![]()

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION TO THE IRANIAN LANGUAGES

Gernot Windfuhr

1 OVERVIEW

The Iranian languages constitute the western group of the larger Indo-Iranian family which represents a major eastern branch of the Indo-European languages. With an estimated 150 to 200 million native speakers, the Iranian languages are one of the world’s major language families. The present volume thus relates linguistically most closely to four other volumes in the Language Family Series: genetically to The Indo-European Languages and The Indo-Aryan Languages, areally to the latter as well as to The Turkic Languages and The Semitic Languages, and typologically to all four of them due to adjacency and partial symbiosis.

Following an overview of the typology of the Iranian languages and selected topics, this volume provides detailed descriptions of principle Iranian languages from Old Iranian to New Iranian. In terms of descriptive orientation, it aims to present the typological dynamics of the Iranian languages through time and space. In terms of coverage, each chapter addresses issues on all linguistic levels including not only an overview, writing systems, phonology and morphology, but also phrase, clause, and sentence level syntax, and pragmatic aspects, which are all documented by examples with close interlinear translations and comments. That is, the overriding focus is on how these languages “work”, highlighting on each level significant typological features. As such, the volume is complementary to the Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum (1989), edited by Rüdiger Schmitt (see CLI in the List of Abbreviations, I.), which, with its focus on the phonological and morphological levels, will stand as the standard reference work for many years to come. In fact, several contributors to the present volume also contributed to the Compendium (Skjærvø, Emmerick, Windfuhr, Kieffer).

The orientation towards typology reflects the appearance of an increasing number of publications on Iranian typology and linguistic universals on all levels, which necessarily encompass diachrony and diatopy, by a growing group of specialists in Iranian linguistics and of general linguistics working on Iranian languages, an orientation originally spear-headed, among others, by Joy I. Edelman (e.g. 1968). Also, comprehensive studies of individual Iranian languages and language groups have been published, a good number of them by contributors to this volume, and comprehensive series on Iranian languages have appeared, such as the two volumes of the Opyt istoriko-tipologicheskogo issledovaniia iranskikh iazykov (1975), the six volumes of the Osnovy iranskogo iazykoznaniia(1979–1997), both edited by Vera S. Rastorgueva, and the three volumes dedicated to Iranian languages of the Iazyki mira. Iranskie iazyki (1997–2000), edited by Andrei Kibrik (for these see Opyt, Osnovy, Iazyki mira in the List of Abbreviations, I.). Two recent overviews of the Iranian languages and the symbiotic non-Iranian languages are Skjærvø (2006) and Windfuhr (2006), respectively.

This volume does not include descriptions of all Iranian languages, but only of 16 languages of the many, as representatives for the following characteristics: (1) the three historical stages of documentation, Old, Middle, and New Iranian; (2) the four main dialectological groups, North-West Iranian, South-West Iranian, East Iranian, and South-East Iranian; (3) geographical location. Specifically, modern South-West Iranian is represented by Persian and Tajik; North-West Iranian is represented by Zazaki, Kurdish, and Balochi; East Iranian is represented by Pashto, Shughni, and Wakhi; South-East Iranian is represented by Parachi. Geographically, Kurdish represents the (north)-westernmost expansion of the Iranian languages just as diametrically opposed Balochi represents their south-easternmost expansion, and the Pamir languages with Shughni and Wakhi represent the north-easternmost Iranian languages. Regrettably, Ossetic could not be included.

Overall, the coverage of languages in this volume can be seen as representing the center and the outer circle of Iranian, the latter in contact with non-Iranian languages and thus marked by Randsprachen as well as interference phenomena, anchored on two chapters: Chapter 3 on Old Iranian which represents the foundation of the Iranian languages, and Chapter 8 on Persian and Tajik which represents the superstrate language over the Iranian expanse and beyond, both as the literary language and through its regional varieties and vernaculars. Finally, in terms of morphological complexity, Persian represents the least inflectional language, while two languages represent the most highly inflectional languages: Zazaki among the West Iranian languages and morphologically even more complex Pashto among the East Iranian languages.

