- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Writing for Assessment

About this book

This text helps students to develop the writing skills they need to succeed in AS and A2 level English; offers a step-by-step guide to approaching writing tasks and structuring a response; looks at a range of writing tasks, from argumentative essays to data-based investigations; provides Personal Audit Sheets (PASS) to help students assess their own writing skills and make practical steps to develop them; can be used as preparation for both coursework and exams.

Written by an experienced teacher, author and AS and A2 level examiner, Writing for Assessment is an essential resource for all students of AS and A2 level English Language, English Literature, and English Language and Literature

Information

CHAPTER 1 AUDITING YOUR WRITING SKILLS

The aim of this chapter is to get you thinking about the way your own writing skills have developed, and about the particular types of writing required of you on your English course. In an ideal world, these two factors – your own writing abilities, and what your course requires – would be perfectly matched. However, in the real world it may be a different story: your course may prioritise certain types of writing you are less familiar with, and downplay some aspects that you know well.

By the end of the chapter, you will be in a position to know which types of writing are a strong part of your repertoire, and which types you will need to practise further. Make notes as you go through each exercise, in preparation for your Personal Audit Sheets (PASS) at the end of the chapter.

Exercise 1 – Your Writing Repertoire

Every individual has a range of writing styles, or repertoire, to select from according to the needs of a particular context.

Make a list of all the types of writing you have done in the last week. For each type of writing you identify, specify who the audience was and also say what the (main) purposes were. When you have finished, write some notes about how easy or difficult you found each type of writing.

There are no answers to this exercise, but what you do here will form the basis of further work to follow.

Table 1.1 is a brief example to get you started. It is from a young lecturer in his first year of teaching:

Table 1.1 List of writing types

Notes on difficulty

The lecture notes were the most difficult to write because I’m new to this activity and I found myself having to do several things at once. For example, I had to look up quite a few references. I had to get my ideas into a logical order. I was writing with a view to how the lecture would sound when delivered, which meant that I had to think about such things as how long it would last. So the writing was really writing-to-be-spoken.

The memo was a little tricky because although it didn’t involve much text, I had to get the wording absolutely right because the writing was going to act as a permanent record.

The email was the fastest piece of writing that I did and enjoyable because I included lots of stories about what’s been going on. It did involve quite a lot of shaping of the text because I wanted to get maximum effect for some of the things I was describing, but I wasn’t too bothered about correctness. I found the writing a relaxing experience which put me in a good mood because I could imagine my brother laughing as he read it.

The previous exercise will have shown you some of the factors at work in your own repertoire, for example:

- That you already have an extensive knowledge of different types of writing

- That you practise some types of writing more often than others

- That some types of writing pose more of a challenge than others

- That difficulty is sometimes simply the result of unfamiliarity

- That difficulty can arise from the need to use a particular type of language

- That difficulty can arise because one piece of writing may have to address more than one audience or purpose

You were probably also aware as you worked on the previous exercise that you could divide your writing into types that were to do with your social life and leisure activities – for example, text messaging friends in order to meet up – and types that were more associated with academic work, such as notes and essays.

Types of academic writing such as essays and reports are sometimes described as if they were acquired late in life, added on to an individual’s writing repertoire after all the other types of writing, such as stories, diaries and poems, have been learnt. Actually, this is not true at all. Young children, if given the opportunity, will go way beyond just producing story forms. They are perfectly capable of constructing reports and accounts of the world around them that are quite analytical. This is because the thinking that lies behind some of the writing we call academic is actually a basic, everyday kind of thinking.

