- 450 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Oxidants, Antioxidants And Free Radicals

About this book

This volume collates articles investigating antioxidant, oxidant and free radical research. It examines the role of such research in health and disease, particulary with respect to developing greater understanding about the many interactions between oxidants and antioxidants, and how such substances may act as natural protectants and /or natural toxicants.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Oxidants, Antioxidants And Free Radicals by Steven Baskin,Harry Salem in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Biochemistry in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

REDOX, RADICALS, AND ANTIOXIDANTS

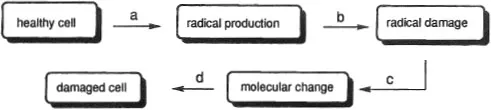

This chapter presents a synopsis of some radical-mediated processes, focusing on phenomena related to biochemistry and medicine. The importance of radicals in biological processes was recognized over a half-century ago (1). More recently, Willson has provided a convenient summary of the sequence of events involved in free-radical induced cell damage (Figure 1) (2). Since biological damage created by radicals often is associated with “oxidation”, the literature places more emphasis upon oxidations than reductions. Yet bear in mind that oxidation reactions are one-half of oxidation–reduction (redox) couples and that every oxidation is accompanied by a reduction.

Figure 1. Diminishing radical-induced cell damage: a = radical formation prevention; b = radical scavenging; c = radical repair; d = biochemical repair.

After a summary in this chapter of terminology dealing with oxidation and reduction, attention shifts to radicals since they are arguably the most important intermediates in medicine as well as in biological oxidation–reduction systems. Since oxygen-containing radicals play a substantial role in initiating tissue damage, these species are introduced in the next section. This is followed by an examination of some of the more widely investigated naturally occurring antioxidants, that is, L-ascorbic acid, β-carotene, vitamin E, and coenzyme Q. The chapter ends with a presentation of radical chain reactions and mechanisms whereby antioxidants can interfere with these processes. Strategies for antioxidant defense in living systems have been reviewed (3, 2, 3, 4, 5) and comparisons between natural and synthetic antioxidants made (6).

Given the vastness of the topic, the authors apologize to the many whose excellent work has been omitted because of limitations on chapter size.

THE LANGUAGE OF REDOX

Inorganic chemists frequently classify atoms within molecules by their oxidation number (ON) (7). An element with a given ON is described as having the “oxidation state” corresponding to that value and, while not strictly identical, these terms often are used interchangeably. An oxidation reaction can be described as one in which the oxidation number of an atom becomes more positive while reduction corresponds to it becoming less positive (or more negative).

Although a number of metals have more than one ON, one useful definition of a metal’s ON is the positive number equal to the charge on that metal’s oxide. Thus, the ON of zinc in zinc oxide (ZnO) is +2. Potent inorganic oxidants often contain metals with large, positive oxidation numbers. For example, the ON of manganese in the permanganate ion (MnO4-) is +7 while that of chromium in both chromate (CrO42-) and dichromate ions (Cr2O72-) is +6. After functioning as an oxidant, the ON of the metal becomes less positive, such as MnO4- becoming MnO2 or Mn2+ (ON of Mn = +4 or +2, respectively). Particularly large values (e.g., +7) do not represent the actual charge on a metal, with the true value being smaller due to “back bonding” to atoms associated with the metal. Consequently, these values sometimes are termed “formal” oxidation numbers. While metals often have an ON equal to their group number in the traditional periodic table, nonmetals have ONs equal to eight minus their group number. Like metals, nonmetals may exist with several ONs. For example, the ON for oxygen in water or alcohol is −2 but is −1 in molecules containing an –O–O– fragment, such as hydrogen peroxide, and −1/2 in superoxides. Hydrogen can have positive (+1 in water) and negative (−1 in metal hydrides) ONs. Regardless of an individual atom’s ON, the sum of the ONs of all elements in any neutral species must equal zero.

The application of ONs to organic molecules is more difficult. With alkanes, for example, the ON of carbon is obtained by dividing the total number of hydrogens by the number of carbons and assigning the value a negative sign. Thus the ON for methane’s carbon is −4 while for either carbon of ethane it is −3. It is −2.67 for the average carbon of propane, −2.5 for the average carbon of butane, and so on, although organic chemists do not commonly think of methane, ethane, propane and butane as having carbons in different states of oxidation. It may be more useful to consider the oxidation level of carbon as varying with the number of electronegative substituents to which it is bonded. Since the usual ON for any halogen is −1, the chlorination of methane, to yield chloromethane and hydrogen chloride, is an oxidation of methane since carbon’s ON goes from −4 to −3. However, while the conversion of methyl chloride to methanol creates a C–O bond, it is not considered an oxidation since the ON of carbon in both methanol and methyl chloride is −3.

