![]()

1

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ENVIRONMENTAL ARCHAEOLOGY

This book is the presentation not of a hard-won theory but of an idea. My aim is to convince the reader through narrative, example and passion. Cumulation is a large part of this so that in the end you have nowhere else to go. That is why history is so attractive: it allows alternatives to be set aside while at the same time giving security in the current vogue. Archaeologists are conscious about the history of their subject, yet in practical terms, even in reality, I wonder how much of archaeological history is not of our own making, how much of it really took place at all.

Still, a historical perspective is a good way to identify and characterize environmental archaeology (Evans and O’Connor 1999) because that is how the subject developed and how it is now – an accumulation of ideas through time. Articulation with associated histories – stratigraphy (in the eighteenth century), the antiquity of humans and early archaeology (in the nineteenth century), evolution (also in the nineteenth century), ecology (in the early twentieth century) and molecular biology (in the later twentieth century) – is a part of this characterization, as is the changing role of environmental archaeologists themselves.

Earlier Years

Environmental archaeology is the study of past human environments, traditionally from archaeological excavations, sections and boreholes but increasingly from written sources, and the relationships between humans and those environments. In the early years, before the 1960s, the physical environment was seen as a backcloth to human activities. The environment was passive, with humans mapping their activities onto it, and this applied to the food plants and animals as much as to the land and weather. Equally passive were the environmental archaeologists who mapped their activities onto those of the archaeologists, although this kind of approach also applied to other aspects of archaeology – like burial practice and cities and art – which were treated in an equally narrative way. Environmental archaeology brought in the physical environment of climate and biology which conventional archaeology often ignored, but there was not really a difference between how environmental archaeologists and cultural archaeologists thought. Sometimes the environment was permissive, allowing of several options or choices, sometimes it was determining as with Braudel’s longue durée (Bintliff 1991). Environmental change led to economic change, as in the ‘oasis theory’ of the origins of agriculture in the Near East. Catastrophism was the extreme, volcanic eruptions overthrowing civilizations; and even today, when theory and ideas have moved on, we still need this kind of construction. Yet Charles Darwin was warning against it in 1859: ‘so profound is our ignorance and so high our presumption that we marvel when we hear of the extinction of an organic being; and as we do not see the cause, we invoke cataclysms to desolate the world’.

Ecological Objectivism

Immediately before the above quotation, the great man had written: ‘nature remains for long periods of time uniform, though assuredly the merest trifle would give the victory to one being over another’. Darwin understood ecology several decades before the subject came formally into being. And it is with ecology that the second major phase of environmental archaeology is recognized. Geoffrey Dimbleby, Professor of Environmental Archaeology in London’s Institute of Archaeology, firmly identified the subject with a role of hope in the utterly appalling degradation of ecosystems being wrought by human activities. His work on the heathlands of the British Isles (Dimbleby 1962) showed how wrong Thomas Hardy (1878) had been in his vision of the permanence of the Wessex heaths, ‘The untameable, Ishmaelitish thing that Egdon now was it always had been’, opening up ideas of management in relation to past change.

A phase of optimism, driven by ideas of optimization and the cost-effectiveness of energy expenditure, ensued. In transferring ecological principles to humans, archaeologists developed models which allowed for predictability in human relationships with the environment, known by the general term of ‘Middle Range Theory’. Research endeavours with major biological and geological content took place in two key areas, the origins of humans in Africa and the origins of agriculture in south-west Asia.

