- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As the public face of American has changed, so has the face of its foreign policy. Diversity and U.S. ForeignPolicy, goes beyond the traditional texts that focus on foreign policy only as a contest between super-powers to grapple with multiculturalism in America and multipolarism on the international state.

Information

Part 1

Section 1

Growing Demographic Diversity in U.S. Society

The major issue in Section One is the emergence of new patterns of domestic demography, political mobilization, and economic clout among minority groups in the United States as immigration from Third World countries has soared. A central element of globalization is the accelerated movement of people, goods, services, and money across national borders. One consequence is that most industrial nations are now much more demographically diverse than they were only a generation ago. The United States is a particularly prominent example of growing diversity, and the authors in this section analyze the country’s changing demographic dynamics. In the United States, the 1980s and 1990s saw the greatest rates of inward migration since 18901915. The addition of millions of new Americans in such a compressed period of time has altered the demographic and racial face of American society. Immigration has created new employment opportunities and new political dynamics, each with its own strengths and stresses. This huge horizontal movement has been accompanied by some upward mobility as well, as people of color enter for the first time the senior ranks of business, government, and the professional world, though still in very modest numbers. The raw demographics that Johnston describes find their more literary expression in essayist Robert Kaplan’s unique view of the new American melting pot that many cities on the West Coast have become, from Vancouver to Seattle to Los Angeles. In Kaplan’s view, some of these cities are becoming “Asianized cit(ies) of the Pacific Rim.” According to one of Kaplan’s respondents, the cultural mix of Asians and WASPs is “the most potent in the history of capitalism.

1 Global Workforce 2000

The New World Labor Market

WILLIAM B. JOHNSTON

March-April 1991

For more than a century, companies have moved manufacturing operations to take advantage of cheap labor. Now human capital, once considered to be the most stationary factor in production, increasingly flows across national borders as easily as cars, computer chips, and corporate bonds. Just as managers speak of world markets for products, technology, and capital, they must now think in terms of a world market for labor. The movement of people from one country to another is, of course, not new. In previous centuries, Irish stonemasons helped build U.S. canals, and Chinese laborers constructed North America’s transcontinental railroads. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was common to find Indian engineers writing software in Silicon Valley, Turks cleaning hotel rooms in Berlin, and Algerians assembling cars in France. During the 1990s, the world’s workforce will become even more mobile, and employers will increasingly reach across borders to find the skills they need. These movements of workers will be driven by the growing gap between the world’s supplies of labor and the demands for it. While much of the world’s skilled and unskilled human resources are being produced in the developing world, most of the well-paid jobs are being generated in the cities of the industrialized world. This mismatch has several important implications for the 1990s.

- It will trigger massive relocations of people, including immigrants, temporary workers, retirees, and visitors. The greatest relocations will involve young, well-educated workers flocking to the cities of the developed world.

- It will lead some industrialized nations to reconsider their protectionist immigration policies, as they come to rely on and compete for foreign-born workers.

- It may boost the fortunes of nations with “surplus” human capital. Specifically, it could help well-educated but economically underdeveloped countries such as the Philippines, Egypt, Cuba, Poland, and Hungary.

- It will compel labor-short, immigrant-poor nations like Japan to improve labor productivity dramatically to avoid slower economic growth.

- It will lead to a gradual standardization of labor practices among industrialized countries. By the end of the century, European standards of vacation time (five weeks) will be common in the United States. The forty-hour work week will have been accepted in Japan. And world standards governing workplace safety and employee rights will emerge.

Several factors will cause the flows of workers across international borders to accelerate in the coming decade. First, jet airplanes have yet to make their greatest impact. Between 1960 and 1988, the real cost of international travel dropped nearly 60 percent; during the same period, the number of foreigners entering the United States on business rose by 2,800 percent. Just as the automobile triggered suburbanization, which took decades to play out, so will jumbo jets shape the labor market over many years. Second, the barriers that governments place on immigration and emigration are breaking down. By the end of the 1980s, the nations of Eastern Europe had abandoned the restrictions on the rights of their citizens to leave. At the same time, most Western European nations were negotiating the abolition of all limits on people’s movements within the boundaries of the European Community, and the United States, Canada, and even Japan began to liberalize their immigration policies. Third, these disappearing barriers come at a time when employers in the aging, slow-growing, industrialized nations are hungry for talent, while the developing world is educating more workers than it can productively employ.