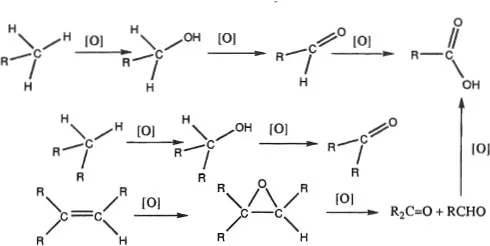

Rather than ONs, organic chemists think in terms of sets of functional groups arranged in order of increasing extent of oxidation (8). The oxidation reactions shown in Figure 2 involve an obvious increase in the amount of oxygen, or bonds to a given oxygen, in the compound undergoing oxidation.

Figure 2. Oxidation reactions in selected sets of functional groups.

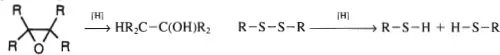

Oxidation also may be recognized by the loss of hydrogen from a molecule. Such dehydrogenations may either be intramolecular [e.g., the conversion of ethanol (C2H6O) to acetaldehyde (C2H4O)] or intermolecular (e.g., conversion of a thiol to a disulfide).

Reductions may be thought of as the reverse of oxidation and defined in terms of hydrogens becoming bonded to a molecule. The conversion of epoxide to alcohol (as follows) and the hydrogenation of a disulfide both involve reduction. Note that all of these definitions are based upon descriptive chemistry and not upon the mechanism of any given reaction.

In an electrochemical cell, oxidation corresponds to loss of electrons from the anode while reduction refers to a gain of electrons by the cathode. The same is true of a galvanic cell (9, 10).

RADICALS

A radical (“free radical”) is a species that possesses one or more unpaired (“odd” or “single”) electrons (11). While many radicals have a net charge of zero, those that carry both a charge and an odd electron are “radical ions” and may either be radical cations or radical anions (12). A molecule may lose or gain electrons singly or in pairs. One-electron transfer processes involve radicals (13). Two-electron transfers may involve either a simultaneous transfer of two electrons or two sequential one-electron transfers. Both one- and two-electron transfers occur in vitro (14) and in vivo (15). Indeed, it is likely that all living cells contain some odd-electron species.

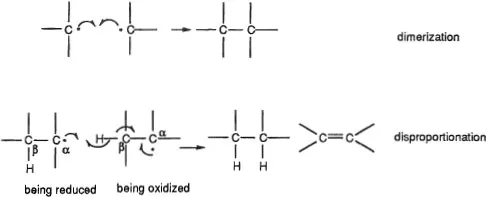

Most organic radicals have very short lifetimes. Without stabilizing features, such as steric hindrance at the odd-electron site and/or extensive delocalization of the odd electron, they decompose rapidly—even in the absence of external agents. Two routes that lead to this decomposition are dimerization and disproportionation. Disproportionation entails the simultaneous oxidation of one radical and reduction of another, frequently through the involvement of a hydrogen β to the carbon bearing the odd electron (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Usual decomposition pathways of radicals. Single-headed (“fishhook”) arrows depict movement of one electron. Their presence always indicates a radical reaction.

Two other reactions common to many radicals are (a) abstraction of a hydrogen atom from a nearby molecule and (b) a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributors

- About the Editors

- CHAPTER 1 Redox, Radicals, and Antioxidants

- CHAPTER 2 The Analysis of Free Radicals, Their Reaction Products, and Antioxidants

- CHAPTER 3 Vitamin E

- CHAPTER 4 Vitamin E and Polyunsaturated Fats: Antioxidant and Pro-oxidant Relationship

- CHAPTER 5 α-Tocopherol, β-Carotene, and Oxidative Modification of Human Low-Density Lipoprotein

- CHAPTER 6 Response of Antioxidant System to Physical and Chemical Stress

- CHAPTER 7 Zinc as a Cardioprotective Antioxidant

- CHAPTER 8 Ascorbic Acid, Melatonin, and the Adrenal Gland: A Commentary

- CHAPTER 9 Antioxidant Properties of Glutathione and its Role in Tissue Protection

- CHAPTER 10 Antioxidant Effects of Hypotaurine and Taurine

- CHAPTER 11 Antoxidative Activity of Ergothioneine and Ovothiol

- CHAPTER 12 The Toxicology of Antioxidants

- CHAPTER 13 Toxicity of Oxygen and Ozone

- CHAPTER 14 Peroxidation of Lipids and Liver Damage

- CHAPTER 15 Role of Free Radicals in Alcohol-Induced Tissue Injury

- CHAPTER 16 Oxidant Injury from Inhaled Particulate Matter

- CHAPTER 17 Edemagenic Gases Cause Lung Toxicity by Generating Reactive Intermediate Species

- CHAPTER 18 Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Depletion Induced by Blast Overpressure

- CHAPTER 19 Food Antioxidants: Their Dual Role in Carcinogenesis

- CHAPTER 20 Anticarcinogenic Effects of Synthetic Phenolic Antioxidants

- Index