Chapter 1

Introduction

Occupational health and safety in the construction industry

In most industrialised and developing countries, the construction industry is one of the most significant in terms of contribution to GDP and also in terms of impact on the health and safety of the working population. The construction industry is both economically and socially important. In Australia, the value of construction work performed in residential, non-residential and engineering construction sectors in 1996–1997 was AU$40.5 billion (ABS 1997a,b). On average, the industry amounts to between 6.5 and 7 per cent of Australia’s GDP, and between 1995 and 1996, 682,000 people were employed in the construction industry in Australia (AEGIS 1999).

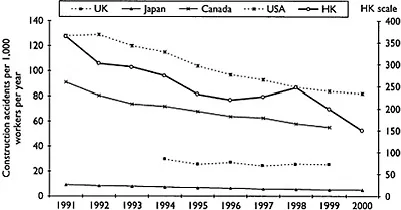

Figure 1.1 Accidents per 1,000 construction workers per year.

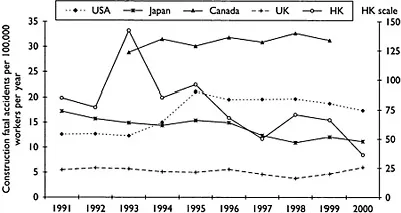

The industry provides the homes we live in, the buildings we work in and the transport infrastructure we rely upon. The construction industry contributes a great deal to improving our quality of life. However, for many workers and their families and friends, involvement in the construction industry leads to the unimaginable pain and suffering associated with an accidental death or serious injury. The construction industry continues to kill and maim more of its workers each year than almost any other industry. Typical figures for accidents and fatalities worldwide are shown in Figures 1.1 and 1.2. It should be noted that there is a huge range of incidence rates, varying from country to country. Part of this variation can be accounted for in terms of differing rates of economic and infrastructure development, but not all of it. In a project-based industry, accident rates will vary from project to project. Each project is unique, and each project type (for example, a road or a bridge or a house) has its own characteristics, methods of working, materials employed and techniques for construction. These characteristics, materials and techniques also vary from country to country. Take for example the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China and China itself. Hong Kong makes extensive use of bamboo scaffolding for building construction whereas China, the source of Hong Kong’s bamboo, does not.

The way in which construction work is organised makes the management of occupational health and safety (OHS) more challenging than in other industries (Ringen et al. 1995). The industry has diffused control mechanisms, temporary worksites and a complex mix of different trades and activities. Much work is subcontracted out and workers are employed on short-term, fixed contracts and then released at the end of a project. Such employment arrangements are associated with higher incidences of industrial accidents than where permanent employment exists (Guadalupe 2002).

Figure 1.2 Fatal accidents per 100,000 construction workers per year (Source: as Figure 1.1). (Source: Japan Statistical Yearbook, Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications; Japan International Center for Occupational Safety and Health (JICOSH); Fatal Injuries to Civilian Workers in the United States, 1980–1995; United States Bureau of Labor Statistics Data, U.S. Department of Labor; Health and Safety Statistics, HSE publication; ILO Yearbook of Labour Statistics 2001, International Labour Office, Geneva; Occupational Safety and Health Branch of the Labour Department, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.)

The fact that construction is a project-based industry is an important contextual issue. When attempting to manage a dynamic, changing environment, such as a construction site and, indeed, a construction firm, it should be borne in mind that there needs to be an appropriate organisation structure to deal with the changing nature of the project. As it moves from design to construction to in-use phases, and as problems arise (such as late delivery of materials or labour shortages) on a day-to-day basis, there is a need for rapid, decentralised decision-making, contingency planning and an appropriate, organic form of organisation. This engenders a free, independent spirit in construction site personnel and has, traditionally, led to a disregard for authority and regulations. In many instances this disregard has been taken too far and descended into unacceptable corruption and malpractice. The Housing Authority short piling case in Hong Kong (HKLEGCO 2003) and the practices revealed during the Royal Commission inquiry into the Building and Construction Industry in Australia in 2002/2003 are examples of how malpractices can drastically effect the well-being of the industry and those working in it: the cherished characteristic of independence and initiative have also given the industry a bad name.

