- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Politics of Making

About this book

A unique collection of contemporary writings, this book explores the politics involved in the making and experiencing of architecture and cities from a cross-cultural and global perspective

Taking a broad view of the word 'politics', the essays address a range of questions, including:

- What is the relationship between politics and the making of space?

- What role has theory played in reinforcing or resisting political power?

- What are the political difficulties associated with working relationships?

- Do the products of our making construct our identity or liberate us?

A timely volume, focusing on an interdisciplinary debate on the politics of making, this is valuable reading for all students, professionals and academics interested or working in architectural theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Making by Mark Swenarton,Igea Troiani,Helena Webster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Watching Palaces

Ruskin and the representation of Venice

Stephen Kite

And as for these Byzantine buildings, we only do not feel them because we do not watch them; otherwise we should as much enjoy the variety of proportion in their arches, as we do at present that of the natural architecture of flowers and leaves.1

The 'watching' of buildings Ruskin stresses in Volume 2 of Stones of Venice entails a more urgent ethical scrutiny than merely 'looking'. Its etymology is Old English, related to the German wachen which involves the sense of watching-over or keeping vigil besides someone or something that is loved and needs protection. The following pages approach Ruskin's 'watching' through a close reading of his worksheets, diaries and notebooks (related to The Seven Lamps of Architecture and The Stones of Venice) and the stones themselves, to discover his representation of the city, and the ethical and ideological positions that underlie this.

The 'heart of the thing'

Ruskin singles out Gentile Bellini's panorama of a Corpus Christi Procession in Piazza San Marco (1496) as 'the perfectly true representation of what the Architecture of Venice was in her glorious time; ... its inhabitants and it together, one harmony of work and life ...'2 In The Seven Lamps of Architecture Ruskin writes of the 'distinctively political art of architecture';3 for him 'the built environment is the "political" environment by definition'.4 In human polity Ruskin saw decisions as commonly driven by expediency rather than any higher sense of reason: equally in architecture he censured an environment shaped by an accelerating materialism and limitless new functional demands. As a consequence he argued that it was imperative to '[unite] the technical and imaginative elements as essentially as humanity does soul and body'.5

Ruskin's radical contribution was therefore to posit a unitary view of art and society — like the vision of Bellini's Procession in Piazza San Marco — which initially seemed strange to the industrialising Victorians. In seeking the 'large principles of right'6 of architecture through its related social questions, Ruskin recognised that 'architecture is built upon labour'.7 So, the first volume of The Stones of Venice thrusts a trowel in its readers' hands, urging them to imaginatively engage with the writer in the physical act of building from base to cornice, and by these means to share Ruskin's admiration for 'the grand power and heart of man in the thing'.8

Thus — in analysing the organic ornament of a Byzantine archivolt at the Corte del Remer at Venice's Rialto — Ruskin declares that 'the commandment is written on the heart of the thing'.9 Giovanni Leoni stresses this sense of 'thingness': for Ruskin, he argues, 'the Law is in the stones, or substance; it is architecture as a concrete fact, a thing created by the work of [humanity]'. Accordingly 'architecture cannot be entirely reduced to representation; for it has a substance, concreteness and life independent of representational form'.10 In seeking the 'heart of the thing', Ruskin is drawn centripetally closer to the architectural surface in a synthesis of visual, haptic and even oral engagement — that of the Verona he sought 'stone by stone, to eat... all up into [his mind), touch by touch'.11

Ruskin dates the start of the 'course of architectural study which reduced under accurate law the vague enthusiasm of my childish taste'12 to Lucca, between the 3 and 12 May 1845. At Lucca — in churches like San Michele — he 'absolutely for the first time ... saw what medieval builders were, and what they meant ... And thereon literally began the study of architecture'.13 In the new 'method' of study, the closely watched fragment becomes emblematic of the whole. As the vigilant watcher Ruskin responded acutely to San Michele's decay: 'Pity that the sea wind blowing through the apertures has so eaten away the marble that in parts it crumbles to the hand like a lump of salt.'14 Yet weathering, for Ruskin, is also part of 'the writing upon the pages of ancient walls of the confused hieroglyphics of human history'.15 Perfect though Gentile Bellini's representation of architecture is in most aspects, it stands accused in Modern Painters of lacking 'solidity, depth or gloom' or the 'signs of age and the effects of use and habitation'.16

