- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Flashbulb Memories

About this book

This book provides a state-of-the-art review and critical evaluation of research into 'flashbulb' memories. The opening chapters explore the 'encoding' view of flashbulb memory formation and critically appraise a number of lines of research that have opposed this view. It is concluded that this research does not provide convincing evidence for the rejection of the encoding view.

Subsequent chapters review and appraise more recent work which has generally found in favour of the flashbulb concept. But this research too, does not provide unequivocal support for the encoding view of flashbulb memory formation. Evidence from clinical studies of flashbulb memories, particularly in post-traumatic stress disorder and related emotional disturbances, is then considered. The clinical studies provide the most striking evidence of flashbulb memories and strongly suggest that these arise in response to intense affective experiences. Neurobiological models of memory formation are briefly reviewed and one view suggesting that there may be multiple routes to memory formation is explored in detail. From this research it seems possible that there could be a specific route for the formation of detailed and durable memories associated with emotional experiences. In the final chapter a cognitive account of flashbulb memories is outlined. This account is centred on recent plan-based theories of emotion and proposes that flashbulb memories arise in responses to disruptions of personal and cultural plans. This chapter also considers the wider functions of flashbulb memories and their potential role in the formation of generational identity.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

The Flashbulb Memory Hypothesis

In the 1970s two researchers, Roger Brown and James Kulik (1977), became interested in reports of surprisingly detailed and vivid memories for learning the news of certain prominent public events. The clarity and persistence of these memories were so striking that Brown and Kulik named them flashbulb memories (FMs). Informal evidence of the ubiquity of FMs emerged in an article from the popular magazine Esquire (1973), in which a number of celebrities recounted their memories of learning the news of the assassination of the American President John F. Kennedy that had occurred some 10 years prior to the Esquire interviews. What aroused Brown and Kulik’s interest was not the fact that the celebrities were able to recall that JFK had indeed been assassinated, but rather that they also recalled, often in minute detail, their personal circumstances when learning of the assassination (see Yarmey & Bull, 1978, for a detailed study of JFK FMs). They remembered what they were doing, who they were with, where they were, and each account also contained a number of idiosyncratic details of the type that are usually rapidly and completely forgotten. In order to gain some perspective on the remarkable durability and specificity of FMs, consider the following memory accounts reported (and partly corroborated) in a recent Independent Television (ITV) programme on British television commemorating the 30th anniversary of JFK’s assassination (Where were you’?, ITV, 22 November 1993):

Terry Lancaster, Foreign Editor (1963), Daily Express:

I got to the foreign desk and found a scene of amazing confusion and tension. Now I’d given up smoking that day—I gave up smoking fairly frequently—so the moment that I heard that Kennedy was dead I took off my coat and sent my secretary out for three packets of cigarettes.

Ludovick Kennedy, Writer and Broadcaster:

I was on my way home from the studios at Lime Grove and I had the wireless on and I heard this announcement, which was breaking into whatever programme was on, that he’d [JFK] been shot and I remember as I heard those words I said aloud, I was quite alone in the car, I said aloud “Oh no, Oh, no”.

Gerry Anderson, Film Producer:

I was with my ex-wife in a West End cinema when I became aware of something going on behind me and I turned round and I could see people in the back row of the balcony chatting busily to each other and even talking to the people in the row in front of them and I guessed that something pretty dreadful had happened—and you know the way today at football matches people create the “human wave” which moves across the stadium? Well in the same way the ripple came down the balcony and eventually I said to the man behind me “What’s happened?”, and he said “Kennedy’s been assassinated”.

And for an account which is strikingly detailed, possibly because of the intersection of the news with the rememberer’s ongoing interests at the time:

Derek Waken, Teacher:

I finished teaching about 4 o’clock and I thought between 4 and 6 I would take some cadets shooting on the range. So we went up with at least 4 if not 8 cadets and a captain of shooting, a young chap called Cameron Kennedy, and against all the rules I asked him if he’d lock up so I gave him the armoury keys, the magazine keys, and the ammunition and I left because the next day was Saturday and there was going to be a film so I thought I’ll thread up the first spool now. Suddenly one of the auditorium doors opened, light flooded in and a small boy standing there in silhouette shouted “Sir, Sir, Kennedy’s been shot!”. With that he disappeared. Then I switched off the light and set off rather slowly, could have been thinking about alibis I suppose, set off slowly for the sort of Matron’s area of the school, and I didn’t like to ask her directly and so I said “Matron, is there anything I should know?”, and she said “Yes, President Kennedy’s been shot”. Whereupon the weight was off me, I’d got my job back, and I was extremely happy.

