Historic Preservation Comes of Age

In recent years interest in historic preservation has been kindled. In 1965, fewer than 100 communities had taken steps to protect neighborhoods of historical or architectural importance; by 198Q, almost 1,000 localities had designated one or more historic districts.1 In 1970, there were approximately 2,000 entries on the National (federal) Register of Historic Places; a decade later there were almost 20,000.2 Interest in preserving the past is reflected in other ways. Membership in the National Trust for Historic Preservation has grown dramatically. Graduate-level historic preservation programs have been established at Columbia and many other universities. Preservation literature has proliferated; conferences on the subject have become commonplace.3

The current advocacy for and support of historic preservation is due to numerous, interrelated factors. Urban-renewal excesses in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly widespread demolition, evoked a turning to preserving and building on the past. Dissatisfaction with the uniformity of suburban tract construction in the postwar period has instilled a growing appreciation of the distinctiveness and value of the historic built environment. Preparation for the nation’s bicentennial in 1976 sparked further interest in preserving the past—both cultural and physical. And the rapid rise of construction costs in the late 1970s gave new value and attractiveness to the extant residential and nonresidential stock as a lower cost alternative to new development.

Historic preservation is also viewed as not only an end in itself but also as an important means for revitalizing declining urban areas. The theme of preservation has served as an important rallying point for numerous urban restoration activities.4 Many of the leading examples of residential urban turnabout—Brooklyn Heights and Park Slope in New York City, Society Hill in Philadelphia, and Beacon Hill in San Francisco—have historical motifs. The same is true of numerous nonresidential rehabilitation success stories—Boston’s Faneuil Hall, San Francisco’s Ghiradelli Square, and Denver’s Larimer Square.5

Federal, State, and Local Historic Preservation Mechanisms/Programs

Interest in historic preservation has evoked a series of federal, state, and local protective mechanisms and programs.

Federal Historic Preservation

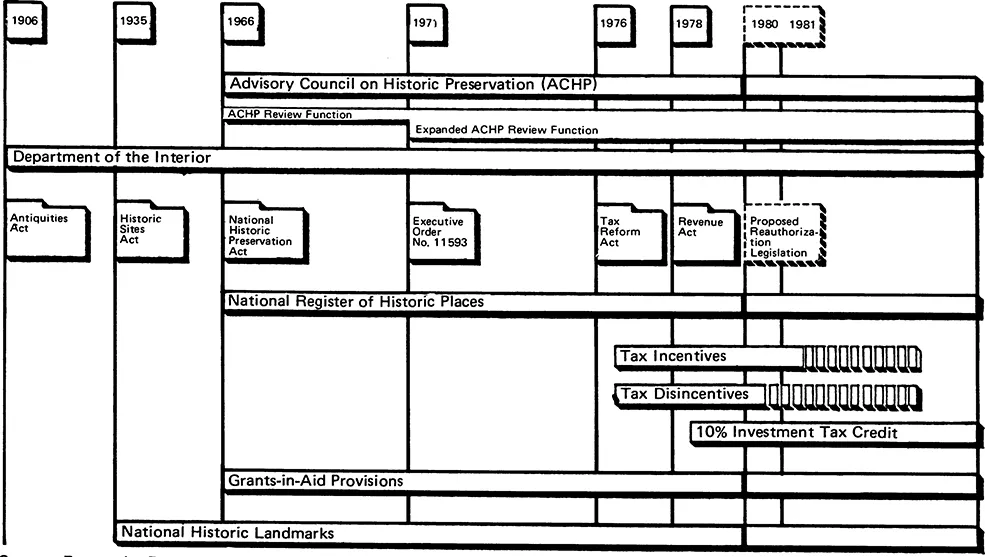

Mechanisms/Programs (See Exhibit 1)

Federal historic preservation activity dates from the period following the Civil War when the federal government acted to preserve battlefields. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Antiquities Act of 1906 gave the President the power to declare and set aside national monuments.6 In 1935, the National Historic Sites Act empowered the Secretary of the Interior to acquire and preserve properties of national historical significance.7 In 1949, Congress chartered the National Trust for Historic Preservation as a nonprofit corporation to facilitate public interest and participation in preservation.8