Exercise 2 – Early Repertoires

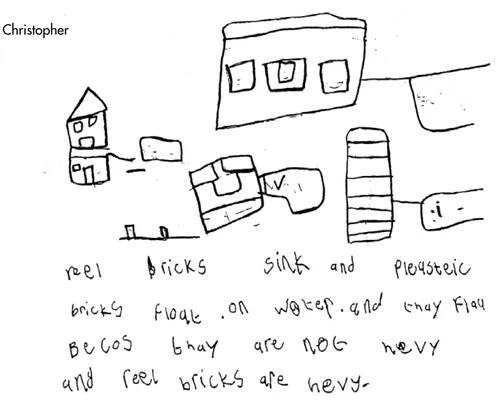

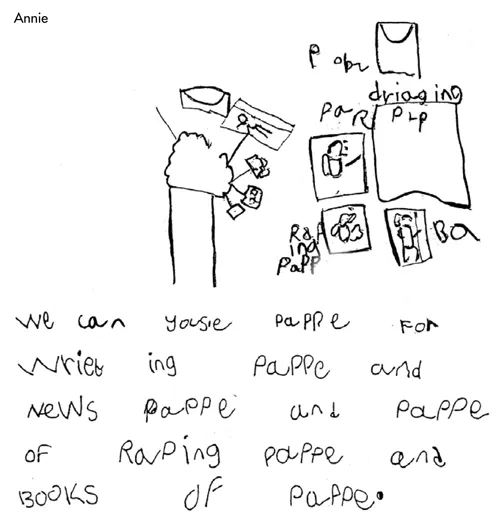

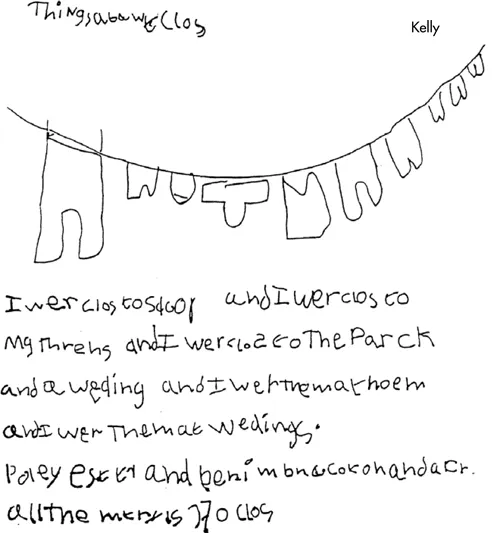

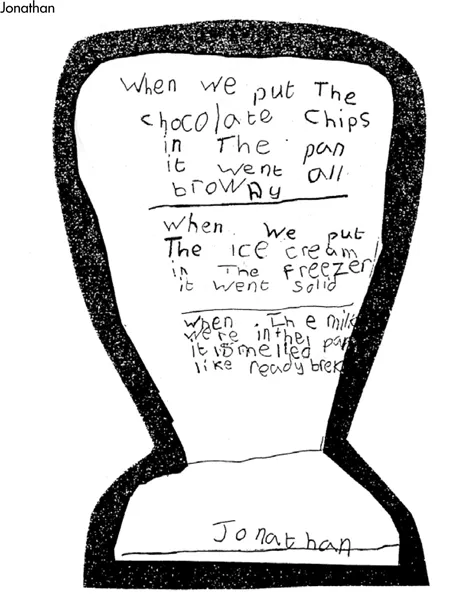

Read through the children’s writing in the four texts below.

In what ways are these young children (all aged 5–6) being academic?

When you have finished the exercise, check the suggestions for answer on these texts at the back of the book.

The children had been working on a theme based on ‘materials’. Much of this had been in the form of scientific investigations in order to find out about different types and uses of materials both natural and man-made. Towards the end of the half-term the teacher had asked the children to choose one aspect of the topic they particularly enjoyed in order to report back their findings to children in the adjacent Year 1 class.

Figure 1.1 Children’s writing

The children made ice cream and observed changes of state as it was made and frozen. When reporting they each had to think of three changes that they had observed.

The children’s writing you have been studying arose because teachers were encouraging their pupils to attempt genres other than narratives (stories). The fact is, your own writing profile – your skills, the gaps in your knowledge – is the result of those writing experiences you have had, both within formal education and beyond. If you feel ignorant of some ways of writing, it could be because you never had a reason to practise particular styles with any regularity.

Exercise 3 – Language Across the Curriculum

Think in some detail about your own writing development, focusing particularly on the types of writing you did earlier in the school curriculum or on previous courses. Make some notes as you go along on each of the questions below.

Think first about the writing you did in English classes:

- What different types of writing have you previously done for English work?

- Of the different types of writing you did, which did you like most/least, and why?

- Can you identify types of writing that you did well, and types where you struggled?

- What were the most frequently expressed comments by markers about your writing in English?

Of course, it isn’t only in English classes that students do written assignments. Now think about the types of writing you did for other classes:

- Give some examples, from other subject areas, of types of writing you did that were different from those you did in English

- Were you aware of learning different forms of language use in those other subject areas?

- Were you successful or unsuccessful at particular types of writing in other subject areas?

- Ask your teaching staff whether your school/college has any policies on literacy and language use across the curriculum (for example, policies for particular Key Stages or Key Skills). If so, identify what the school/college aims are for your literacy development

Exercise 4 – Literacy for Assessment

Get hold of a copy of the course description or exam board specification for the course you are on, and make a list of the different types of writing you are going to be assessed on. Below are some common assessment vehicles, but you may well find others. Tick those that apply to you, noting details for yourself of where the assessment occurs (e.g. end of unit exam, coursework, a particular unit or module, etc.). Then add any further examples you find. When you have finished the list, write a definition for each example of writing that you will have to produce, explaining what makes each written genre distinctive from the others:

- Logs

- Diaries

- Reports

- Commentaries

- Short answers – e.g. text analysis

- Research projects/investigations

- Essays

Some suggested definitions are given at the back of the book.

ACADEMIC LITERACY

It is impossible to talk about academic writing without also talking about academic reading. In order to understand how texts work, people need to become acquainted with a variety of written texts. Reading and understanding the material produced by a particular group are also a way for new members to become integrated. Think, for example, of any of your interests or pastimes, and the extent to which you have become familiar with the writing produced on that theme: if you like cookery you might read cookbooks and food columns; if you like football you might read fanzines and match write-ups; if you like shopping you might read magazines and catalogues. It is then likely that, if asked, you would be able to produce a piece of writing that was convincingly close to one of these genres, because you will have read them so often.

The same idea is true of the academic community. Those people who succeed in producing academic writing will have encountered many examples on which to base their own language choices – options both to follow and, equally important, to reject. This involves active reading, thinking and note making. And, although this section is termed ‘academic literacy’, which technically refers to reading and writing, you will see that written language is also supported by the oral work you do.

There are many types of academic material that can play an important role in supporting your own academic writing. Here are some:

- Teachers’ oral presentations

- Teachers’ written notes

- Class discussions

- Newspaper articles

- Textbooks

- Journal articles

All the genres above can contribute to your development of a good academic style. The oral genres – you...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- ROUTLEDGE A LEVEL ENGLISH GUIDES

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- TABLES

- PREFACE

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- CHAPTER 1: AUDITING YOUR WRITING SKILLS

- CHAPTER 2: UNDERSTANDING ESSAY QUESTIONS: TRIGGER WORDS

- CHAPTER 3: UNDERSTANDING ESSAY QUESTIONS: SECTIONS AND DIVISIONS

- CHAPTER 4: INVESTIGATING

- CHAPTER 5: ARGUING

- SUGGESTIONS FOR ANSWER

- REFERENCES

- GLOSSARY

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Writing for Assessment by Angela Goddard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.