In turn, these characteristics also make it difficult to implement programmes across the whole of the industry, and safety and health on construction sites are badly affected. Indeed, the Royal Commissioner in the Australian inquiry named OHS as the most important issue facing the building and construction industry and reported that a change in attitude was needed to reduce the number of deaths and injuries on construction sites (Feehely and Huntington 2002). Commissioner Cole argued that a new paradigm must be established by which projects are completed safely, on time and within budget, rather than just on time and within budget. The report recommended 19 changes for workplace safety and the establishment of a special industry commissioner to improve health and safety standards (Sydney Morning Herald, 28 March 2003, p. 10).

The construction industry is recognised internationally as one of the most dangerous industries in which to work. For example, McWilliams et al. (2001) report that between 1989 and 1992, 256 people were fatally injured in the Australian construction industry. The fatality rate is 10.4 per 100,000, which is similar to the fatality rate for road accidents. The construction industry’s rate of occupational injury and disease is 44.7 per 1,000 persons, which is nearly twice the all-industry rate. The Royal Commission inquiry into the Building and Construction industry reported that there are on average 50 deaths a year on Australian construction sites and that, in 1998–1999, accidents and deaths cost $109 million a year and almost 50,000 weeks of lost working time (Lindsay 2003). Similar figures are reported for the USA. Gillen et al. (2002) report that in 1998, the construction industry reported the largest number of workplace fatalities compared to any other industry. Construction accounted for 20 per cent of total work-related deaths. In 1997, the non-fatal injury rate for construction workers was 9.3 per 100 full-time workers, which is considerably higher than the all-industry figure of 6.6 per 100 full-time workers. Zwerling et al. (1996) report that in Iowa state, construction workers’ incidence of occupational injuries is 2.5 times greater than that of other occupational groups. In the UK, a similar situation exists.

Apart from the alarming number of deaths, many construction injuries lead to long-term disability. Guberan and Usel (1998) followed a cohort of 5137 men in Geneva over twenty years and report that only 57 per cent of construction workers reached 65 without suffering a permanent impairment. Falls and manual handling are prominent risk factors associated with serious injuries and long-term disability in construction (Gillen et al. 1997; Nurminen 1997). In a study of workers’ compensation data in Victoria, Australia, Larsson and Field (2002) report eleven prominent construction trades to have average injury durations longer than the all-industry average. In addition to falls and manual handling, which affected almost all construction trades, power tools, falling objects and electricity were significant risk factors in some trades. In terms of injury severity (taken as a combined index of days compensated, hospital costs and nature of injury), steelworkers, painters and rooflayers are reported to be in the most risky construction trades (McWilliams et al. 2001).

The industry’s unenviable safety statistics are often explained in terms of the construction industry’s inherently hazardous nature. The use of the term accident, which is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘an event without an apparent cause’, perpetuates the belief that occupational injuries and fatalities are chance events that cannot be prevented. This conventional wisdom is simply not true. What is of greater concern than the construction industry’s appalling OHS record is that the same types of accidents occur in construction year after year. A review of the international literature reveals that the same type of work-related deaths, injuries and illnesses occur in construction industries all over the world. Many construction hazards are well-known and, in some cases, have been studied in great depth. What is apparent is that the construction industry fails to learn from its mistakes. We understand where deaths, injuries, and, to a lesser extent, illnesses occur in the construction industry but we still fail to prevent them. The same methods of working that have been used for generations are still being used, giving rise to the same hazards and ultimately resulting in the same incidence of death, injury and illness. Furthermore, the construction industry’s organisation, structure and management methods militate against the identification and implementation of innovative solutions to the industry’s OHS problems. Improvements in OHS will not occur unless new methods of working that reduce known OHS risks are developed. However, this is likely to require that the industry’s structural and cultural barriers to the adoption of new methods of working be overcome. These structural and cultural barriers are discussed in greater detail in Chapters 3 and 10.

