eBook - ePub

Distributed School Leadership

Developing Tomorrow's Leaders

Alma Harris

This is a test

Share book

- 178 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Distributed School Leadership

Developing Tomorrow's Leaders

Alma Harris

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The role of distributed leadership in sustaining educational change is a hot topic around the world

Concise, pithy book that includes case studies and practical advice for school leaders

Could become recommended reading for those school leaders and aspiring school leaders on NPQH courses

Well-known author with international reputation

Part of new series, with very high-quality authors

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Distributed School Leadership an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Distributed School Leadership by Alma Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Leadership in a Changing World

As models of leadership shift from the organisational hierarchies with leaders at the top to more distributed, shared networks, people will need to be deeply committed to cultivating their capacity to serve what’s seeking to emerge

(Senge et al, 2005:186)

Within each of the developed countries, including the United States, average life expectancy is five, ten or even fifteen years shorter for people living in the poorest areas compared to those living in the richest

(Wilkinson, 2005:1).

In today’s climate of rapid change and increasingly high expectations, effective leadership is needed more than ever. But the question is what type of leadership? It is clear that change on such a massive scale will demand new leadership practices but the precise forms of leadership required to grapple with the complexities and challenges of technological advancement and globalisation remain unclear. The increasing integration of world economies through trade and financial transactions has created emerging market economies that are more integrated and interdependent (Zhao, 2007). Economic globalisation has outpaced the globalisation of politics and mindsets (Stiglitz, 2006:25). The traditional economic boundaries between countries are rapidly becoming less and less relevant. The global economy is booming.

But globalisation has also become a crisis in many parts of the world (Zhao, 2007:18). Despite increasing levels of wealth and prosperity around the globe, relative levels of poverty are higher than ever before and the gaps between rich and poor are widening. As the economic market place of the world is changing, in both developed and less developed countries, there is an increasing disparity between those who have high quality education and those who do not.

Although the wealth of the most affluent nations has soared, there is a growing underclass of citizens living in poverty. In her book The Shock Doctrine, Naomi Klein (2007) asserts that poverty, misery and human suffering are a necessary part of new ‘disaster’ capitalism. She challenges how far the global free market has triumphed democratically and argues that America’s ‘free market’ policies have come to dominate the world – through the exploitation of disaster-shocked people and countries.

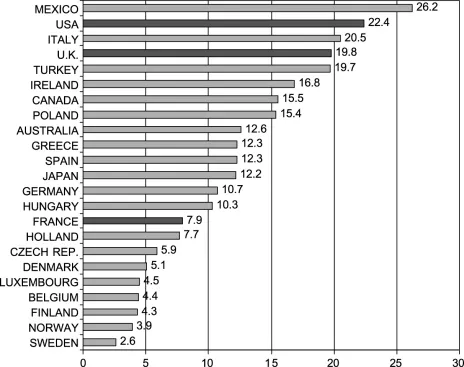

In his analysis of the relationship between poverty and educational attainment, David Berliner (2005) highlights the fact that the United States has the highest rate among industrialised countries of those that are permanently poor. As the Figure 1.1 below shows, only Mexico has a higher rate with the UK in fourth position with 19.8 per cent. Berliner (2005) also points out that many of the wealthy countries, like the USA and the UK, have few mechanisms to get people out of poverty once they fall into it. So those who become impoverished through illness, divorce, or job loss are likely to remain poor.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of children living in ‘relative’ poverty defined as households with income below 50 per cent of the national median income (UNICEF, 1999, http://www.unicef.org/.

While the rich have become richer, the poor have become poorer. Those who are well educated have access to the richest economic system the world has ever known. For those who lack education, the door of opportunity is ‘slammed shut’ (Barr and Parrett, 2007:7). As Berliner (2005:15) argues, ‘poverty restricts the expression of generic talent at the lower end of the socio-economic scale’. It is clear that poverty limits life chances as well as educational achievement.

The moral imperative to address issues of poverty is clear, so is the educational imperative. The gap between the educational attainment of the poorest and the most affluent students is getting larger, even though overall levels of performance may have increased. As Fullan (2006:7) argues, we urgently need to ‘raise the economic bar and close the gap between the richest and the poorest’. Clearly no one would disagree. But what kind of education will be required to close the gap, what kind of schools, what kind of leadership?

This book is primarily concerned with addressing the educational apartheid that separates the rich from the poor so starkly in terms of educational attainment. The book focuses particularly on school leadership as one means of improving learning for all students in all school settings. It argues that leadership is a powerful and important force for change in schools and school systems.

