![]()

Part I

Conceptualizing and Measuring Performance

![]()

CHAPTER

1

JOB ANALYSIS FOR THE FUTURE

Michael A. Campion

Purdue University

This chapter is based on two premises. First, our science has knowledge about how jobs are designed that is relevant to developing selection and classification systems, but is not currently measured in most job analysis studies. Future research should explore the value of including job design measures in job analysis studies.

Second, most current job analysis studies do not specifically consider requirements for teamwork, and thus do not provide a basis for reflecting those requirements in subsequent selection and classification systems. Future research should explore the value of examining teamwork more explicitly in job analysis studies.

This chapter draws on recent research on job and teamwork design conducted by the author and his colleagues in order to derive propositions for changes in future job analysis studies conducted to develop selection and classification systems.

ANALYZING JOB DESIGN

The theoretical background for the author’s research on job design comes from a variety of different academic disciplines. This interdisciplinary perspective is briefly described first. Then propositions for job analysis research are derived and discussed. Finally, measurement is addressed, including instrumentation and sources of information used in past studies.

Interdisciplinary Framework

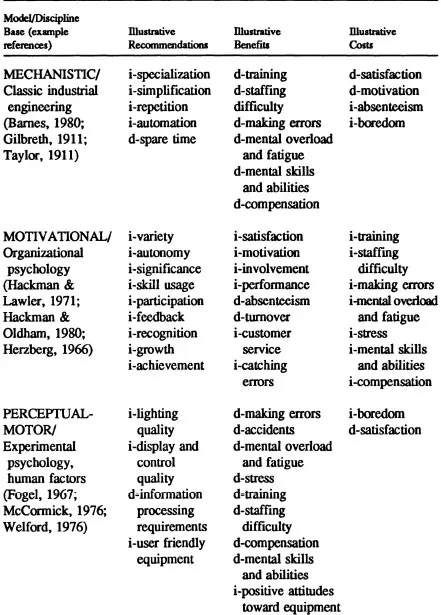

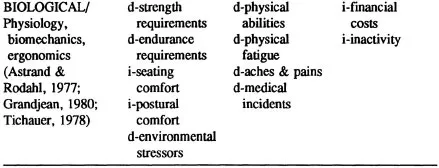

The author’s research has attempted to consider a variety of models of job design. Each of these models is derived from a different academic discipline, and each has a different set of intended outcomes. Four models are fairly inclusive of the major schools of thought, even though they may not be exhaustive. The four models and their outcomes are briefly described here, summarized in Table 1.1, and documented in previous articles (Campion, 1985, 1988, 1989; Campion & Berger, 1990; Campion, Kosiak, & Langford, 1988; Campion & McClelland, 1991, 1993; Campion & Medsker, 1992; Campion & Stevens, 1991; Campion & Thayer, 1985, 1987, 1989; Campion & Wong, 1991; Wong & Campion, 1991).

First, a mechanistic model comes from classic industrial engineering. It provides recommendations based on scientific management, time and motion study, and work simplification (Barnes, 1980; Gilbreth, 1911; Neibel, 1992; Taylor, 1911). It is oriented toward human resource efficiency and flexibility outcomes such as staffing ease, low training requirements, reduced mental skills, and low compensation requirements.

Second, a motivational model comes from organizational psychology. It provides recommendations based on job enrichment and enlargement (Herzberg, 1966), characteristics of motivating jobs (Hackman & Lawler, 1971; Hackman & Oldham, 1980), theories of work motivation (Mitchell, 1976; Steers & Mowday, 1977), and psychological principles from sociotechnical approaches (Cherns, 1976; Englestad, 1979; Rousseau, 1977). It represents an encompassing collection of recommendations intended to enhance the motivational nature of jobs, and it has been associated with affective outcomes such as satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and involvement, as well as behavioral outcomes such as performance, customer service, and low turnover.

Third, a perceptual-motor model comes from experimental psychology. It provides recommendations based on human factors engineering (McCormick, 1976; Van Cott & Kinkade, 1972), skilled performance (Welford, 1976), and human information processing (Fogel, 1967; Gagne, 1962). It is oriented toward reducing demands on human mental capabilities and limitations, primarily with regard to lowering attention and concentration requirements of jobs. It has been shown to be related to reliability outcomes (e.g., reduced errors and accidents) and positive user reactions (e.g., reduced mental overload, fatigue, and stress, and favorable attitudes toward the workstation and equipment).