These factors make it almost inevitable that more workers will cross national borders during the 1990s. Exactly where workers move to and from will greatly influence the fates of countries and companies. And even though those movements of people are not entirely predictable, the patterns already being established send strong signals about what is to come.

THE CHANGING WORLD LABOR FORCE

The developments of the next decade are rooted in today’s demographics, particularly those having to do with the size and character of various countries’ work forces. In some areas of the world, for instance, women have not yet been absorbed in large numbers and represent a huge untapped resource; elsewhere the absorption process is nearly complete. Such national differences are a good starting point for understanding what the globalization of labor will look like and how it will affect individual nations and companies.

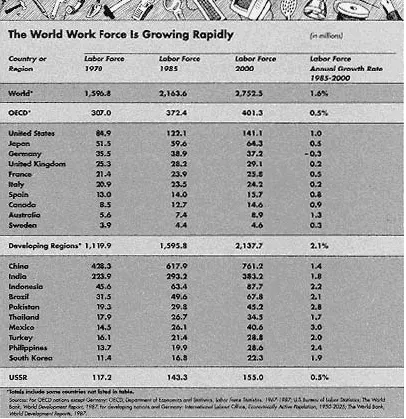

Although looming labor shortages have dominated discussion in many industrialized nations, the world workforce is growing fast. From 1985 to 2000, the work force is expected to grow by some six hundred million people, or 27 percent (that compares with 36 percent growth between 1970 and 1985). The growth will take place unevenly. The vast majority of the new workers—570 million of the 600 million workers—will join the workforces of the developing countries. In countries like Pakistan and Mexico, for example, the workforce will grow at about 3 percent a year. In contrast, growth rates in the United States, Canada, and Spain will be closer to 1 percent a year, Japan’s workforce will grow just 0.5 percent, and Germany’s workforce (including the Eastern sector) will actually decline. (See Exhibit 1.)

The much greater growth in the developing world stems primarily from historically higher birthrates. But in many nations, the effects of higher fertility are magnified by the entrance of women into the workforce. Not only will more young people who were born in the 1970s enter the workforce in the 1990s but also millions of women in industrializing nations are beginning to leave home for paid jobs. Moreover, the workforce in the developing world is also better and better educated. The developing countries are producing a growing share of the world’s high school and college graduates.

When these demographic differences are combined with different rates of economic growth, they are likely to lead to major redefinitions of labor markets. Nations that have slow-growing workforces but rapid growth in service sector jobs (namely Japan, Germany, and the United States) will become magnets for immigrants, even if their public policies seek to discourage them. Nations whose educational systems produce prospective workers faster than their economies can absorb them (Argentina, Poland, or the Philippines) will export people.

Beyond these differences in growth rates, the workforces of various nations differ enormously in makeup and capabilities. It is precisely differences like these in age, gender, and education that give us the best clues about what to expect in the 1990s.

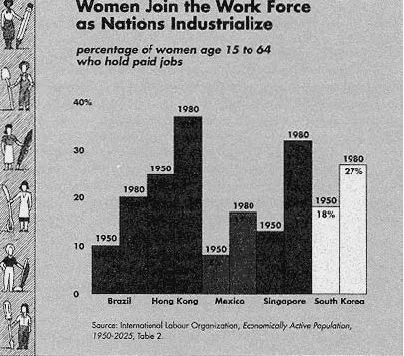

Women will enter the workforce in great numbers, especially in the developing countries, where relatively few women have been absorbed to date. The trend toward women leaving home-based employment and entering the paid workforce is an often overlooked demographic reality of industrialization. As cooking and cleaning technologies ease the burden at home, agricultural jobs disappear, and other jobs (especially in services) proliferate, women tend to be employed in the economy. Their output is suddenly counted in government statistics, causing GNP to rise. (See Exhibit 2.)

