Chapter One

Introduction:

Defining American Urbanism

The recent movement known as ‘New Urbanism’ is attempting to reconcile competing ideas about urbanism that have been evolving in America for over a century. New Urbanism, an urban reform movement that gained prominence in the 1990s, seeks to promote qualities that urban reformers have always sought: vital, beautiful, just, environmentally benign human settlements. The significance of New Urbanism is that it is a combination of these past efforts: the culmination of a long, multi-faceted attempt to define what urbanism in America should be. This revelation only comes to light in view of the history that preceded it.

This book puts New Urbanism in historical context and assesses it from that perspective. Analytically, my goal is to expose the validity of New Urbanism’s attempt to combine multiple traditions that, though inter-related, often comprise opposing ideals: the quest for urban diversity within a system of order, control that does not impinge freedom, an appreciation of smallness and fine-grained complexity that can coexist with civic prominence, a comprehensive perspective that does not ignore detail. Amidst the apparent complicatedness, history shows that divergences boil down to a few fundamental debates that get repeated over and over again. This means that American urbanism has endured a habitual crisis of definition. The question now is whether New Urbanists have seized upon the only logical, necessarily multi-dimensional definition of what urbanism in American can be.

My method is to summarize the connections and conflicts between four different approaches to urbanism in America. I call these approaches urbanist ‘cultures’ - a term I apply unconventionally - and use them to trace the multi-dimensional history of ideas about how to build urban places in America.1 There are obvious inter-dependencies, but at the same time, these cultures have struggled to connect with each other. This has led to a fragmented sense of what urbanism in America is, namely, a lack of connection among proposals that could be fashioned in a more mutually supportive way, and a poor conceptualization of the multi-dimensionality of urbanism.2

What has gradually evolved in the American experience are different approaches to creating good urbanism in America. Some have focused on small-scale, incremental urban improvement, like the provision of neighbourhood parks and playgrounds. Some have had larger-scale visions, drawing up grand plans and advocating for new systems of transportation and arrangements of land use. Others have looked outside the existing city, focusing on how to build the optimal, new human habitat. And some have emphasized that urbanism should be primarily about how the human settlement relates to ‘nature’. Multiple meanings of urbanism have, for over a century, been forming in the minds of American planners, architects, sociologists, and others who have endeavoured to define in specific terms what urbanism in America is or should be.

Each of these approaches can be seen to have its own predictable and recurrent cultural biases. Further, the inability to integrate these cultures better has impeded our progress for reform and created a situation of stalemate in which efforts to stem the tide of antiurbanism in the form of sprawl and urban degeneration remain painfully slow. At the same time, the recurrence and overlap of ideals is one reason why New Urbanism has had such a strong appeal.

Urbanism in American society generally has an ambiguous meaning. Urbanism may simply be defined as life in the big city, or more pejoratively, as the antithesis of nature. There is often a line drawn in the sand of the American consciousness - places are either urban, meaning downtown, or they are sub-urban or rural, meaning less than urban. Yet urbanism defined as big city life is a narrow definition that is not particularly helpful for rectifying the problems of American settlement, either for locations within the existing city or for new developments outside of it. Understanding the American take on urbanism involves much more than density calculations or the square footage of concrete.

New Urbanists have used many of these ideas in their attempt to consolidate a more complete and nuanced definition of American urbanism. Their definition tries to establish a framework for settlement, an integrated, inclusive way of thinking about urbanism. They have recognized that urbanism is not a certain threshold of compactness, a measure of density, or a condition of economic intensity. They have also learned that this makes the attempt to define it much more difficult.

My definition of American urbanism is simply this: it is the vision and the quest to achieve the best possible human settlement in America, operating within the context of certain established principles. To bring these ideals together within one framework - as the New Urbanists are attempting - it is important to recognize that there are essential principles that are recurrent and embedded in the historical American consciousness. In other words, while urbanism in America involves multiple concepts, it is not ‘anything under the Sun’. There is a recurrent normative content, and the interrelated history of ideas about what the best possible human settlement in America should be reveals this. As this book will demonstrate, these recurrent principles consist of, for example, diversity, equity, community, connectivity, and the importance of civic and public space.

