eBook - ePub

Remaking Birmingham

The Visual Culture of Urban Regeneration

Liam Kennedy, Liam Kennedy

This is a test

Share book

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Remaking Birmingham

The Visual Culture of Urban Regeneration

Liam Kennedy, Liam Kennedy

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The city of Birmingham offers a particularly rich case study on urban regeneration as it strives to build a new city image. Positioned between decline and regeneration, the landscape of the city and its environs collages old and new, producing dramatic contrasts - of industrial and post-industrial urbanisms of crumbling brutalism and spectacular flagship developments, of Victorian housing and diverse cultural lifestyles - that compound the aesthetic and socio-economic means of regeneration. This visually exciting book also reflects upon and extends current debates about public space, cultural zoning and the futures of cities.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Remaking Birmingham an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Remaking Birmingham by Liam Kennedy, Liam Kennedy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Concrete Dreams

Chapter 1

Street, Subway and Mall

Spatial Politics in the Bull Ring

The production, management and occupation of public urban space are political activities of the utmost importance to citizens. One wishes that to write this opening sentence were a platitudinous statement of the obvious, but sadly this is not the case. Too often, public urban space, if it is thought about at all, is thought of as neutral territory; merely the space left over between the buildings. Buildings—what urban designers call collectively the city's urban fabric—obviously contribute greatly to the forming of the city's character, its identity, its spirit. But while they may be beautiful or ugly or just ordinary, buildings possess little in the way of a political dimension, because little of the public life of the city takes place within them. Public life predominantly takes place outside, in the street and the square, in the public realm; Life Between Buildings, as a respected book on the subject describes it (Gehl 1996).

This inhabitation of public space is political, because it raises issues of ownership, of control, of complexity, of conflicts of use, of limits on freedom of activity, which affect the well-being of the individual and the community, and on which decisions have somehow to be made, whether consensually or not. These issues are generally not present in the interior of even the most public building. If I go to a concert in Symphony Hall in Birmingham, I am content that the programme is decided by someone else, that the start and finish times are fixed, and that between those times I occupy the seat allocated to me. But if upon leaving Symphony Hall, I find that what appeared yesterday to be a public square is now fenced off, and dedicated to a private commercial activity, say the launch of the new model of Rover car, then I experience a dispossession. Clearly, I was mistaken in thinking that, as a citizen, I had some right of occupation over this apparently public space, some freedom of choice and action.

This sense of diminishment of the public realm is a commonplace nowadays. It is typically caused by a political process whereby public space is metamorphosed into private space, or at best, quasi-public space. Centenary Square is a quasi-public space; it looks like a public square, but it is not. It is a City Council-owned private space that the public is allowed to use when it is not being used for something else. The privatization of public space is mostly associated with large urban retail redevelopments. Here we typically see

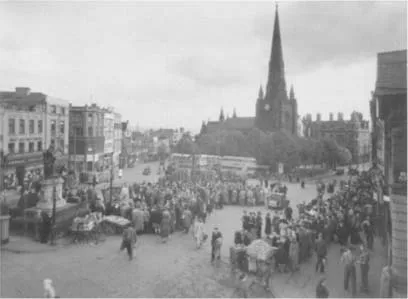

1.1 The Bull Ring in 1952

the traditional, all-purpose public street being replaced by something more narrowly tailored to a single purpose which suits the developer's interests; a 'retail environment'. The saga of the arguments over the redevelopment of the Bull Ring is the most prominent case in Birmingham where the political nature of public space has been made explicit, and become the focus of public debate.1

The Bull Ring is where the markets of Birmingham have been situated since a royal charter allowing a market was granted in 1166 to what was then a small village. In most towns the market square, which in Birmingham followed a typical English pattern of the widening out of the High Street into a triangular space, closed by the parish church at the far end, has usually been the central public space. This reflects the dominant role of mercantile exchange in its life and culture. In Birmingham the open air market of the Bull Ring drew around itself a supportive network of other traders, inns and businesses, and eventually the town's first major nineteenth-century public building, the Market Hall. But during the nineteenth century the centre of the town migrated westwards, and the Bull Ring was no longer the central public space. A more bourgeois, cultural and administrative centre grew around the new focal spaces of Victoria Square and Chamberlain Place. This emphasized by contrast the role of the Bull Ring as the city's working-class locus. Today, with the growth of other shopping alternatives for the more affluent and mobile, the markets are economically important for the elderly and for poorer working-class families in particular.

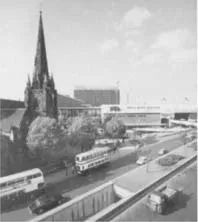

1.2 The Bull Ring in 1970

Until 1959, the Bull Ring (shown in Figure 1.1) was a popular, democratic, public space. It was not particularly attractive, but it was a vigorous, lively, sensually rich public realm; vulgar in the best sense of the word. Market traders and shops were joined by salesmen, hawkers, the noted escapologist and other performers. It was a public arena that was open to possibilities, a theatre of spontaneous popular culture. Topographically the Bull Ring was made memorable by its gradient; the space fell about 15 metres from New Street down to the parish church, rendering it even more theatrical.