As the McKinsey (2007:71) report noted:

School reforms rarely succeed without effective leadership both at the level of the system and at the level of the individual schools. There is not a single documented case of a school successfully turning around its pupil achievement trajectory in the absence of talented leadership. Similarly we did not find a single school system which had been turned around that did not possess sustained, committed and talented leadership.

The main challenge facing schools and school systems is how to locate, develop and sustain committed and talented leadership. How do we find the leaders of tomorrow and keep them in our schools and school systems? How do we nurture, grow and develop broad-based leadership capacity in our schools?

This book suggests that to identify and develop the leaders of tomorrow is both urgent and necessary for system transformation. It suggests that to release the leadership capability and capacity in our schools we need to alter structures, redefine boundaries and remove barriers that prevent broad-based involvement of the many rather than the few in leadership. But it is more than just about changing structures. The most effective schools and school systems invest in developing leaders. They actively seek out leadership talent,1 and provide development opportunities for those in the very early stages of their career (Harris and Townsend, 2007).

In 2007 Finland was at the top of educational performance tables. Teaching in Finland is a high status profession with ten applicants for every teacher-training place. All school leaders teach and also take on a system-wide responsibility, supporting change and development in other schools. Within Finland, schooling is viewed as a public and not a private good and the school system is based upon the core values of trust, co-operation and responsibility.

In contrast the US and English school systems are based on high accountability mechanisms and low trust of teachers. Leaders in many schools are far too busy to teach, even if they wanted to. So how do we re-organise schools and school systems so that leaders are closer to learning? How do we re-engage with the moral purpose of education and produce tomorrow’s leaders who put learning before targets?

Closing the attainment gap will not be secured simply by providing more school leaders. This will only be achieved by ameliorating the negative and pervasive social and economic conditions that influence communities and the life chances of young people. Any attempts at educational improvement can only be part, and possibly only a small part, of the wider agenda of reducing social and economic inequalities in society (West and Pennell, 2003; Harris and Ranson, 2005).

We know that within school factors or influences cannot offset the forces of deprivation. However it is clear that schools can make a difference and do make a difference to the life chances of young people, particularly those young people in the poorest communities (Harris et al, 2006a, 2006b; Reynolds et al, 2006). Within all schools but particularly high-poverty schools, leadership is a critical component in reversing low expectations and low performance. The quality of leadership has been shown to be the most powerful influence on learning outcomes, second only to curriculum and instruction (Leithwood et al, 2006a, 2006b). The question is what type or form of school leadership is most likely to secure learning success for all children in all contexts?

This book takes a long, hard look at distributed leadership as one emerging form of leadership practice in schools. It examines distributed leadership from the perspective of theory, practice and empirical evidence. It explores whether distributed leadership has the potential to improve learning at the organisation and individual level. As Youngs (2007:1) has pointed out, ‘issues of popularisation mean that distributed forms of leadership may end up being yet another “fad”’. This is certainly true. It is important therefore to stand back and take a critical, informed and empirically based look at distributed leadership.

If distributed leadership is found to be little more than delegation, then we need to know that and move on. If it has the potential to broaden our understanding of school leadership and allows us to suspend and possibly relinquish our conventional and dominant views of leadership, it is worth pursuing. As Youngs (2007:1) points out, the latter will require courage. Distributing leadership within and across school and school systems requires a shift in power and resources. It demands alternative school structures that support alternative forms of leadership. Inevitably, this will generate some criticism, resistance and even derision from those with a vested interest in keeping things just the way they are.

But the pressure for change in school and school systems is now acute. There are many global, national and local trends that will necessitate significant changes in schools and schooling. Globalisation, changing employment opportunities and shifts in the pattern of recruitment of school leaders are powerful forces for change. They cannot be ignored. The pressure for change is relentless and unremitting.

As each of these forces for change is explored in the sections and chapters that follow, it is important to remember that the prime reason for thinking about alternative ways of organising schools and adopting different approaches to leadership is to make the learning experiences of all young people better. It is primarily concerned with the educational success of every student, irrespective of background or context.

The analysis of social, economic and global ‘change forces’ suggests that we urgently need new organisational forms and leadership practices within our schools and school systems. We cannot have twentieth century structures shaping twenty-first century leadership practices. But none of these change forces is as important as the moral purpose of education. Put simply, if we are committed to changing leadership structures and practices in our schools, we do it because we believe it will improve the learning and life chances of all our students.