Three names stand out. The first is that of Louis Leakey who, in his search for the origins of humans, spawned a diversity of research, and the second is that of Lewis Binford, who was significantly responsible for the development of the Middle Range Theory in which this research was framed (Binford 1981). Big issues were at stake, especially the confrontation of our animal past as ways of explaining human aggression, male domination and war. The origins of hunting in hominids, of food-sharing and divisions of labour were key areas of research, linked closely to emergent ideologies of feminism, community and family identity, and race. The food-procuring practices in the early evolution of hominids were explored through the archaeology of their stone tools (Schick and Toth 1993). Taphonomy, a branch of research which deals with the interpretation of fossil bones, was adopted from solid-rock palaeontology and keenly diversified in early hominid and modern ethnographic studies (Behrensmeyer and Hill 1980). Investigations took place in modern African people and in modern primates on the tracks of animals from their hunting and butchery to the sharing of their meat and the fate of their bones (Rose and Marshall 1996). Feminists studied the relevance to feminism of the perceptions and creations of these researches (Haraway 1989). And ‘sociobiology’ synthesized the humanities within biology in a savage debate, of which two of the more sober contributors were E. O. Wilson (1975) and Marshall Sahlins (1977).

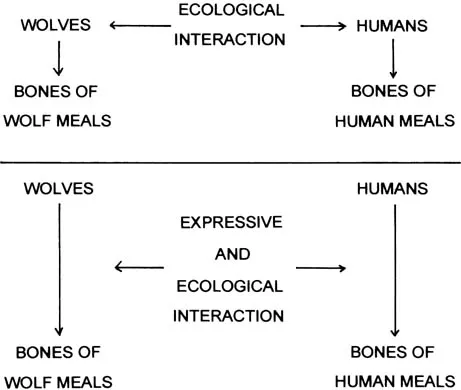

The importance of these issues ensured well-funded research, and the benefits for environmental archaeology in both theoretical and practical aspects were enormous. Much of the work on bones has been about the separation of human (or hominid) and animal carnivore assemblages, and there has been specific interest in the origins of hunting in hominids. A problem with using modern comparisons between bone assemblages of animal carnivore and human origin as templates for archaeology, however, is that neither animal behaviour nor human behaviour takes place in isolated worlds of nature or culture, animal or human. This is irrespective of anthropological constructs as to the existence of such a division or not (Ingold 1996b; Dickens 1996: 6). Rather it refers to the fact that the behaviour of animal carnivore and hominid is each influenced by the other and so, therefore, are the bone assemblages which each leaves behind (Figure 1.1, upper). To be sure, there are distinctive animal and human contributions to their own activities, and some of these, such as the presence of toothmarks and cutmarks respectively and the removal of particular components of carcasses away from death sites, can be identified; but other traces, such as the intensity of gnawing or cutting as related to the influence of other species at the death site, could not. Interaction is partly ecological, animals and hominids adjusting their behaviour in relation to competition or cooperation with other species, but it is also expressive (Figure 1.1, lower), about social influence and power. We will return to this shortly.

Figure 1.1 Different theories of relationships between animals and humans. In the upper part of the diagram is the conventional ecological theory; in the lower part, living creatures of two species and the bones of their meals relate to each other through social expression.

(Compare Figure 9.1.)

The third in my trilogy of memorable names from this phase of environmental archaeology is that of Eric Higgs who, with his search for the origins of agriculture in south-west Asia, was responsible for the development of ‘Site Catchment Analysis’, or SCA (Higgs and Vita-Finzi 1972). This is encompassed within the methodology of Middle Range Theory in that it uses a practical logic of how land might be exploited. It suggests how the environment was exploited from a particular site with reference to the potential of the land. Land-use was seen as being mapped onto the environment, with decreasing intensity of use as one moved away from the site, with the exception of local hotspots of exploitation as for quarrying stone or dealing with specialized resources like hay which were not encompassed within the catchment.

Aside from issues like changing land type, uncertainties about technology and cultural choice, a problem was the question of maximization of effort in procuring food and other resources like fuel and shelter. It is questionable that people use the land to its full potential in a cost-effective way, reducing their intensification as they move outward from the settlement or site. There is always some slack. This means that there need not be a watertight equation of land potential and its exploitation. Moreover, exploitation from a single site is unrealistic, even today in subsistence farms which one might think of as the epitome of settlement stability and tradition. People move around quite a lot. As we know from modern studies of agro-pastoralists in semi-arid areas (among others), there is considerable temporo-spatial agility in the way land and settlements are used, with people moving – often at irregular intervals (not the regular seasonal ones we think of in our comfortable ideas of transhumance or hunter-gatherer mobility) and through a variety of settlement sites, variously owned – in various age and gender groupings. Settlements can stay deserted and in uncertain ownership, only to be reclaimed and reoccupied uncontentiously after several years.