Then modernist replanning arrived with the simultaneous building of the Inner Ring Road (the Queensway) and the Bull Ring Centre, Britain's first city-centre indoor shopping mall. Together, these two developments destroyed the coherence of the urban space of the Bull Ring. Remarkably the outdoor market stayed more or less where it previously had been. But instead of occupying a legible urban square, connected to adjacent places by conventional streets, the market (shown in Figure 1.2) was hemmed in between and underneath highways, reached only by unpleasant and disorientating subways and passages. The Bull Ring Centre itself, built by Laing Developments, was a disastrous failure in both design and economic terms.2

The redevelopment of the Bull Ring by Hammerson, which will be completed in 2003, will create the third environment in this place during my lifetime and those of my contemporaries. It began with the purchase in the mid-1980s of the remainder of Laing's lease by the developers London and Edinburgh Trust (LET), which was followed by years of public argument over the correct form for a new development. It was an opportunity to identify the fundamental mistakes made in the development of the 1963 Bull Ring Centre, under the influence of misguided modernist doctrine, and to revert to what by that time was established as an orthodox postmodern urban design strategy.

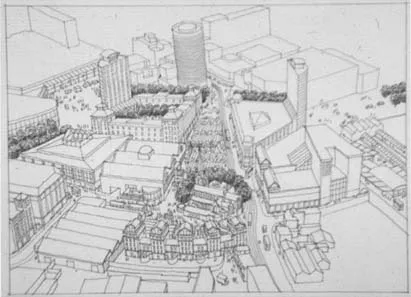

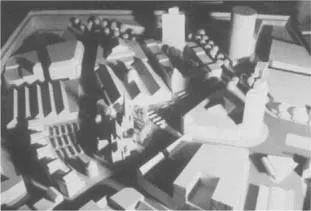

1.3 The People's Plan for the Bull Ring, 1989. Plan showing blocks and streets

This strategy was proposed by the campaigning group Birmingham for People, of which the author was a member during its existence from 1988 to 1998, in its 1989 alternative development proposal called The People's Plan for the Bull Ring (Birmingham for People 1989) which can be seen in Figure 1.3–1.6. Its constituent elements can be summarized asfollows: a mixture of land uses, the shaping of a traditional marketplace enclosed by buildings, medium-sized blocks of buildings, conventional outdoor streets, and all pedestrian and vehicular movement at ground level. These elements were all traditional, not to say old-fashioned, which meant that in the context of 1989 The People's Plan was surprisingly radical.

These urban elements are in opposition to what retail developers generally want to build. The purest form of the developers' retail model can be seen in out-of-town developments such as Meadowhall near Sheffield, or Bluewater in Kent. Here, instead of mixed uses, there is retail use only, with perhaps some ‘leisure’ uses added to enrich the shopping experience. Instead of a fine grain of urban blocks such as we find in a conventional city centre, there is gargantuan scale; what in architectural terms we might call the megastructural approach. Instead of outdoor streets and squares, there are indoor malls. And of course, and most critically, these indoor malls are not public spaces; they are privately owned space, and they have doors that close at the end of shopping hours.

The choice of the private, indoor mall as the preferred form for new retail development represents a fear, or at least distrust, of the street. The public space of the street is an arena for the unpredictable. Not only might rain fall on your head, but you might encounter strange people, poor people, ugly people, there for a variety of different purposes, exhibiting a variety of different kinds of behaviour. All over that part of the world where the traditional street was degraded in the mid-twentieth century by the dominance of modernism, the social and sensory stimulation of the public street is being rediscovered and celebrated. This is truer in Birmingham than in most places. Contemporary with the development of the 1963 Bull Ring Centre, streets all over the city centre and

1.4 The People's Plan for the Bull Ring, 1989. Perspective view of the new marketplace looking towards St Martin's

beyond were reduced to mere utilitarian corridors for vehicles, with pedestrians consigned to subways. The renaissance of public space in Birmingham in recent years—the pedestrianization of New Street, the redesign of Victoria Square, the creation of Centenary Square and Brindleyplace Square—has been a great popular success, and has been recognized by several official awards.

In these places, the true nature and purpose of the street as a sociable space, which has been true everywhere for millennia, are once again acknowledged. Among the wide range of examples of humankind that may be encountered there may be some which are strange, or unpleasant, or even threatening. Yet the fundamental principle that Jane Jacobs documented as long ago as 1961 is still self-evidently true: a well-used and well-populated street is a safe street, as well as a stimulating street (Jacobs 1961). In Birmingham we may now see citizens strolling the streets and squares purely for pleasure, in a version of the Italian passeggiata—something unheard of 20 years ago.3

The nineteenth-century shopping arcade, such as Great Western Arcade or City Arcade in Birmingham, was an addition to the network of traditional streets. They were typically cut through existing urban blocks to create additional retail frontage, getting more out of a given area. They were indeed usually private spaces, and were gated after shop opening hours. But their closure at night did not reduce the utility of the street network; they augmented it when they were open.

The threat of the modern urban retail development, by contrast, is that, through distrust or fear of the street, it seeks to replace the public street with the private mall. The initial 1987 design for the redevelopment of the Bull Ring, by the architects Chapman Taylor for LET (shown in Figure 1.7), proposed a giant box

1.5 The People's Plan for the Bull Ring, 1989. Aerial perspective, looking towards the city centre

1.6 The People's Plan for the Bull Ring, 1989. Model of the proposed development

containing three levels of indoor mall, 500 metres in length. This was what The People's Plan set out to counter. Entirely intro verted, it had no positive connection with streets, and would have been extremely disruptive to the existing street network (already damaged by the 1960s' redevelopment and roadbuilding). In 1988, its architect described the proposal as 'a huge

1.7 Mall-level plan of the original LET proposal for The Galleries, 1987

aircraft-carrier settled on the streetscape of the city'.4 He presumably thought this an admirable vision—others were understandably horrified by the prospect.

Over the past 50 years, we have seen three different mod...