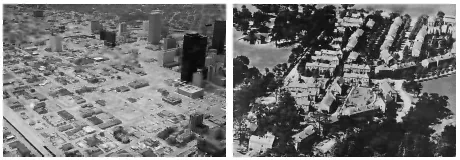

Figure 1.1. What is more ‘urban’? Contrasting perspectives on what can be used to define American urbanism. Left: downtown Houston, TX (Source: Landslides Aerial Photography). Right: Chatham Village, Pittsburgh, PA (Source: Clarence Stein, Toward New Towns for America, 1957).

Converse principles also exist - separation, segregation, planning by monolithic elements like express highways, and the neglect of equity, place, and the public realm. I bluntly label these ‘anti-urbanism’, and make a case for this interpretation in Chapter 2. Establishing this difference is necessary because a multi-faceted conception of urbanism cannot coalesce successfully unless it adheres to some basis of commonality. This does not necessarily eliminate conflict, but it does allow the possibility for seemingly conflicting ideas about good human settlement to be drawn together within the same framework. The concepts of urbanism that I review in this book are therefore considered as part of something larger, each forming their contributory part of a broader definition.

But there is a problem in that our current conceptualization of urbanism in America does not take this multi-dimensionality into account. The common critique that ‘New Urbanism is simply New Sub-Urbanism’ is symptomatic of this problem, and has a history to it. Lewis Mumford and his regional planning colleagues in the 1920s were horrified at the metropolitan ‘drift’ (outward expansion) being proposed for New York City, but their alternative - the decentralization of population into self-sufficient garden cities - was often mistaken for suburban land subdivisions and landscape gardening. Mumford thought anyone who mistook their proposals for mere suburbs had to be ‘deaf and blind’ since his organization, the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA), was proposing complete settlements, not single-use collections of single-family houses (Schaffer, 1988, p. 179). Still, the RPAA was always at great pains to make the distinction - exactly as New Urbanists are today.

By tracing the multiple historical concepts to which New Urbanism is linked, I am hoping to create a more complete and detailed view of American urbanism. This is important because the failure to nuance what is meant by urbanism in an American context has created a dichotomy that may be detrimental to the goal of establishing a better pattern of settlement. There are divisions between those who would focus only on the existing city, or only on urban containment, versus those content to focus on creating new externally situated settlements. Where overlap and complementarity (i.e., synergies) exist, they are not always exploited. If urbanists - primarily planners and architects - are constantly arguing among themselves about the true and legitimate definition of urbanism in America, they undercut the synergies that could be capitalized on. These are precisely the synergies the New Urbanists have attempted to rally. But to accept their strategy requires a much more sophisticated idea about what urbanism is supposed to be.

This is not about justifying suburbia. Nor is it about insisting that suburbs, no matter what their form, be included as essential parts of the city, as some have done (see, for example, Sudjic, 1992). On the contrary, this book is about discerning how urbanism in America is translated from different perspectives. It is about articulating a multi-dimensional view of American settlement that rises to the level of urbanism in a variety of contexts. That level can, in my view, exist in locations outside of downtown cores - meaning suburban locations. Since, in the 1920s, America was already growing twice as fast in the suburbs as in the central cities, this is hardly a radical idea.

There are tactical reasons for taking this approach: most Americans live in suburbs and in single-family homes. Suburbs account for an enormous amount of what we consider to be ‘urbanized area’ in the U.S., making their ambiguous relationship with the notion of ‘urbanism’ all the more disjointed. Suburbs are part of the evolution of American urbanism, and that means that many of them can be seen as an inchoate form of urbanism. And some suburbs were composed of the essential elements of urbanity from the start - diversity, connectedness, a public realm. It makes sense, therefore, to pay particular attention to those suburbs that have something positive to offer in our quest to define what urbanity is, despite the fact that they have been labelled sub-urban. It seems reasonable then to develop a definitional language of urbanism that fits the suburban context and that may help them evolve in a way that is more positive.

