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD until the late medieval period circa 1200 AD represents a period of disuse for regular grid town planning, He argues this was due to the decline of centralized political power in Europe. He sees the reemergence of regular grid town planning during the 13th century in Europe as a natural consequence to the reemergence of centralized political power in the form of absolute monarchy. A large number of planned towns used the regular grid during the late medieval period (Lilly, 1998). The most comprehensive review of town planning during this period is Maurice Beresford's New Towns of the Middle Ages: Town Plantation in England, Wales and Gascony (Beresford, 1967). He identifies 97 towns with surviving evidence of a regular grid layout. Of these: 26 are located in England including Liverpool; 26 in Wales including Cardiff; and, 45 in western Normandy of northern France. Beresford (1967) points out most of these towns were military or commercial bastides, each having "their own variation on the theme of rectangularity" and often with a central market square in the plan (10). He suggests the use of the regular grid for these medieval bastides was because the plan "was a flexible one. It could be adapted to a square site as well as a long, narrow site; rectangles of different size could be laid together to cover hill sites such as Monségur or Dommen where the natural features did not leave a neat rectangular level space" (Beresford, 1967; 147) (Figure 1.6).

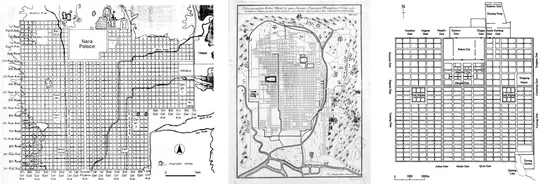

Several historians also point out there was a regular grid planning tradition in the Orient and Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Kostof (1991) cites the orthogonal grid layout in the Japanese city of Heijokyo (present day Nara) founded in 710 AD. Moholy-Nagy (1968) reviews some other examples including the royal city of Kyoto, Japan founded circa 792 AD by Emperor Kammu and Ch'ang-an in China founded during the Han Dynasty circa 195 BC (Figure 1.7). Like others, Moholy-Nagy (1968) views the regular grid planning tradition in the Orient as further evidence for the cultural expression of centralized military/political power and control. It is unclear if these Orient examples truly represent a separate tradition from the one emerging at least two millennia earlier in the Indus Valley Civilization of Ancient India (Major, 2015a).

Figure 1.7 - Oriental regular grids: (left) Heijokyo (contemporary Nara, Japan) founded in 710 AD; (middle) Royal city of Kyoto, Japan founded circa 792 AD; and, (right) Ch'ang-an in China founded during the Han Dynasty circa 195 BC.

In Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, Kubler (1993) points to the 'native grids' of the Aztec city Tenochtitlán founded circa 1325 AD and Olmec city Cholula founded circa 600-700 AD. Both Tenochtitlán and Cholula were located in present day Mexico. Mesoamerica is a term referring to a region of the Americas that extends approximately from central Mexico to Bel...