Fourth, a biological model comes from work physiology (Astrand & Rodahl, 1977), biomechanics (Tichauer, 1978), and ergonomics (Grandjean, 1980). This model attempts to minimize physical stress and strain on the worker, and it has been associated with less physical effort and fatigue, more comfort, and fewer aches, pains, and health complaints.

Although there are some similarities in the recommendations made for proper job design by the different disciplines, there are also considerable differences and even some direct conflicts. Such differences mean that each model has costs as well as benefits. The costs are the lost benefits of the other models. The most central conflict is between the mechanistic and perceptual-motor models on the one hand, which both generally recommend design features that minimize mental demands, and the motivational model on the other hand, which gives the opposite advice by recommending design features that enhance mental demands. Therefore, the motivational model may create costs in terms of staffing difficulty, increased training requirements, greater likelihood of errors, more overload, more stress, and increased compensation requirements. The mechanistic and perceptual-motor models may create costs in terms of less satisfaction and motivation, greater boredom, and higher turnover. The biological model is fairly independent because it reflects physical demands, but it may also have costs in terms of financial requirements for changing equipment and environments, as well as the potential for inadequate physical activity.

TABLE 1.1

Interdisciplinary Models of Job Design

Note. Benefits and costs based on findings in previous interdisciplinary research (Campion, 1988, 1989; Campion & Berger, 1990; Campion & McClelland, 1991, 1993; Campion & Thayer, 1985). Table adapted from Campion and Medsker (1992). Key: i = increased, d = decreased.

Propositions for Job Analysis

Proposition 1. Including measures of job design in future job analysis studies may help identify potential costs (negative outcomes) from the job that could subsequently be used as criteria for the selection system. For example, jobs poorly designed on the perceptual-motor model would be expected to have potential costs in terms of errors, mental overload, accidents, and stress. Minimizing these outcomes could then become the focus of future selection systems. Not only could they become the criteria for empirical validation studies, but they might suggest the abilities or attributes on which to focus the predictors (e.g., information-handling capacity, quality orientation, safety awareness, stress tolerance).

Likewise, for jobs high on the mechanistic or perceptual-motor models, there could be costs in terms of reduced satisfaction and motivation and increased boredom. When jobs are designed in such a manner that these costs are likely, the selection systems could be oriented to help counteract them. Affective outcomes like satisfaction are usually ignored as validation criteria, despite their relationships with a host of important behavioral outcomes (e.g., turnover, unionism). Again, in this way selection systems can compensate for poorly designed jobs. Jobs well designed on the motivational model, which is the only model taught in most business and management schools (see typical human resources textbooks such as Heneman, Schwab, Fossum, & Dyer, 1989; or Milkovich & Boudreau, 1991), are likely to have higher mental ability requirements, greater training needs, and some of the same costs associated with the poor perceptual-motor design already described (e.g., errors and overload). This may suggest that a selection system based on cognitive abilities is needed, and it may also suggest modifications to existing systems such as raising cutting scores and using training criteria for validation. Finally, jobs poorly designed on the biological model may have costs in terms of physical demands and requirements. Physically demanding jobs have special implications for selection system development and validation that are not well understood by most behavioral scientists (Campion, 1983).

Proposition 2. Individual differences identified in job design research may be worth exploring as experimental predictors and should, thus, be considered in future job analysis studies. Research within the motivational model of job design has identified higher-order needs as potential moderators of employee reactions to enriched jobs (Hackman & Lawler, 1971). Those with more higher-order needs respond more positively to enriched work. Research within the interdisciplinary perspective on job design has expanded this notion into preferences or tolerances for all four job design models. Thus, employees may differ with respect to their preferences or tolerances for motivational work (e.g., challenging, mentally demanding, working without supervision), mechanistic work (e.g., routine, repetitive), perceptual-motor work (e.g., fast-paced, complicated, stressful), and biological work (e.g., physically demanding, environmental stressors). There is evidence that these individual differences moderate reactions to the various models of job design to some degree (Campion, 1988; Campion & McClelland, 1991, 1993).

These individual differences have not been examined in previous selection research to the author’s knowledge, but may offer a fruitful avenue to explore. They are personality oriented and, thus, might be difficult to use in a selection context due to susceptibility to faking. However, a variety of approaches could be explored to overcome this potential problem (e.g., disguise question purpose, control for social desirability, use biodata measures).

