![]()

1

The Individual and Organizational Sides of Personnel Selection and Assessment

Heinz Schuler

Universität Hohenheim

Stuttgart, Germany

James L. Farr

Pennsylvania State University

Mike Smith

University of Manchester

United Kingdom

In many areas of their professional interests, industrial and organizational psychologists are used to taking both sides of a problem into consideration—the organizational side and the individual side. When it comes to personnel selection, however, they seldom optimize more than cost-benefit relationships for the organization. The principle of giving open and accurate information to all involved individuals is canceled, in this way preserving the competitive character of the selection situation.

Porter, Lawler, and Hackman (1975) wrote:

The ideal situation would look quite different from the one which typically exists. The organization would describe the job it has to offer in realistic terms, pointing out both the satisfactions and the frustrations that the job presents. It might present the results of job attitude surveys carried out with people in the job. If relevant, the individual might be given a chance to interview job holders. Tests would be administered and the individual would be presented with results to help him decide whether he wants the job. He would be told how likely people with his scores are to succeed on the job. The individual, on the other hand, would present as accurate a picture of himself as he could. He would talk openly about his strengths and weaknesses, and he would respond to selection instruments as candidly as possible, (p. 157 f.)

This field of activities being questioned so radically is what 40% of the articles in the four main journals of our discipline deal with (Cooper & Robertson, 1986)—personnel selection and assessment. Many advances have been made in personnel selection within the last 15 years or so. But all these advances lie in the “technical” (psychometric) or organizational (economic) side of the process. Only a few research studies, on the other hand, have been devoted to the individual side or to the interaction of both perspectives, although there are multiple reasons for such research and its reflection in practice.

Despite many demonstrations of selection utility (Boudreau, 1989), in large segments of the public a critical attitude toward methods of personnel psychology has taken place. In the United States, the ongoing discussion of test fairness demonstrates that reduction of procedural justice to statistical terms is not accepted by many who conceive it rather as a social–political problem.

In most European countries, fairness is not as prominent an issue as in the United States, but there has been a critical attitude against personnel selection, and especially against psychological tests, common in the last two decades. Among the aspects of this critique are:

- Selection is only in the interest of the organization.

- Selection is an untimely expression of differences in social power: Applicants are forced to undergo procedures arbitrarily imposed on them if they do not want to lose their chance to get the job.

- Selection and assessment situations are nontransparent, that is, candidates are not given the relevant information about what is measured and what conclusions are made.

- Selection and assessment is stressful to the candidate.

In many cases, this critique or skepticism is not openly uttered but is hidden behind or enforced by the argument that selection methods are invalid. It reflects changing societal values—a changing attitude toward science, demanding legitimization of scientifically based technology; skepticism against secret lore and growing requests for transparency or openness of methods and decision principles; and sensitization toward invasions of privacy and fear of misuse of personal data.

Criticism of this kind seldom found its counterpart in a systematic, theoretically based, and empirically convincing argument. Certainly, we do know reasons for individuals to deal with selection in a constructive way (e.g., to get information about job requirements, to gain a realistic view of own competencies and potentials, to avoid excessive demands—over or underload, or to profit from the advantage that working for an organization with an efficient (high-utility) selection system should be more competitive and thus provide a more secure and socially recognized employment setting).

Needless to say, for the organization there are also reasons to consider the individual’s perspective. For example, the organization with a selection system that is viewed as valid and fair may find it easier to recruit qualified applicants; knowing which kind of information reduces later turnover of qualified people is of high value, the changing labor market making these aspects even more important; and not disturbing a positive organizational climate by an unacceptable system of performance assessment. But, beyond utility calculation, there is also an ethical dimension in treating applicants and employees in the same responsible and humane manner that is characteristic of most other psychological practices in organizations (i.e., requirements to pursue fair and considerate principles and procedures in selection and assessment).

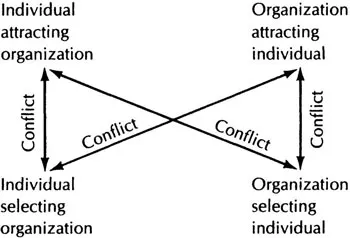

Porter, Lawler, and Hackman (1975) suggested a heuristic that makes plausible the advantages that exist for organizations as well as for individuals to consider the other’s perspective. They present an attraction-selection framework in which individuals and organizations are both attempting to attract the other and to select from those attracted to them (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. The attraction-selection situation (from Porter, L. W., Lawler, E. E. III, & Hackman, J. R. (1975). Behavior in organizations. New York: McGraw- Hill, Inc. Reprinted with permission.

From the individual’s point of view, the selection process is not simply a matter of choosing a job in a given organization and gathering relevant information; the individual is, at the same time, interested to behave in such a way that will lead the organization to offer him or her a job. These intentions may get in conflict (e.g., asking some questions applicants are interested in may lower their chance to get a job offer).

The same is true for the organization. The selection process may attract potential employees, but it may also stand in contrast to the goal of attraction and repel the most qualified individuals. Especially if a low selection rate is intended, the effect may be to frustrate even a large number of qualified persons and result in unexpected effects for the organization’s image.

A separate and almost ubiquitous kind of conflict for both of the contracting parties lies in the intention to be attractive to the other party. So, an individual’s desire to attract the organization may lead to a kind of impression management that lowers the validity of the personnel decision. Or, the organization’s desire to attract individuals by addressing their assumed occupational desires may stand in contrast to the individuals’ interest to optimally choose an organization.