These memories retained over a 30-year period and the memories reported in the Esquire article are unusual on three counts. First, they preserve knowledge of personal circumstances when learning of a public occurrence. Second, they are highly detailed and feature knowledge of minutiae not present in most autobiographical memories associated with news events (Larsen, 1992). Third, the memories endure in apparently unchanged form for many years. In order to account for these unusual memories, Brown and Kulik (1977) conducted their own investigation into FMs and developed a model of the function and formation of FMs—the flashbulb memory hypothesis (FMH). The purpose of this initial chapter is simply to describe Brown and Kulik’s (1977) original findings and to outline the FMH. Later chapters examine criticisms of the FMH, appraise subsequent studies, examine FMs arising from personal experiences rather than public events, and review current neurological findings relating to FM formation. The closing chapter assesses how the FMH has fared in the face of fairly persistent criticism and how it might be developed to encompass the broader range of current findings.

The Flashbulb Analogy

Brown and Kulik (1977) introduced the term “flashbulb” memories to convey the notion that these types of memories preserve knowledge of an event in an almost indiscriminate way—rather as a photograph preserves all the details of a scene. However, Brown and Kulik did not intend that the analogy between FMs and photographs be taken literally. Instead, they argued that although FMs often featured the recall of minutiae, they were, nonetheless, incomplete records of experienced events. Indeed, rather than emphasising the completeness of FMs, Brown and Kulik drew attention to what they called the “live” quality of FMs, in which only some perceptual and other details of an event come to mind with great vividness and clarity. In order to illustrate both the clarity and the incompleteness of FMs, Brown and Kulik provided descriptions of their own memories for learning of JFK’s assassination:

I was on the telephone with Miss Johnson, the Dean’s secretary, about some departmental business. Suddenly, she broke in with: “Excuse me a moment: everyone is excited about something. What? Mr Kennedy has been shot!” We hung up, I opened my door to hear further news as it came in, and then resumed my work on some forgotten business that “had to be finished” that day (Brown).

I was seated in a sixth-grade music class, and over the intercom I was told that the president had been shot. At first, everyone just looked at each other. The class started yelling, and the music teacher tried to calm everyone down. About ten minutes later I heard over the intercom that Kennedy had died and that everyone should return to their homeroom. I remember that when I got to my homeroom my teacher was crying and everyone was standing in a state of shock. They told us to go home (Kulik).

These accounts clearly convey the “live” quality, high definition and clarity of the memories from which they are derived. They also illustrate, however, the incomplete nature of the underlying memories (e.g. the forgotten departmental business in Brown’s account) and as Brown and Kulik (1977, p. 75) point out, other details such as the teacher’s dress in Kulik’s memory are also not available. Thus, FMs, although unusually clear and detailed, differ from photographs in that they do not indiscriminately preserve all the features of an event but, as we shall see, they do preserve certain common event features.

Factors Influencing Flashbulb Memory Formation

In order to investigate how FMs are formed, Brown and Kulik (1977) conducted the first formal FM study. They started with two intuitions. The first, based on the JFK assassination, was that the public event had to be unexpected and novel and, therefore, surprising. The second was that different events would vary in their consequentiality or significance for different sub-groups within society. For instance, the assassination of the civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King was certainly consequential for Black North Americans and so should be associated with a high frequency of FMs in this group. Brown and Kulik suspected that this event would be less consequential for White North Americans and, accordingly, that there would be a lower frequency of FMs in this group. For their study, Brown and Kulik selected nine surprising public events, some of which they assumed would vary in consequentiality for Black and White groups of subjects and others which should have the same effect for both groups. The nine events were: the assassinations of Medgar Evers, John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, the attempted assassinations of George Wallace and Gerald Ford, the scandal associated with Ted Kennedy, and the death of General Francisco Franco. A tenth event required recall of a private event featuring an unexpected personal shock.

