- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cognitive Skills and Their Acquisition

About this book

First published in 1981. This book is a collection of the papers presented at the Sixteenth Annual Carnegie Symposium on Cognition, held in May 1980.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Mechanisms of Skill Acquisition and the Law of Practice

Introduction1

Practice makes perfect. Correcting the overstatement of a maxim: Almost always, practice brings improvement, and more practice brings more improvement. We all expect improvement with practice to be ubiquitous, though obviously limits exist both in scope and extent. Take only the experimental laboratory: We do not expect people to perform an experimental task correctly without at least some practice; and we design all our psychology experiments with one eye to the confounding influence of practice effects.

Practice used to be a basic topic. For instance, the first edition of Woodworm (1938) has a chapter entitled “Practice and Skill.” But, as Woodworm [p. 156] says, ‘There is no essential difference between practice and learning except that the practice experiment takes longer.” Thus, practice has not remained a topic by itself but has become simply a variant term for talking about learning skills through the repetition of their performance.

With the ascendence of verbal learning as the paradigm case of learning, and its transformation into the acquisition of knowledge in long-term memory, the study of skills took up a less central position in the basic study of human behavior. It did not remain entirely absent, of course. A good exemplar of its continued presence can be seen in the work of Neisser, taking first the results in the mid-sixties on detecting the presence of ten targets as quickly as one in a visual display (Neisser, Novick, & Lazar, 1963), which requires extensive practice to occur; and then the recent work (Spelke, Hirst, & Neisser, 1976) showing that reading aloud and shadowing prose could be accomplished simultaneously, again after much practice. In these studies, practice plays an essential but supporting role; center stage is held by issues of preattentive processes, in the earlier work, and the possibility of doing multiple complex tasks simultaneously, in the latter.

Recently, especially with the articles by Shiffrin & Schneider (1977; Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977), but starting earlier (LaBerge, 1974; Posner & Snyder, 1975), emphasis on automatic processing has grown substantially from its level in the sixties. It now promises to take a prominent place in cognitive psychology. The development of automatic processing seems always to be tied to extended practice and so the notions of skill and practice are again becoming central.

There exists a ubiquitous quantitative law of practice: It appears to follow a power law; that is, plotting the logarithm of the time to perform a task against the logarithm of the trial number always yields a straight line, more or less. We shall refer to this law variously as the log-log linear learning law or the power law of practice.

This empirical law has been known for a long time; it apparently showed up first in Snoddy’s (1926) study of mirror-tracing of visual mazes (see also Fitts, 1964), though it has been rediscovered independently on occasion (DeJong, 1957). Its ubiquity is widely recognized; for instance, it occupies a major position in books on human performance (Fitts & Posner, 1967; Welford, 1968). Despite this, it has captured little attention, especially theoretical attention, in basic cognitive or experimental psychology, though it is sometimes used as the form for displaying data (Kolers, 1975; Reisberg, Baron, & Kemler, 1980). Only a single model, that of Crossman (1959), appears to have been put forward to explain it.2 It is hardly mentioned as an interesting or important regularity in any of the modern cognitive psychology texts (Calfee, 1975; Crowder, 1976; Kintsch, 1977; Lindsay & Norman, 1977). Likewise, it is not a part of the long history of work on the learning curve (Guilliksen, 1934; Restle & Greeno, 1970; Thurstone, 1919), which considers only exponential, hyperbolic, and logistic functions. Indeed, a recent extensive paper on the learning curve (Mazur & Hastie, 1978) simply dismisses the log-log form as unworthy of consideration and clearly dominated by the other forms.

The aim of this chapter is to investigate this law. How widespread is its occurrence? What could it signify? What theories might explain it? Our motivation for this investigation is threefold. First, an interest in applying modern cognitive psychology to user-computer interaction (Card, Moran, & Newell, 1980a; Robertson, McCracken, & Newell, in press) led us to the literature on human performance, where this law was prominently displayed. Its general quantitative form marked it as interesting, an interest only heightened by the apparent general neglect of the law in modern cognitive psychology. Second, a theoretical interest in the nature of the architecture for human cognition (Newell, 1980) has led us to search for experimental facts that might yield some useful constraints. A general regularity such as the log-log law might say something interesting about the basic mechanisms of turning knowledge into action. Third, an incomplete manuscript by Clayton Lewis (no date) took up this same problem; this served to convince us that an attack on the problem would be useful. Thus, we welcomed the excuse of this conference to take a deeper look at this law and what might lay behind it.