While the federal government’s involvement in historic preservation goes back many years, its most important activities are quite recent. The National Historie Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA)9 set the tone and mechanisms of the current federal intervention. NHPA declared that “the historical and cultural foundation of the nation should be preserved”10; it established four major elements to achieve this goal11: (1) the National Register of Historic Places would inventory the nation’s cultural resources; (2) National Historic Preservation Fund would provide grants-in-aid to states carrying out the purposes of NHPA (i.e., surveying historic properties, making nominations to the National Register, and providing financial assistance for historic property acquisition/restoration) ; (3) a new cabinet-level body, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), would advise and coordinate federal preservation efforts; (4) a review process (section 106), spearheaded by ACHP, would evaluate federal actions affecting National Register properties. This impact evaluation procedure was designed to protect National Register entries from adverse federal activity. (In 1976, section 106 review was extended to properties eligible for the National Register.)

A decade after the NHPA, the federal government provided a series of important tax incentives for income-producing historically certified properties. The Tax Reform Act of 197612 provided both “carrot and stick” measures. To encourage rehabilitation of historic buildings, section 2124 of the 1976 act allowed a rapid (60-month) depreciation of renovation expenditures.13 To discourage demolition of landmarks, section 2124 disallowed for tax purposes (1) deduction of the expenditures incurred in demolishing an historic property14 and (2) rapid depreciation of the new building replacing the historic structure.15

The 1981 changes by the Reagan administration and Congress have modified some of the above-mentioned federal preservation mechanisms/ programs. There have been changes in the National Register nomination/ listing procedure. To illustrate, for the first time, a property cannot be listed on the National Register over the objections of its owner. Certain preservation tax measures have been revised. For example, the section 2124 five-year rehabilitation write-off was repealed as were some of the penalties for demolishing historic buildings (i.e., disallowing rapid depreciation on the replacement structure). At the same time, new and quite generous tax measures for historic buildings have been introduced. Rehabilitation expenditures on such properties qualify for relatively preferred depreciation treatment (concerning such matters as the depreciation schedule, recapture rules, and adjustment to basis), albeit less generous than the repealed five-year write-off. In addition, one-quarter of the expenditures incurred in renovating the historic building can be applied for an income tax credit.16 The latter is one of the most generous investment provisions provided by the 1981 Economic Recovery Act.

State Historie Preservation Mechanisms/Programs

By enacting enabling legislation, state governments have authorized local preservation activity—the cutting edge of the preservation effort, as we shall see momentarily. For the most part, however, states serve as the operating-arm partners of the federal preservation thrust.17 With federal assistance, states survey historical properties, nominate eligible buildings to the National Register, and grant aid for the acquisition and/or rehabilitation of historic resources.18 States also participate in the section 106 review process; their efforts in this regard are expected to assume greater importance under the Reagan administration’s shift of regulatory responsibility from the federal to state governments.

Local Historic Preservation Mechanisms/Programs

The most important historic preservation controls are those imposed by local communities. Many localities have enacted procedures whereby architecturally and/or historically significant properties can be designated as landmarks. Typically this process works as follows: A local commission identifies buildings that meet specific criteria of architectural, historical, or cultural significance and are worthy of preservation. These recommendations are submitted to the city council and, after a public hearing, the council decides whether historic status should be accorded. Designation protects the landmark by delaying or prohibiting inappropriate alterations to the property’s facade, unsuitable interior changes (in the case of an interior landmark), and demolition of the structure itself. Property changes are allowed only if they conform to the prevailing architectural style, historical motif, and so on19.

Local preservation regulation requires the owner of the designated property to obtain approval of the historic preservation commission for any alteration he proposes for his property. The variations in the basic theme are myriad. The ordinance may apply to individually designated landmarks or, as is more often the case, to all properties within a designated historic district. Control may extend to demolition and new construction or be limited to exterior alterations. Failure to obtain permission may prohibit the owner from carrying out his proposal or simply require him to wait.

No comparable controls are found at othe...