In Brown and Kulik’s study, subjects answered “Yes” or “No” to the question “Do you recall the circumstances in which you first heard that …?” (obviously the wording of this question was changed slightly for the tenth “personal” event). When subjects answered “Yes”, they were then required to write an account of their memory and this could take any form and be of any length. Note that following Larsen (1992), memory for one’s personal circumstances when learning of an item of news will, hereafter, be referred to as memory for the reception event. Memory for a reception event should not be conflated with memory for an actual item of news and this is because the representation of public events in long-term memory (cf. Brown, 1990) differs from that for reception events. After describing each reception event, the subjects then rated the consequentiality of the item of news on a 5-point scale, where a 1 indicated “little or no consequentiality for me” and a 5 indicated “very high consequentiality for me”. For this rating of consequentiality, each subject was instructed to judge the consequentiality of the event for his or her own life. Specifically, they were instructed: “Probably the best single question to ask yourself in rating consequentiality is ‘What consequences for my life, both direct and indirect, has this event had?’ “(Brown & Kulik, 1977, p. 82). They were further instructed to consider how things might have gone, in their own lives, if the original event had not occurred. Brown and Kulik emphasise that they devoted considerable effort in communicating to subjects that it was the personal consequentiality or personal importance of the news item that should be assessed and not its wider national, international or historical significance. Finally, subjects also estimated their overt rehearsal of the memories and rated, on a 4-point scale, how frequently they had given an account of each reception event: “never told anyone”, “gave the same account 1 to 5 times”, “gave the same account 6 to 10 times”, “gave the same account more than 10 times”.

In order to score the memory descriptions of the various reception events, Brown and Kulik studied a subset of the accounts and developed a coding scheme that they then independently applied to the whole set. In developing the coding scheme, they identified six categories of information that were common to the memories in their sample and these were place, ongoing event, informant, affect in others, own affect and aftermath. In the case of memory accounts relating a personal unexpected shock, the category affect in others was rarely present, although all the other categories were present as were four new categories: event, person, cause and time. These additional categories specify information implicit in the other nine events. So pervasive were the categories of place, ongoing event, informant, affect in others, own affect and aftermath that Brown and Kulik referred to them as the “canonical” categories of recall. Using this coding scheme, an event was classified as a FM if the subject answered “Yes” to the initial question and then provided detailed information on one or more of the canonical categories. When the authors then independently classified the memory accounts and the separate classifications were compared, a high degree of consensus was observed with exact agreement on 90% of the classifications.

Before turning to a full account of Brown and Kulik’s findings, it is worth noting the type of information in the FM descriptions. This information was highly detailed and, although classed within one of the six general canonical categories, was specific to individual subjects, for example having a conversation with a classmate at Shaw University, talking to a woman friend on the telephone, having dinner in a French restaurant, and so on. Many of the accounts also included idiosyncratic event features which did not fit any of the canonical categories but that nonetheless demonstrated the fine grain of memory details in FMs. For example, comments such as “the weather was cloudy and grey”, “she said ‘Oh God! I knew they would kill him’”, “we all had on our little blue uniforms”, and “I was carrying a carton of Viceroy cigarettes which I dropped”, constitute a type of highly specific event detail rarely present in memory for most news events and, indeed, comparatively infrequent in everyday autobiographical memories (for reviews of, and recent findings in, autobiographical memory, see Conway, 1990; in press; Conway & Rubin, 1993; Conway, Rubin, Spinnler, & Wagenaar, 1992; Rubin, 1986; in press). These idiosyncratic event details lend support to Brown and Kulik’s claim that FMs have a “live” quality.

