![]()

Part 1

Evidence-based Education and the Science of Learning

1 Communication breakdown between science and practice in education

2 Different types of evidence in education

3 Is intuition the enemy of teaching and learning?

4 Pervasive misunderstandings about learning: How they arise, and What we can do

![]()

1

Communication breakdown between science and practice in education

Communication breakdown between science and practice in education

Unfortunately, educational practice does not, for the most part, rely on research findings. Instead, we tend to rely on our intuitions about how to teach and learn – with detrimental consequences.

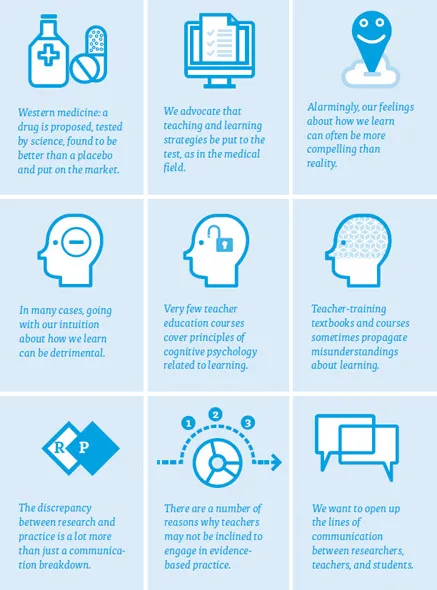

In 1928 Alexander Fleming came back from vacation and accidentally discovered a colony of mold that led to the development of penicillin, which can be used against bacterial infections (Ligon, 2004). This process then took several decades and involved clinical trials where this new drug was compared to other drugs that, at the time, were thought to help fight bacterial infections (Abraham et al., 1941). The model that we, as cognitive psychologists, are striving for in education is similar to the one exemplified by this anecdote, and used broadly in mainstream Western medicine: a drug is proposed, tested by science, found to be better than a placebo, and put on the market.

Western medicine: a drug is proposed, tested by science, found to be better than a placebo and put on the market.

Of course, any one drug does not work all the time, and so doctors will prescribe different drugs at different doses for different circumstances, conditions, and individuals.

However, Henry L. (Roddy) Roediger III reported in 2013 that, unfortunately, educational practice does not, for the most part, rely on research findings (of course, this is not always how medicine works, either; see Haynes, Devereaux, & Guyatt [2002] about how “evidence does not make decisions, people do”).

Henry Roediger

Henry L. (Roddy) Roediger III, James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Psychology, Washington University in St. Louis

Instead, somewhat dubious sources of evidence such as untested theories – or, even worse, marketing ploys by financially interested parties – drive educational fads. This concern is not new. For example, back in 1977, Fred Kerlinger (an American educational psychologist born in 1910) gave a presidential address at the American Educational Research Association conference on this issue. He argued in particular that education should pay more attention to basic research – the type of research that aims to figure out how and why people learn and behave the way they do. In this book, we review important basic processes – perception, attention, and memory – but we also focus on applied research – research that takes what we know about basic processes and applies them to real-life educational questions and settings.

How do we know whether a teaching or learning strategy is effective?

We advocate that teaching and learning strategies be put to the test, as in the medical field.

If evidence supports the effectiveness of a strategy, then we should by all means adopt it, but continue to be flexible as the science evolves. After all, would you give your child a pill that had never been scientifically tested? Or worse, one that had been scientifically tested and was shown not to work? Would you bring your child to a doctor whose practice was based on opinion and intuition alone, rather than the most up-to-date science? We know we wouldn’t. To use another example, think about the distinction between astrology and astronomy. Many of us know that one of those is science, and the other is … a fun pastime, at best.

Astronomy vs. astrology – one is science, the other is not.

However, when talking about something as broad as “learning,” there are various different scientific fields that we can draw from. In Chapter 2, we talk about different types of evidence about how we learn. For the purposes of this book, we will be focusing on evidence from cognitive psychology, because that is our area of expertise. Cognitive psychology is usually defined as the study of the mind, including processes such as perception, attention, and memory (not to be confused with neuroscience, which focuses on how the brain functions). This field of research can help us understand learning by testing hypotheses about learning strategies that are developed based on what we already know about the mind.

A different type of evidence is our own intuition. Because often, our feelings about how we learn are more compelling than reality.

Alarmingly, our feelings about how we learn can often be more compelling than reality.

For example, if students read and re-read a textbook, they will become more and more confident that they will do well on a later test. If another group of students instead take practice tests, they will be less confident in their later performance – because these tests can feel hard. But in reality, those who took the practice tests will outperform those who re-read the textbook (see Chapter 9 for more about this technique). In this case, and in many others, going with our intuition about how we learn can be detrimental.

Relying upon intuition, rather than science, can also lead us to latch on to false positives. There are certainly times when we see a positive result just because of luck or chance. But, this positive result does not mean that a particular method will work consistently over time. For an example, think about sports. If you’re an American football fan, then you can probably remember a time when the quarterback made a long-haul pass down the field that was successfully caught and run into the end zone for a touchdown. But, we know these “hail Mary’” passes certainly don’t work every time, and it would be a mistake to attempt the long-haul pass on every play. This would likely lead to an increase in losses for that team in the long run.

In many cases, going with our intuition about how we learn can be detrimental.

We will cover this scenario, and other learning scenarios where intuition can mislead us, in Chapter 3 and throughout the book.

Not only does our intuition often mislead our own selves, but often, we can end up misleading others, too. The concept of “learning styles” is one example of time, money, and energy spent on a practice that is not particularly good at increasing learning, according to the evidence (Rohrer & Pashler, 2012). You may have heard of it: “learning styles” describe the idea that students learn best in different ways. The most popular of these “styles” are visual and verbal styles: the idea is that some people are visual learners, while others are verbal learners. Importantly, proponents of learning styles claim that in order to maximize student learning, we must “match” instruction to each individual’s learning style (Flores, n.d.)

After a thorough review of the scientific literature, a group of leading researchers discovered that there was no evidence to support this view (Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, & Bjork, 2008). That is, there was not a single controlled experiment in the literature that demonstrated that matching instruction to learning styles overall helped students learn more. We talk more about this and other misunderstandings in Chapter 4. Above all, we do not want teachers and students finding themselves wasting time on strategies that are not particularly effective (see over).

Trying to implement these strategies may not be the best use of our time.

What do teachers and students learn about cognitive psychology?

We believe that researchers, teachers, and students should have an open dialogue about research related to learning. It is in everyone’s best interest to talk to one another so that we can make the best use of recommendations from learning science in the classroom, and figure out what additional research would be most helpful for teachers and students. But how do those actually involved in teaching – and those involved in training teachers – feel about using cognitive psychology findings in their teaching practices?

Laski, Reeves, Ganley, and Mitchell (2013) asked trainers of elementary mathematics teachers across the US to what extent they found cognitive psychology to be important to teaching mathematics. While most found it important, very few of the respondents actually accessed the relevant primary sources (i.e., cognitive psychology journals). When asked how often teachers read cognitive journals to inform their teacher-training practice, the most frequent response was “Never.” This response makes sense, as journal articles are dense, full of jargon, and often behind paywalls such that those outside of higher education do not typically have access.

Furthermore, according to a recent report (Pomerance, Greenberg, & Walsh, 2016), very few teacher education courses and textbooks in the US cover principles from cognitive psychology related to effective ...