I attempt to get at this by focusing in particular on what city planners and urban activists have come up with over the past century. In the shadow of repeated disappointment with our physical situation - a commonly despoiled landscape -Americans have continuously laboured to find the ‘right’ way of American settlement. We have been looking for an approach to building our urban places in a variety of contexts and scales - streets, neighbourhoods, towns, villages, suburbs, cities, regions, and, despite our meagre success at building according to plan, this quest to define American urbanism has never diminished. It is this fact - the persistence of an American teleology when it comes to urbanism - that translates the endeavour of making urbanist proposals from mere utopian dreaming into something more substantial.

This history of urbanism, which functions as a history of New Urbanism, reveals that there are multiple viewpoints, romanticist and rationalist approaches, different ideas about control and freedom, about order and chaos, about optimal levels of urban intensity. There are debates about the relationship between town and country, between two-dimensional (maps and plans) and three-dimensional (buildings and streetscapes) contexts, between empirical and theoretical insights, between the role of the expert and the place of public participation.

My analysis of American urbanism incorporates the existing character of cities and city life, but I am focusing primarily on what we aspire toward. It is a distinction between understanding why urbanists propose what they do and how they go about getting it, versus understanding only the latter. My view of urbanism, as in cultural theory, is that both understandings are needed (Thompson, Ellis and Wildavsky, 1990). We need to know why preferences are formed as well as how and whether goals are achieved because this gives a more complete picture. It is also essential for understanding urbanism, since the quest to build the ‘best’ human settlement is often more about aspiration than accomplishment.

Thus, I am particularly interested in what we think urbanism in America should be as opposed to attempting to measure only what we have achieved, important as that question is. This is nothing more complicated than the quest to make good cities, and to do so with specific ideas about ends and purposes. But it is not an analysis of lost dreams or utopianism. Countless ideas and plans remain unrealized, but that does not mean they are inconsequential - even seemingly abstract theories generated by intellectuals can have tremendous impact on actual practice, for example in the way Emil Durkheim’s theories became a basis for urban renewal (Schaffer, 1988, p. 233). The impact of ideas about urbanism may be appropriately measured by the degree to which they continue to inspire and effect city planning. Because ideas are not formed in a vacuum but rather within a political context, they are on some level a reflection of what Americans think about their forms of settlement. Admittedly, this does not necessarily mean they are based on public consensus: the degree to which urbanist ideals are based on direct citizen input varies widely. The point is that a history of what we aspire towards should not be viewed as somehow existing apart from reality.3

I think a more concerted effort to define American urbanism is justified given the rather loose way in which the term has been used in the U.S., and given the fact that there is no official definition of it in any case. It is a term that can legitimately be seen as being fluid, not only because it describes a variable state of being, but also because the multiple traditions impacted upon it are so strong. Neither is it useful to get lost in various technical meanings and usages of the term urbanism. This is exactly what happened at the first meeting of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (International Congresses of Modern Architecture), known as CIAM, in 1928, where some thought the word incomprehensible and wanted to use instead ‘City and Regional Planning’ (Mumford, 2000, p. 25).

Accordingly, self-proclaimed ‘urbanists’, from the Communist ‘urbanists’ of the 1930s to the ‘New Urbanists’ of the 1990s, have been critiqued for not living up to the requirements of the term, however that was defined. Starting with a more inclusive sense of the term, we can at least start with the notion that ‘urban’ is related to ‘city’, and that the idea of a city was not originally based on anything more specific than a community of citizens living together in a settlement.4

Four Urbanist Cultures

In seeking a better definition of American urbanism, a key question is why these common principles - for example, diversity, community, accessibility, connectivity, social equity, civic space - have not coalesced into a more united front when it comes to employing the principles of urbanism. One way to get at this is to explore how these enduring, overlapping or potentially complementary principles have fared under different planning regimes. What happens when they are approached in different ways, under different constraints and legalities, with different levels of political commitment, different methodological insights, different participation rules, different notions of fairness? What happens under different implementation realities and measures of success and failure?