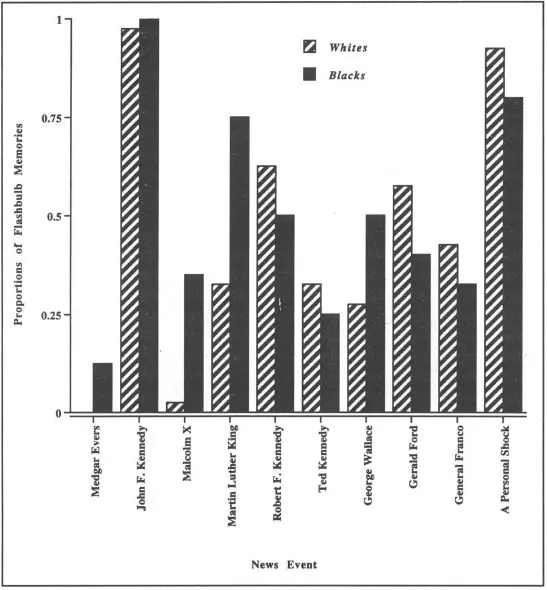

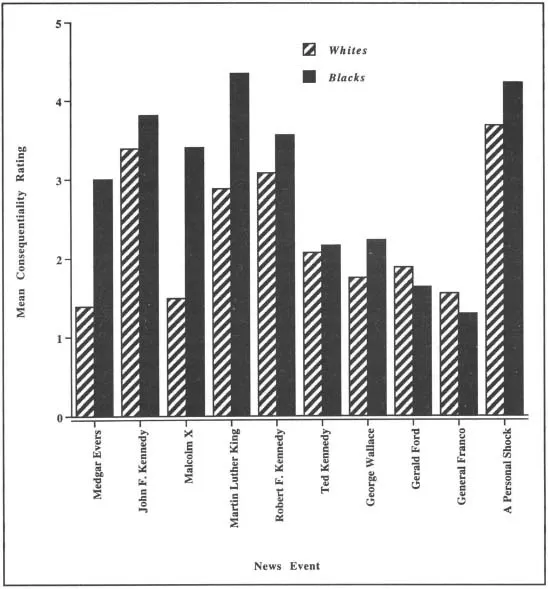

What then of the incidence of FMs across the subject groups for the different items of news? Figure 1.1 shows the proportions of subjects classified as having FMs to the various news events. The incidence of FMs across groups differed on only four of the events and the frequency of FMs was significantly higher for Blacks than Whites for the murders of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, and the attempted murder of George Wallace. For the first three of these events, the differences are marked. For instance, none of the Whites could recall the reception event in which they learned of the news of the murder of Medgar Evers, only one White had a FM for the murder of Malcolm X, and although a third of the Whites had FMs for the murder of Martin Luther King, this was far less than the Blacks, three-quarters of whom had FMs for this event. This aspect of the findings fits well with Brown and Kulik’s proposal that the personal consequentiality of an item of news is an important precondition to the formation of FMs. Further evidence for this was also present in the ratings of personal consequentiality of each news item and mean consequentiality ratings across groups are shown in Fig. 1.2.

Fig. 1.1. Frequency of flashbulb memories to 10 events (data from Brown & Kulik, 1977, table 2).

Fig. 1.2. Mean consequentially ratings for 10 events (data from Brown & Kulik, 1977, table 3).

It can be seen from Fig. 1.2 that Blacks rated the murders of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, and the attempted murder of George Wallace, higher in personal consequences than Whites and these differences were found to be reliable. Although a higher incidence of FMs and higher consequentiality for Blacks than Whites to learning the news of the murders of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were expected, the same pattern of differences for the attempted murder of George Wallace, a right-wing white politician, appears slightly unusual. However, as Brown and Kulik point out, Governor Wallace’s far-right stance on civil rights and racial issues made him a more significant figure for the Blacks than the Whites and the consequences of his retirement from the political arena would undoubtedly have been more consequential for Blacks than Whites. Thus, the incidence of FMs to the news of the attempted assassination of George Wallace also fits well with the consequentiality hypothesis.

Of the other events shown in Fig. 1.1,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. The Flashbulb Memory Hypothesis

- 2. The Case Against Flashbulb Memories

- 3. Evidence for Flashbulb Memories

- 4. “Real” Flashbulb Memories and Flashbulb Memories Across the Lifespan

- 5. The Neurobiology of Flashbulb Memories

- 6. Revising the Flashbulb Memory Hypothesis

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Flashbulb Memories by Martin Conway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.