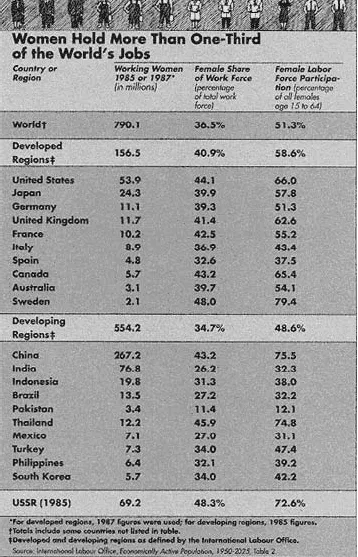

More than half of all women between the ages of fifteen and sixty-four now work outside the home, and women comprise one-third of the world’s workforce. But the shift from home-based employment has occurred unevenly around the world. The developed

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2 nations have absorbed many more women into the labor force than the developing regions:

59 percent for the former, 49 percent for the latter. (See Exhibit 3.)

59 percent for the former, 49 percent for the latter. (See Exhibit 3.)

More telling than the distinction between the developed and developing worlds, though, are the differences in female labor force participation by country. Largely because of religious customs and social expectations, some developed countries have relatively few women in the workforce, and a small number of developing nations have high rates of female participation. The fact that women are entering the workforce is old news in Sweden, for instance, where four-fifths of working-age women hold jobs, or in the United States, where two-thirds are employed. Even in Japan, which is sometimes characterized as a nation in which most women stay home to help educate their children, about 58 percent of women hold paid jobs. Yet highly industrialized countries such as Spain, Italy, and Germany have fairly low rates of female participation. And for ideological reasons, China, with one of the lowest GNPs per capita of any nation, has female participation rates that are among the world’s highest.

The degree of female labor force participation has tremendous implications for the economy. Although a large expansion of the workforce cannot guarantee economic growth (Ethiopia and Bangladesh both expanded their workforces rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s but barely increased their GNP per capita), in many cases, rapid workforce growth stimulates and reinforces economic growth. If other conditions are favorable, countries with many women ready to join the workforce can look forward to rapid economic expansion.

Among the developed nations, Spain, Italy, and Germany could show great gains. If their economies become constrained by scarce labor, economic pressures may well overpower social forces that have so far kept women from working. In developing countries

Exhibit 3 where religious customs and social expectations are subject to change, there is the potential for rapid expansion of the workforce with parallel surges in the economy.

Women are unlikely to have much effect in many other countries—Sweden, the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Japan, all of which have few women left to add to their workforces. They may be able to redeploy women to more productive jobs, but the economic gains will likely be modest. Also, countries that maintain their current low utilization of women will have a hard time progressing rapidly. It is hard to imagine Pakistan, for example, a largely Moslem country where 11 percent of women work, joining the ranks of the industrialized nations without absorbing more of its women into the paid workforce.

As more women enter the workforce worldwide, their presence will change working conditions and industrial patterns in predictable ways. The demand for services such as fast food, day care, home cleaners, and nursing homes will boom, following the nowfamiliar pattern in the United States and parts of Europe. Child rearing and care for the disabled will be increasingly institutionalized. And because women who work tend to have more demands on them at home than men do, they are likely to demand more time away from their jobs. It is plausible, for example, that some industrialized nations will adopt a work week of 35 hours or less by the end of the 1990s in response to these time pressures.

The average age of the world’s workforce will rise, especially in the developed countries. As a result of slower birthrates and longer lifespans, the world population and labor force are aging. The average age of the world’s workers will climb by more than a year, to about thirty-five, during the 1990s.

But here again it is important to distinguish between the developed and the developing countries. The population of the industrialized nations is much older. Young people represent a small and shrinking fraction of the labor force, while the proportion of retirees over sixty-five is climbing. By 2000, fewer than 40 percent of workers in countries such as the United States, Japan, Germany, and the United Kingdom will be under age thirty-four, compared with 59 percent in Pakistan, 55 percent in Thailand, and 53 percent in China. (See Exhibit 4.)