Some of the more common occupational health and safety hazards in construction are described below, followed by an examination of the structural and organisational factors that currently impede the improvement of OHS within the construction industry. The remaining chapters of this book suggest ways in which OHS could be better managed at project, corporate and industry levels.

Construction as a process

By way of introduction, the following paragraphs highlight some of the ‘idiosyncrasies’ of the construction industry that lead to the typical safety and health issues that the industry faces. Currently, the whole process of production in the construction industry is undergoing a radical rethink with the introduction of ‘lean and agile production’, ‘supply chain’ and ‘business process re-engineering’ paradigms. These are briefly reviewed by Rowlinson et al. (1999), who state:

It is argued that the construction industry needed to shift its focus to the underlying philosophy of lean production by recognising construction as a flow process in which construction should be seen as a hierarchical collection of value generating flows and achieve the goals of lean construction, hence the move to the term value chain rather than simply supply chain which emphasises a holistic view based around the value concept… It has been proposed that the lean revolution is essentially a conceptual revolution, at the heart of which are the flow and value models. The characteristics that the construction industry possesses are ‘one-of-a-kind’ nature of projects, site production and temporary multi-organisation. Because of this the construction industry is often seen as being different from manufacturing. Indeed, these characteristics may prevent the attainment of flows as efficient as those in manufacturing. However, the general principles of flow design and improvement apply for construction flows and in spite of these characteristics, construction flows can be improved to reduce waste and increase value in construction. As it is not possible to change the circumstances of the construction industry to fit a theory that is useful in a more stable environment such as manufacturing, other approaches are necessary. Initiatives undertaken in several countries have been trying to alleviate related problems associated with construction’s peculiarities. The one-of-a-kind feature of the construction industry is reduced through standardisation, modular coordination and widened role of contractors and suppliers. Difficulties of site production are alleviated through increased prefabrication, temporal decoupling and through specialised or multi-functional teams. Lastly the number of liaisons between organisations is reduced through encouragement of longer term strategic alliances and partnering.

All of these issues have implications for health and safety on construction sites.

Autonomous working and the subcontracting system

Wilson (1989) discusses the problems inherent in the subcontracting and labour employment practices of the industry. The problem being addressed is an international one and is, in fact, a structural problem of the economics of the construction tendering system and the organisation of small and medium-sized companies. It is obvious now that many of the problems concerning site safety on construction sites are attributable to subcontractor performance. No safety improvement scheme can be successful unless it includes subcontractors. Hence, a system must be devised to assess the performance of subcontractors, and it has been recommended that subcontractors be actually registered to work on construction projects. The Singapore List of Trade Subcontractors (SLOTS) system in Singapore provides one example of how this can be undertaken. As of 23 April 1999, all subcontractors engaged in public sector projects, with the exception of ceiling glazing and metal work trades, were required to be registered under SLOTS. SLOTS membership also determines eligibility to obtain work permits for foreign workers. The SLOTS system therefore presents an opportunity to vet the OHS management activities of sub-contractors and provides opportunities to intervene where necessary. However, despite this, incident rates have not fallen substantially in Singapore since 1999.

It is essential that the level of performance of subcontractors be appraised and the level of performance of individual contractors and subcontractors together be analysed. If it is found that certain subcontractors are regularly performing badly, then it is essential that a system be in place that allows for them to be suspended from operation. This is possible only if a clearly defined registration system for subcontractors exists. It is not possible for individual contractors to substantially improve the performance of subcontractors without some form of sanctions such as a registration system and suspension from it. A more detailed discussion of subcontracting issues follows later in this chapter.

The role of client and designer in safety

Traditionally, it has been the role of the main contractor to deal with all safety aspects of construction. However, in recent years, and with the advent of self-regulation, it has become apparent that the contractor alone cannot deal with safety issues. In fact, many safety issues arise due to design considerations. Take, for example, the decision to construct a posttensioned, pre-cast concrete bridge over a road. This requires the provision of falsework and formwork that has to be kept in place for a substantial period ...