Proposition 3. Anticipated changes in jobs, as well as jobs not yet developed, can be analyzed in terms of job design, and such information can have implications for the development or modification of selection systems. As noted above and in Table 1.1, staffing ease or difficulty is an outcome of job design that has been identified in previous research. This outcome derives from the industrial engineering concept of “utilization level,” defined as the proportion of employees who can perform the job. In traditional industrial engineering, the goal is to design jobs that can be performed by all potential employees who might be assigned to them.

In personnel selection vernacular, jobs with high utilization levels usually have low mental ability requirements; they can be easily staffed because of the wide range of competence that can be accommodated. Therefore, changes in jobs that increase staffing difficulty suggest a corresponding increase in the need for a selection system based on mental abilities or a need for a modification of the current system (e.g., raising the cutting score or expanding the applicant pool). Job design measures are especially useful for forecasting these changes in selection systems because they require less information to use than do the traditional job analysis systems, which require specific information on tasks and skills. These measurement issues will be addressed later in the chapter.

Proposition 4. Interdependence among tasks on the same job has been shown to predict ability requirements in job design research and, thus, should potentially be examined in future job analysis studies. Task interdependence is the degree to which the inputs, processes, or outputs of some tasks in a given job depend on the inputs, processes, or outputs of other tasks in the job. Research has shown that interdependence among tasks is related to the motivational value of a job and to the job’s ability requirements (Wong & Campion, 1991). Interdependence among tasks has a unique effect on ability requirements beyond the effects of job design. The importance of task-level analysis in order to understand ability requirements has long been reported in job analysis research, but this study would suggest that interdependencies among the tasks are also important to consider in order to more fully understand ability requirements, and should be included in future job analysis studies.

Proposition 5. Changing the job should be considered as an alternative to changing the selection and placement systems. The implicit assumption that jobs are fixed and technologically determined and, thus, human resource systems must be adapted to them, is incorrect. Jobs are inventions (Davis & Taylor, 1979). Typically, they reflect the values of the era in which they were constructed (e.g., mechanistic design earlier in the century, motivational design after that, and team design most recently). Jobs are not immutable givens but are subject to change and modification. Thus, they can be changed to increase the need for selection systems (e.g., typically by applying the motivational model), or jobs can be designed to decrease the need for selection systems (e.g., typically by applying the mechanistic and perceptual-motor models). If it is too difficult to find an adequate number of employees with the needed abilities, perhaps changing the jobs to reduce their ability requirements should be considered.

Measurement of Job Design

Several instruments have been developed to measure the four interdisciplinary models of job design. The original study (Campion & Thayer, 1985) used an analysis instrument that was completed based on observation (contained in Campion, 1985). It was very detailed in terms of including explanations of each of the job design recommendations, but it was somewhat oriented toward blue-collar jobs. Subsequent research developed a self-report version (contained in Campion, 1988; Campion & Medsker, 1992) because many jobs and situations preclude the use of observational measures. The self-report version can also be used on the entire range of blue- and white-collar jobs.

More recent research has further modified the self-report instrument to make it easier to complete (e.g., changed items to first person, adopted singular format similar to the survey format familiar to employees, simplified several questions). That instrument is described in Campion and McClelland (1991, 1993) and is available from the author. The self-report version of the instrument has been used with analysts and supervisors, as well as incumbents.

All three versions of the instrument have demonstrated adequate psychometric qualities, including internal consistency; interrater reliability and agreement among and between incumbents, managers, and analysts; and convergent and discriminant validity with other popular measures of job design (Campion, Kosiak, & Langford, 1988). All three versions have also demonstrated substantial relationships with the wide range of costs and benefits described above, both in cross-sectional research (that avoids common methods variance, such as Campion, 1988; Campion & Thayer, 1985) and quasi-experimental research (Campion & McClelland, 1991, 1993).

Two other instruments have been developed that might have value in future job analysis studies. First, a measure of the preferences for and tolerances of different types of work is contained in Campion and Medsker (1992), and evidence of the moderating effect of these individual differences is contained in Campion (1988) and Campion and McClelland (1991, 1993). Second, a measure of interdependencies among tasks is contained along with evidence of its validity in Wong and Campion (1991).

In summary, measures of job design are easy to use and would logically fit in a job analysis questionnaire. They provide information on the nature of the jobs that is different from that obtained by traditional job analysis measures. They can identify likely costs and benefits of jobs without having to measure the outcomes directly. This is especially useful for developing selection systems for jobs that do not yet exist.

Also, job design measures may be somewhat easier to complete than normal job analysis questionnaires when the jobs do not yet exist or when potential changes in jobs are being evaluated. This is because they do not require knowledge of specific details about tasks and skills, but instead require only an assessment of the...