The age distribution of a country’s workforce affects its mobility, flexibility, and energy. Older workers are less likely to relocate or to learn new skills than are younger people. Countries and companies that are staffed with older workers may have greater difficulty adapting to new technologies or changes in markets compared with those staffed with younger workers.

By 2000, workers in most developing nations will be young, relatively recently educated, and arguably more adaptable compared with those in the industrialized world. Very young nations that are rapidly industrializing, such as Mexico and China, may find that the youth and flexibility of their workforces give them an advantage relative to their industrialized competitors with older workforces, particularly over those in heavy manufacturing industries, where shrinkage has left factories staffed mostly with workers who are in their forties and fifties.

Most industrialized nations will have 15 percent or more of their populations over...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- ACKNOWLEGMENTS

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- PART 1

- SECTION 1

- 1 GLOBAL WORKFORCE 2000

- 2 TRAVELS INTO AMERICA’s FUTURE

- 3 THE NEW FACE OF AMERICA

- SECTION 2

- 4 DON’T NEGLECT THE IMPROVERISHED SOUTH

- 5 THE DANGERS OF DECADENCE

- SECTION 3

- 6 GRASSROOTS POLICYMAKING

- 7 DIVERSITY IN U.S. FOREIGN POLICYMAKING

- 8 THE FOS OF TOMORROW

- 9 A HOUSE DIVIDED

- SECTION 4 THE POLITICS OF MULTICULTURALISM IN INTRENATIONAL AFFAIRS

- 10 THE EROSION OF AMERICAN NATIONAL INTREST

- 11 MULTICULTURAL FOREIGN POLICY

- 12 OLL POILITICS ARE GLOBAL

- 13 GETTING UNCLE SAM’s EAR

- PART 2

- SECTION 5 HISPANIC AMERICANS AND U.S. FORIGN POLICY

- 14 THE KEENEST RECRUITS TO THE DREAM

- 15 FAMILY TIES AND ETHINIC LOBBIES

- 16 INTERNATIONAL INTERESTS AND FORIGN POLICY PROPERTIES OF MEXCAN AMERICANS

- 17 DATELIUNE WASHINGTON

- 18 HERE TO STAY

- SECTION 6 ASION AMERICANS AND FORIGN POLICY

- 19 BRIDGES ACROSS CONTINENTS

- 20 SLANTED

- SECTION 7 JEWISH AMERICANS AND FORIGN POLICY

- 21 THE GENESIS OF THE SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND ISRAEL,1948–1973

- SECTION 8 ARABN AMERICANS,MIDDLE EASTERN AMERICANS, AND U.S. FORIGN POLICY

- 22 LOCAN POLITICS IS GLOBAL, AS HILL TURNS TO ARMENIA

- 23 AMERICAN FORIGN POLICY IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND ITS IMPACT ON THE IDENTITY OF ARAB MUSLIMS IN THE UNITED STATES

- 24 HOW TO DEFINE A MUSLIM AMERICAN AGENDA

- 25 ARAB AND MUSLIM AMERICA

- SECTION 9 AFFRICAN AMERICANS AND U.S. FORIGN POLICY

- 26 CITIZEN DIPLOMACY AND JESSE JACKSON A CASE STUDY FOR INFLUENCING U.S. FORIGN POLICY TOWARD SOUTHERN AFRICA

- 27 AFRICAN AMERICAN PRESPECTIVES ON FORIGN POLICY

- 28 THE AFRICAN GROWTH AND OPPORTUNITY ACT

- PART 3

- SECTION 10 HUMAN RIGHTS AND GENDER IN U.S. FORIGN POLICY

- 29 HUMAN RIGHTS IN U.S. FORIGN POLICY

- 30 GENDER AND THE FORIGN POLICY INSTITUTIONS

- SECTION 11

- 31 BOWLING TOGETHER

- 32 POLITICS AFTER SEPTEMBER 11

- 33 LIBERAL DEMOCRECY VS. TRANSNATIONAL PROGRESSIVISM

- SECTION 12 CONCLUSION

- DOUBLE DIVERSITY

- CREDITS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Diversity and U.S. Foreign Policy by Ernest J. Wilson, III in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.