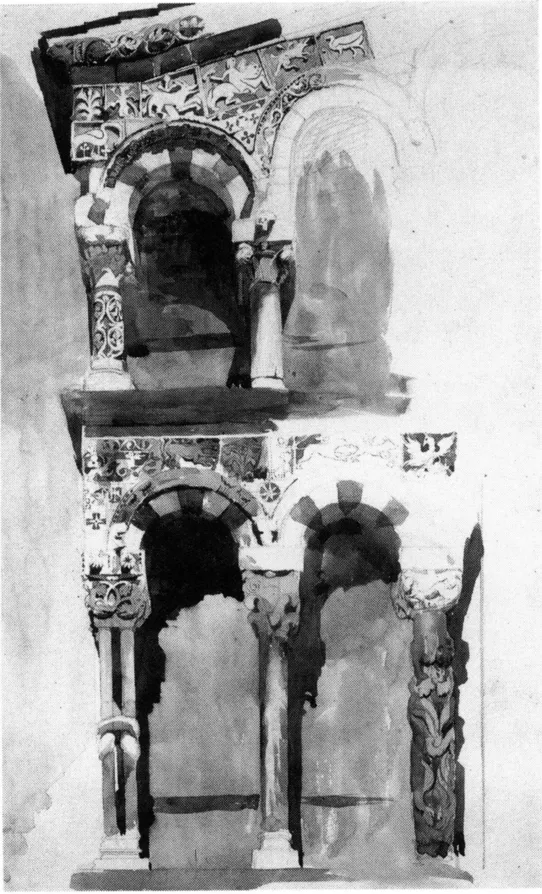

In this light, it is instructive to compare the 1845 study of San Michele with the more forceful attempt made on a return to Lucca in the period 30 June—1 July 1846. The first 1845 study of the facade is delicate and linear; strong shadows are suppressed in Ruskin's concern to minutely record every interlacing leaf of the cornice. There is a Bellini-esque sweetness here, but is this the full 'heart of the thing' that must also embody gloom and the marks of time? Moving to the other end of the facade in 1846, and gazing yet closer, Ruskin brings out the chiaroscuro of the subject in strongly applied washes (see figure opposite). He renders the entire cornice below the upper arcade in broad strokes of dark umber, and forcibly lays in the shadows despite the loss of detail. Cropped more tightly still, to a single arch, the motif becomes the gritty etching — Plate VI, of The Seven Lamps of Architecture — showing how the 'wall surface ... could only be made valuable by points or masses of energetic shadow'; shadow thus becomes reciprocal to light as a positive figure. Pointing to Edmund Burke's contention that 'darkness is more productive of sublime ideas than light', Kent Bloomer argues that

Part of the facade of San Michele, Lucca, 1846. Watercolour and pencil.

in Ruskin 'shadow takes on an independent ... multiplicity of meanings'.17 Indeed Ruskin is capable of reading the 'antagonism of the entire human system' — the play of good and evil, life and death — in the smallest of details, such as the 'chains of shade and light' that characterise the Venetian billet moulding.18

Touchstones of right and wrong

Equally, following the San Michele arch — in Plate VIII of The Seven Lamps of Architecture — Ruskin's detail of the Palazzo Foscari window at Venice shows a magnificent example of the 'forms of the shadows', and the 'masses of light and darkness'.19 At this great fifteenth-century palace on the Grand Canal, Ruskin expands the 'method' initiated at Lucca in ways which foreshadow the system of scrutiny applied a fortiori in the 1849-50 winter fieldwork for The Stones of Venice. This had not been in his plans: 'I purpose [sic] drawing little architecture, if any, at Venice ...' he had told his father in a letter of 7 September from Verona.20 But on arrival in the city Ruskin was traumatised by the ammiglioramenti (improvements) of a city anxious to innovate. Most prominent of these signs of modernity was the near completion (1846) of the rail bridge to the mainland which cut 'off the whole open sea & half the city, which now looks as nearly as possible like Liverpool at the end of the dockyard wall'21 'As matters stand', he wrote to his father in torment, the intended 'picture work' for Modern Painters had to take second place, the architecture, 'the out of door is the most important'.22

Given the extent to which the Venetian architectural studies were to grow, they emerge tentatively from 1845 notebooks mostly filled with observations on painting and sculpture. Ruskin begins with the Palazzo Foscari — why? As often with him, he is drawn to a building by an indissoluble combination of literary, moral, aesthetic and analytical impulses. Byron 'bade me seek first in Venice — the ruined homes of Foscari and Falier', he recalls in the autobiographical Praeterita.23 Ruskin, in fact, both inherits the remote poetic city of Byron and Shelley, and foreshadows the city's initiation into the modern world of Henry James, Proust, conservation and mass leisure travel.24 Thus he paraphrases from Byron's tragic play The Two Foscari — concerning the deposition of Doge Francesco Foscari (1423-57) — when he states his ambition in the opening pages to make 'the Stones of Venice touchstones ... detecting, by the mouldering of her marble, poison more subtle than ever was betrayed by the rending of her crystal'25 — namely touchstones to distinguish 'a criterion of right and wrong in so practical and costly an art as architecture'.26

In faint pencil, the notebook contains the following pathetic account of nearing the building:

Venice 13th Sept

The Pal. Foscari seen far off still looks stable — as one approaches the rents & the ruin show themselves — like the signs of death on a corpse which one approaches thinking asleep.27

Three pages on, Ruskin enters the ruined androne (entrance hall) of the palace and produces a study looking towards the water-gate in his most atmospheric pen-and-wash manner (see figure opposite (top)). But of much more interest in terms of the evolution of Ruskin's 'method' of 'accurate law' than this example of his picturesque visualisation are the facade studies of the palace facing page 17 (see figure opposite (bottom)).28 Again, observe in these pages how the evolving analytical methodology arises within the approaches of a traditional picturesque sketching tour. En-route to Venice, Ruskin had been joined by the artist J.D. Harding, and from early in the morning they would moor among the boats in the fruit market; thus there are a number of pages of finely detailed studies of figures and boats, dated 11 September.29 Boat and figure esquisses even invade the centre of the Foscari page of studies where Ruskin's gaze is drawn to the great eight-bay window of the second floor of the palace. It is of a tracery type which captivated him ('the 4 foil circle between ogee curves')30 for its intrinsic majesty, and its descent from the arcades of the Doge's Palace — the 'central building of the world' in The Stones of Venice owing to its equal fusion, in Ruskin's view, of Roman, Lombard and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Illustration credits

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Politics of Cities

- Politics of Makers

- Politics of Seeing

- Index