My survey of the past one hundred or more years of urbanist ideals reveals four separate strains that I call incrementalism, plan-making, planned communities, and regionalism. These are the four ‘cultures’ of American urbanism, four approaches to city-making, constituting four sets of debates, critiques, counter-critiques, successes and failures. Each has built up its own culture, in a sense, with its own set of cultural biases. Each culture has its own unique story to tell, its own contribution to make to the story of American urbanism.

The four strains, or cultures, vary in their level of intensity and sense of order (explained more fully in Chapter 2). Concisely, incrementalism is about grass roots and incremental change; plan-making is about using plans to achieve good urbanism; planned communities focus on complete settlements; and regionalism looks at the city in its natural, regional context. Their differences are substantive and procedural, and they are sometimes empiricist and sometimes rationalist.5 They differ in their relationship to existing urban intensity and notions of order, but ultimately, American urbanism depends upon all of these dimensions and perspectives, varying as they do in their level of specificity, scale and approach.

In my analysis of these four cultures, I look for the essence of their principles - the underlying causes of their approval or disdain. Each strain has vehement supporters and vehement opponents, and I am most interested in trying to understand the underlying dimensions of these views. Many times, it is the instance where they veer away from urbanistic thinking that forms the basis of their critique. I conceive of the struggles surrounding these four cultures as important for revealing what American urbanism is trying to be.

I see it as somewhat tragic that most ideas about how to build a better settlement in America - how to help the inner city, stop sprawl, save the environment, manage traffic, support schools, and all the other myriad issues related to city building - are so recurrent. There is a need for a wider recognition that ideas for improving the American city came from somewhere, and that they have been similarly critiqued and debated many times before. Freedom, control, diversity, order, plurality, community - none of these are new to the American city-making debate. It is important to realize their tenacity at irresolution, and get to work on the essential task of finding more creative ways forward. We may decide that it is necessary to reframe the debate, or that the debate itself is a necessary part of city-making, or even that there is no resolution for a given issue. Perhaps every generation will need to revisit the same issues and debate them each time in their own way. But at a minimum, we should be engaging in these debates in full knowledge of how they were framed, resolved or unresolved in the past. Such an effort is bound to produce a more enlightened discourse.

Multi-Dimensionality

In city planning history, the attempt to fashion an interconnected set of ideas, joined together to create a coherent basis for American urbanism, goes against the usual view, described by Jencks, that approaches to urbanism are more reminiscent of the ‘wandering drunk’ than a ‘cumulative tradition’. The question I raise is whether aspects of several different approaches can in fact be forged together to create a multi-dimensional project that is the essence of American urbanism, now organized as New Urbanism. It requires the ability to look at divergent ideas and, rather than seeing commonality merely on the basis of ‘agitated, sometimes apocalyptic, pursuit of new solutions’, seeing a more deeply rooted, substantive form of agreement (Jencks, 1987, p. 301). What this might be based on is what I have set out to discover.

The question to address is whether a coexistence of perspectives is a necessary condition of American urbanism. We can find interconnections, which would seem to help the case for multi-dimensionality. But running throughout the intertwined threads comprising American urbanism, there is a corresponding set of threads that weaken, or perhaps simply obscure the linkages. A clear example is needed to ground this analogy. One connecting thread is the idea of the neighbourhood. The concept of a localized, village-like, self-contained unit is pervasive and is present as a response to the industrial city from the beginning. John Ruskin had his version, and later William Drummond and Clarence Perry articulated it in American terms. The pervasiveness of the idea is understandable. The neighbourhood unit is service-oriented, socially-supportive, and attentive to human need. The problem is that, almost simultaneously, it came to be associated with something more sinister - the eradication of the existing city and the social diversity it contained. Ruskin’s programme called for total destruction and replacement wherever cities were less than works of art, while Perry advocated ‘scientific slum rehabilitation’ (Perry, 1939, p. 129). In any case, the seeming thread of the neighbourhood model of...