Of the four parameters of the Porter et al. model, only the selection of individuals by the organization is researched intensively. This is not true for the other three components, let alone the interactions (i.e., the conflicts among these goals). Although there is a vast amount of knowledge from basic research in different psychological disciplines that could be utilized, there is not even sufficient data at hand to support premises we have been relying on for decades. For example, the argument that rational selection is also in the interest of the individual as it protects the ill-suited applicant from potential stress or underutilization was forwarded by Münsterberg (1912), but although there are some indirect indicators for this, there are no studies to investigate this relationship directly. As long as we do not define and measure well-being indicators as validation criteria, our arguments can be viewed as being one-sided in favor of the organization.

Whether or not Porter, Lawler, and Hackman’s (1975) vision of selection as a perfectly cooperative effort has a chance to be realized is open to question. Frustration of applicants can hardly be avoided if there are more qualified applicants than job openings, and the organization’s interest in selecting the highest ranking person among them in many cases will lead to a conflict of interest. Furthermore, Porter et al. seem to take for granted that each rejected applicant can find a better fitting job. Among other things, our knowledge from validity generalization (Schmidt & Hunter, 1981) makes these assumptions questionable even in times of a labor market favoring applicants.

Consequently, this approach, taken literally, will be realistic only in a situation where at least one of the interaction partners is in a neutral position (e.g., the consultant in occupational counseling as it is institutionalized in the German Office of Labor). But there should also be possibilities to reach the goal to behave cooperatively at least partly or in essential components in organizational assessment and selection. Crucial for this is a better knowledge of participants’ perceptions of and reactions to selection and assessment situations and of the relationships between individual and organizational perspectives.

This is the content of this volume. The authors of the following chapters summarize research and some theory related to this field and report recent investigations of special topics. The first section is devoted to individual perceptions. Included are chapters that describe how individuals—mostly applicants, but also representatives of the organization and others—perceive different selection methods and procedures; which parameters of assessment and selection situations have been shown or can further be expected to influence perceptions of the methods, of the persons acting, and of the organizations; and what can be done to improve those impressions.

The second section deals with individual reactions to personnel procedures, including job analysis, selection, assessment, and feedback. Although there is a certain body of research on motivational distortion in selection situations (which is represented here by an extensive study on personality questionnaires), there is less information on individual differences in responding to job analyses and job evaluations. In both cases, it may be useful to recognize and take into account such tendencies. Other contributions report emotional and cognitive reactions to selection situations (e.g., individual differences in stress and coping, and effects on participant’s self-esteem). Two chapters on performance evaluation and feedback report that there are a number of factors determining reactions to appraisal. Most chapters in this section try to give advice for improving selection and assessment situations in regard to individual reactions. This is especially true for one chapter that takes pain to improve newcomer orientation programs by learning from patient preparation programs for medical operations.

In the third section individual and organizational perspectives are considered in a wider social context. Fairness is discussed in its different aspects and changing conceptions. According to different relevant issues in public policy, fairness turns out to have a different status in the United States and in Europe. The changing role of the psychologist in personnel selection is reflected in a review covering the last two decades, and some standard procedures in selection as well as in performance appraisal are questioned in favor of new orientations.

The last section includes a sample of contemporary approaches to selection and assessment. Computer-assisted assessment is one of the major trends in personnel selection, and an overview is given of the major steps and implications of automating assessment procedures from selecting an instrument to final decision making. Another chapter presents an approach that makes use of the special possibilities of personal computers in order to implement principally new task or test concepts in complex problem solving. Possibilities, but also problems, of planning and decision making in computer-simulated scenarios are discussed. A longitudinal study reports relationships between aptitude measures and self-report data on the one hand and occupational choice and satisfaction on the other hand. The final chapter offers evidence whether fairness of assessment center ratings is restricted by group composition effects.

References

Boudreau, J. W. (1989). Selection utility analysis: A review and agenda for future research. In M. Smith & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), Advances in selection and assessment (pp. 227–257). New York: Wiley.

Cooper, C. L., & Robertson, I. T. (1986). Editorial foreword. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology 1986 (pp. ix–xi). Chichester: Wiley.

Münsterberg, H. (1912). Psychologie und Wirtschaftsleben. Leipzig: Barth.

Porter, L. W., Lawler, E. E., III, & Hackman, J. R. (1975). Behavior in organizations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (1981). Employment testing: Old theories and new research findings. American Psychologist, 36, 1128–1137.

![]()

I

Individual Perceptions of Personnel Procedures: Introductory Comments

It is logical to start a book on the Individual and Organizational Perspectives of Selection and Assessment with a section on Perception. Unless the individual perceives the selection process, he or she can have no views or reactions to it—the perceptions form the basis for subsequent psychological processes. If the perceptions are positive, it augers well for latter stages such as commitment, participation, and acceptance. If the perceptions are negative, the prognosis is poor and there is a clear danger that the selection process will end in failure because the individual breaks the chain of events that could lead to his or her engagement by the company.

This section brings together four chapters focused on the perceptions of job candidates. These chapters have a great deal in common. For example, they all provide data on what candidates think about various selection methods, such as interviews, and they all report data on attitudes toward selection devices. However, they tackle this task in quite different ways so that the section as a whole gives a very rounded picture.

The first chapter by Heinz Schuler is u...