Globalisation

As a force for change, globalisation is rapidly reshaping societies and cultures on a massive scale. Work is being redefined and organisational boundaries are being redrawn. The pace of change is relentless, even frantic, and the demands for improvements in schooling unprecedented. As Bernake (2006:833) points out, ‘rather than producing goods in a single process in a single location, firms are increasingly breaking the production process into discrete steps and performing each step in whatever location allows them to minimise costs’. Theoretically, a business can employ anyone, at any time, anywhere in the world. Outsourcing is now commonplace and millions of Chinese and Indians are working for US businesses located in any of the three countries (Zhao, 2007:832). The global market place is fast, complex and diverse.

Thomas Friedman (2006) talks about ten forces that have redefined and re-shaped the ‘flat world’ in the twenty-first century (Friedman, 2006:828). His basic argument is that the boundaries and barriers to global business have largely disappeared creating a flatter world and a more competitive environment. He points out that the type of leadership required in the ‘flat world’ is one that embodies creativity, flexibility, portability and ingenuity. It is a form of leadership that cannot be restricted by structures or organisational boundaries.

Despite such powerful global trends, leadership is still thought about in a rather traditional way. As Senge et al (2005) propose:

One of the road blocks for groups moving forward now is thinking that they have to wait for a leader to emerge – someone who embodies the future path. I think the key to going forward is nurturing a new form of leadership that does not depend on extraordinary individuals. (p 185)

Across all organisations the future competitive edge will be the creative edge. In all sectors, the premier organisations will be singled out by their ability to be transformative and innovative. Leadership will be required that will secure transformation and rapid change. Lightning-swift advances in technology and communication will undoubtedly create greater challenges for leaders and leadership. This is particularly true of schools.

As the link between individuals and their organisations is weakening, patterns of activity are shifting away from a central location and point of control. As organisational functioning becomes more geographically dispersed, it remains questionable whether existing leadership practice, particularly its hierarchical form, can survive. Senge et al (2005) suggest that ‘in a world of global networks we face issues for which hierarchical leadership is inherently inadequate’ (p 186). Their work suggests that as long as our thinking is governed by concepts from the ‘machine age’ we will continue to recreate institutions as they were in the past, and leadership practices suited for institutions belonging to another era.

Seeing leadership in a different way requires stopping our habitual ways of thinking about leadership and leadership practice. The capacity to suspend established ways of seeing is essential for allimportant scientific discoveries. It requires what Senge et al (2005:84) term ‘sensing an emerging future’, where old frameworks are not imposed on new realities. As the pace of technological development quickens, so does the rate of what Joseph Schumpeter (1942) has called the ‘creative destruction’ – of products, companies and even entire industries. Little is predictable or repetitive, and ‘overall businesses operate less and less like halls of production and more and more like a kind of casino of knowledge’ (Senge et al, 2005:84).

In his work, David Hargreaves (2007) argues that system leadership requires more than head teachers securing sustainable system-level change. He suggests that system redesign is needed to improve the architecture of schooling, and highlights how leadership is a powerful force of reconfiguration in the redesign of the system (Hargreaves, 2007:27). This leadership configuration has five components:

- flatter, less hierarchical staff structure;

- distributed leadership;

- student leadership;

- leadership development and succession;

- participative decision-making processes.

Hargreaves (2007) argues that these five components are already in place in many schools, and that system redesign will emerge as schools drive the process of transformation and change.

The educational environment has shifted so dramatically and so permanently that we need to reconsider what we understand by leadership and leadership practice in schools. In many countries, schools are no longer at the centre of educational provision. Multi-agency working, partnership and networks are the common denominators of contemporary educational change. They are demanding and creating alternative leadership practices. Inter-institutional collaboration and multi-agency working are also providing the platforms for new leaders to emerge. Support staff, parents, students and multi agency professionals are all potential leaders and change agents.

In the ‘brave new’ economic world, schools will need to harness all the available leadership capacity and capability. This will only be achieved if schools maximise all forms of human, social and intellectual capital. To maximise leadership capacity schools need to be operating and performing at the level of the best schools. To achieve this requires a radical shift in leadership practice.

Good to Great

In the opening line of his book Good to Great, Jim Collins (2001) states that ‘good is the enemy of great’, and argues that one of the reasons why we don’t have great schools is because we have good schools. The vast majority of our schools, he suggests, never become great because the vast majority become quite good. If we accept this argument and ask what it takes for schools to become ‘great schools’ rather than ...