As a result of such problems, more recent studies have looked at not just one site but several sites of resource exploitation and activity in a regional – or strategic – system. Sites were seen as being related to each other, with the added input of tactical influence in catchments (Bailey and Davidson 1983). One site could be a look-out site for game, another a regional centre where people came to exchange ideas, a third an isolated settlement. Fieldwalking, in which land-use was investigated by surface survey, encouraged the regional approach and especially the search for new sites and an investigation of what was going on in the areas between sites (Ch. 6). This was an important advance and was part of a general shift within archaeology towards regional studies. Recognition of discrepancies between theoretical catchments – as defined by SCA and the use of Thiessen polygons – and actual ones as discovered by fieldwalking, excavation or from literary sources, allowed exploration of socio-political factors, rather than just the raw economic ones, to which catchments might relate (Ch. 6, p. 144 and Figure 6.12) (Bintliff 1988). Such investigations allowed power and sociality to be added to the equation, and were an important advance in our understanding. So the trend towards a regional approach was more than just a view of bigger areas and a more complete economic picture, it was a trend towards the incorporation of socio-political factors as well.

This brings us to a question which has been addressed more by human geographers and anthropologists than by environmental archaeologists, and that is the relative influences of the physical environment and socio-cultural factors in human practice. The two perspectives were used in conjunction by Fernand Braudel (1949) in his study of Early Modern Mediterranean history but each in the context of different time dimensions (Bintliff 1991; Gosden 1994). The history of short-term events and medium-term structures such as demographic cycles was seen as occurring in a framework of social and economic directives, whereas that of the long-term, the longue durée, was environmentally driven. Several people have drawn attention to the problem of completely understanding a history which is framed in two different infrastructures. One of my purposes in this book is to show how these two alternatives, in being driven, unilineal, schemes, are in effect the same side of a coin, the other side of which is the use of environments in social expression. Seeing the creation of socialities as taking place through the physical environment, and at scales which range from the interests of single individuals to much larger groups, allows all three of Braudel’s time levels to be understood in the one scheme (Ch. 2, p. 35; ).

The Damage of a Culture of Maximization

Conventional ecology sees maximization in the use of materials and energy as critical in our understanding of the way in which plants and animals behave. These ideas seem to have been taken from the precepts of evolutionary theory, especially those of struggle and fitness in which survival of the individual and perpetuation of the species are key goals. Yet of the triple piers of modern biology, it was ecology that came first into the world, even if it was a lifeless ecology, and it is interesting to speculate how things might have gone had ecology been developed as a discipline before the discovery of evolution.

It is fruitful, too, to think about the development of evolutionary theory in a socio-cultural environment different from that of the Industrial Revolution and empires. Is it necessarily true, for example, that animal and plant communities struggle, that they behave in the energy-effective way that Darwin envisaged, enshrined in his unfortunately worded phrases ‘the struggle for existence’ (actually taken from Thomas Malthus) and ‘the survival of the fittest’? Darwin lived in an age of Protestant work ethic, in the country where the Industrial Revolution began, and in an empire which needed concepts and schemes like evolution to legitimate its increasing conquest of unfamiliar races of humanity. Malthus too, only a bit earlier. But Malthus based his ideas on marginal communities where there was pressure, like mountain regions. One of his case studies was in Tibet. Another was the environment of emergent industrial towns and cities with their unusual pressures and exceptionally high rates of population. Darwin visited the Galapagos Islands, but these are islands where one can expect strong selection pressures, and quite distant from the continental mainland from which genetic dilution might come. They had also been settled by people several hundreds of years before Darwin, so the animals and plants there had been subjected to human selection pressures too. And to put things into further perspective, it was Linnaeus’s species themselves, with their little expressions of difference in their DNA, that created evolution in the first place, not the other way round.