In terms of descriptive strategy, a number of chapters discuss closely related languages jointly and thereby highlight their comparative dynamics. These include: Avestan and Old Persian in Chapter 3 (Skjærvø); Middle Persian and Parthian in Chapter 4 (Skjærvø); Khotanese with Tumshuqese in Chapter 7 (Emmerick); Persian (Windfuhr) and Tajik (Perry) in Chapter 8. The dynamics of “Common” Balochi in relation to a great number of varieties, rather than an arbitrarily selected “Standard” one, is discussed in Chapter 11 (Jahani and Korn). Chapter 14a on the complex Sprachbund of the Pamir languages (Edelman and Dodykhudoeva) precedes the description of its dominant language, Shughni, in Chapter 14b (Edelman and Dodykhudoeva); Wakhan Wakhi and Hunza Wakhi are contrasted in Chapter 15 (Bashir). The other chapters, while focusing on individual languages, likewise provide notes on dialectology: Middle Iranian Sogdian in Chapter 5 (Yoshida) and Khwarezmian in Chapter 7 (Durkin-Meisterernst); Modern Iranian Zazaki in Chapter 9 (Paul); Kurdish in Chapter 10 (McCarus); Parachi in Chapter 12 (Kieffer); Pashto in Chapter 13 (Robson and Tegey).

Like the chapters on the Old and Middle Iranian languages, the chapters on the modern languages reflect the present state of research and are innovative in their detail, and specifically in their syntactic and typological coverage within the framework of a book chapter. A particular kind of innovation is the daring decision by the authors of the chapters on Sogdian and Khwarezmian to use phonemic transcription throughout in addition to transliteration.

Finally, not discussed in this volume are challenging recent studies that, with due caution, investigate the correlation of regional gene pools of contemporary populations with language groups and language shifts (rather than populations shifts) for which small elites are often sufficient, as shown for example in the study of the origin of the Kurdish- and Zazaki-speaking populations by Hennerbichler (forthc.).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edelman, D. I. (1968) Osnovnye voprosy lingvisticheskoi geografii. Na materiale indo-iranskikh iazykov (Fundamental problems of linguistic geography. Based on data of the Indo-Iranian languages), Moskva: Nauka.

Hennerbichler, F. (forthc.) Die Herkunft der Kurden, fully revised edition.

Skjærvø. P. O. (2006) ‘Iran vi. Iranian languages and scripts’, in EnIr 13.4, pp. 344–377 (additional parts forthcoming)

Windfuhr, G. (2006) ‘Iran vii. Non-Iranian languages,’ in EnIr 13.4, pp. 377–410.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

DIALECTOLOGY AND TOPICS

Gernot Windfuhr

1 INTRODUCTION

Today the Iranian languages are spoken from Central Turkey, Syria and Iraq in the west to Pakistan and the western edge of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China in the east. In the North, its outposts are Ossetic in the central Caucasus and Yaghnobi and Tajik Persian in Tajikistan in Central Asia, while in the South they are bounded by the Persian Gulf, except for the Kumzari enclave on the Masandam peninsula in Oman.

Historically, the New Iranian stage overlaps with the Islamization of Iranian-speaking lands in the seventh century CE. The Middle Iranian stage began in the third century BCE. The oldest stages go back to the beginning of the second millennium BCE. The oldest physical document of Iranian is the Old Persian inscription by Darius I. of 522 BCE on the rock face of Mt. Behistun near Kermanshah along the highway that leads down from the Iranian plateau into Mesopotamia.

1.1 Origins: The Central Asian component

For the following section, cf. also Windfuhr (2006b) and the Introduction to Chapter 3.