In the next section we provide many examples of the log-log law and characterize its universality. In the following section we perform some basic finger exercises about the nature of power laws. Then we investigate questions of curve fitting. In the next section we address the possible types of explanations for the law; and we develop one approach, which we call the chunking theory of learning. In the final section, we sum up our results.

The Ubiquitous Law of Practice

We have two objectives for this section. First, we simply wish to show enough examples of the regularity to lend conviction of its empirical reality. Second, the law is generally viewed as associated with skill, in particular, with perceptual-motor skills. We wish to replace this with a view that the law holds for practice learning of all kinds. In this section we present data. We leave to the next section issues about alternative ways to describe the regularity and to yet subsequent sections ways to explain the regularity.

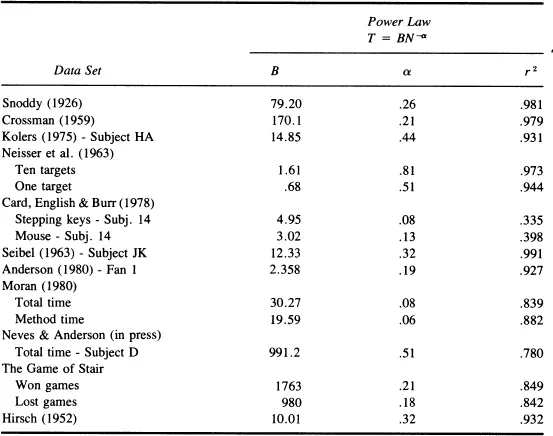

We organize the presentation of the data by the subsystem that seems to be engaged in the task. In Table 1.1 we tabulate several parameters of each of the curves. Their definitions are given at the points in the chapter where the parameters are first used.

Perceptual-Motor Skills

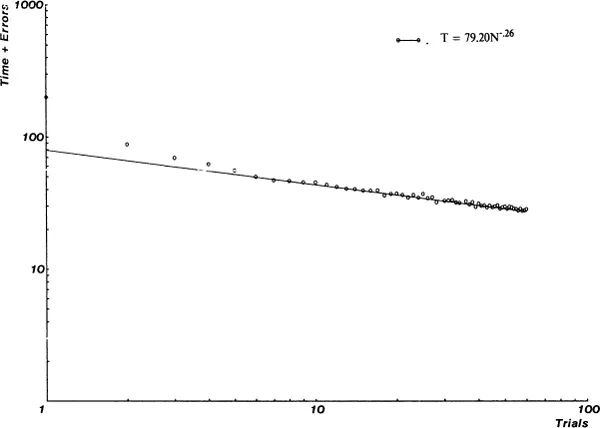

Let us start with the historical case of Snoddy (1926). As remarked earlier, the task was mirror-tracing, a skill that involves intimate and continuous coordination of the motor and perceptual systems. Figure 1.1 plots the log of performance on the vertical axis against the log of the trial number for a single subject.

Table 1.1

Power Law Parameters for the (Log-Log) Linear Data Segments

Power Law Parameters for the (Log-Log) Linear Data Segments

The first important point is:

• The law holds for performance measured as the time to achieve a fixed task.

Analyses of learning and practice are free a priori to use any index of performance (e.g., errors or performance time, which decrease with practice; or amount or quality attained, which increase with practice). However, we focus exclusively on measures of performance time, with quality measures (errors, amount, judged quality) taken to be essentially constant. Given that humans can often engage in tradeoffs between speed and accuracy, speed curves are not definable without a specification of accuracy, implicit or otherwise.3 As we illustrate later, the log-log law also appears to hold for learning curves defined on other performance criteria. Though significant for understanding the cause of the power law, we only note the existence of these other curves.

F...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Mechanisms of Skill Acquisition and the Law of Practice

- 2. Knowledge Compilation: Mechanisms for the Automatization of Cognitive Skills

- 3. Skill In Algebra

- 4. The Development of Automatism

- 5. Skilled Memory

- 6. Acquisition of Problem-Solving Skill

- 7. Advice Taking and Knowledge Refinement: An Iterative View of Skill Acquisition

- 8. The Processes Involved in Designing Software

- 9. Mental Models of Physical Mechanisms and Their Acquisition

- 10. Enriching Formal Knowledge: A Model for Learning to Solve Textbook Physics Problems

- 11. Analogical Processes in Learning

- 12. The Central Role of Learning in Cognition

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Cognitive Skills and Their Acquisition by John R. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.