This is not a chapter about evolution, but our understanding of how evolution takes place has a strong part to play in our views about ecology. Logically it ought to be the other way round, as I have just explained, but as socially constructed it is not. Yet if we could see evolution as driven by social expression of individuals and groups of plants and animals, as being more directed than we think, we could get away from ideas of struggle, competition and fitness and open up new possibilities for relationships in ecology. Animals and plants could be seen as behaving in an individualistic, sentient and expressive way, with an active sociality in their lives as important as growth, maintenance and reproduction. For example, the distinctions between Darwin’s finches of the different Galapagos Islands are mainly in the beaks, a feature that is usually seen as having evolved through different feeding habits. Yet it is mainly through these differences in the beaks that these birds communicate, so we could see evolutionary separation as having come about through socialities primarily and by feeding as a consequence of that.

Indeed, work in several animal groups is showing that much behaviour is about establishing, maintaining, and even opposing social relationships. Many animals symbolize or express relations through their behaviour or through the use of artefacts or land. Indeed, such behaviour is probably widespread in the animal kingdom and perhaps even among plants.

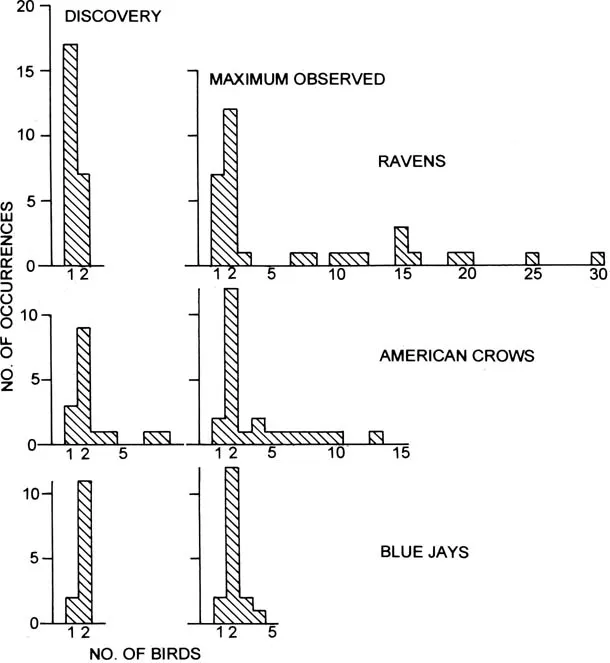

Ravens in Maine and Vermont advertise the presence of food to other ravens, calling out with specific kinds of cries when they discover food. Discoveries are made by one raven or at most a pair, yet there is deliberate, active, recruitment of others to the food (Figure 1.2) (recruitment is also directly from the roost at distances too far away for vocal recruitment alone, so other, as yet unknown, factors are involved). Mostly it is young individuals, still unmated, that behave in this way, not the mated, established, pairs. This type of behaviour is counter to what one would expect if there were struggle for survival; drawing attention to food would seem to be sacrificing reproductive success. It is suggested that feeding allows the development of socialities, ranking especially among the young males, for the purpose of selecting mates. This, of course, can only be done in company, so discovery of food needs to be advertised and other ravens recruited for it to serve its purpose (Heinrich 1991).

Figure 1.2 Differences between the number of birds discovering baits and subsequently utilizing them in three species of corvid (crow family) in Maine. In the raven, Corvus corax, two-thirds of the baits are discovered by single birds and the other third by pairs; subsequently large numbers use the bait. In the other two species, most discoveries are made by pairs and there is not so much subsequent recruitment. These data suggest active recruitment in ravens to the bait, behaviour which benefits social relationships in the community.

(Based on Heinrich 1991: fig. 2.)

Work on primates in the last two decades has shown that they spend a lot of time socializing and establishing relations but that these are disbanded often within hours and serve little useful purpose in terms of survival and the passing on of genes. Shirley Strum (1987), working on baboons, showed that aggression and dominance were neither inevitable nor central, and not the only influences in baboon social lives. Much more relevant than permanent dominance hierarchies ...