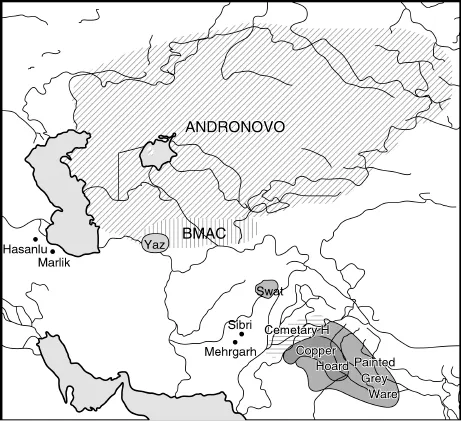

Research during recent decades suggests that the Proto-Indo-Iranians originated in the eastern European steppes (Pit-Grave culture, ca. 3500–2500 BCE). From there they apparently moved eastward to the southern Ural steppes and the Volga (Potapovo culture, 2500–1900 BCE), then further on to Central Asia (Andronovo culture, from 2200 BCE onwards). At that stage they appear to have already formed two groups: the Proto-Iranians in the north, and the Proto-Indo-Aryans in the south. They came into contact with the proto-urban population of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), also known as the Oxus Culture), which had ancient connections to northwest India, Elam and northern Mesopotamia. They assimilated, gained prominence, and transformed it, thereby attracting non-Indo-Iranian elements. In the process they had developed a new type of social structure, called the khanate, which was ruled by a landlord (khān) residing in fortified farmsteads (qala).

After 2000 BCE, most of the later Indo-Aryans moved southeast probably via Afghanistan into the Indian subcontinent (Panjab), and also southwest via the Iranian plateau into northern Mesopotamia (Mitanni kingdom), probably under pressure from the Iranians to their north. The later Iranians moved into and across the Iranian plateau, both carrying the new social structure with their languages, with a lasting impact on the socio-political structures of Iran and Afghanistan, and the subcontinent.

Linguistically, these cultural contacts with the non-Indo-European languages of the proto-urban civilization in lower Central Asia left distinct shared layers of loanwords in the lexicon of Indo-Aryan and Iranian (Lubotzky 2001).

The Iranians on their part can probably be correlated with the subsequent so-called Yaz I culture in the BMAC complex, which reflects major cultural changes towards a more rural society after 1500 BCE. They apparently remained in Central Asia, and only by the end of the second millennium BCE began to spread over the Iranian plateau.

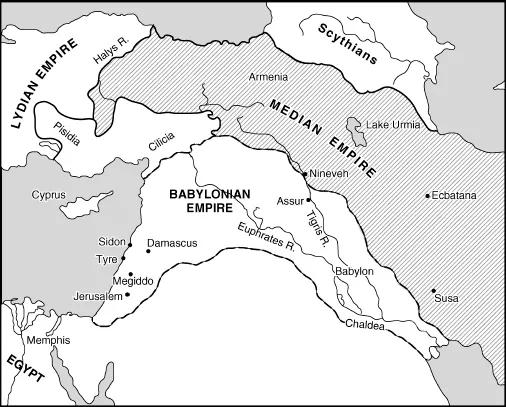

MAP 2.1 ANDRONOVO, BMAC AND YAZ CULTURES

By the second half of the eighth century BCE, Iranian Median and Persian tribes (Mada and Parswa) had already been long established among the original non-Iranian speakers of the Zagros mountain ranges of Iranian Kurdestan, according to the records of the Assyrian ruler Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 BCE). Minorsky (1957: 78) recognized that the name of the tiny village Qal’a Paswē near Solduz in Kurdestan retains the memory of the Iranian settlements (cf. also Zadok 2001; 2002). The successors of the Parswa tribes who settled in the southwest of the Iranian plateau created the Achaemenid Empire (ca. 558–330 BCE) which, beginning with the Sasanian period (224–651 CE) and thereafter, ultimately resulted in the dominance of Persian over the Iranian expanse.

MAP 2.2 MEDIAN EMPIRE (CA. 700 – CA. 558 BCE)