- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1982. This book summarizes certain concepts and evidence regarding the nature of close personal relationships. Its purpose is to suggest how such relationships are to be conceptualized for scientific analysis. What are the essential properties of a personal relationship? What are its necessary defining structures and processes? The material presented herein represents what Kelley has thought and learned about the social psychology of close relationships.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction | 1 |

This book summarizes certain concepts and evidence regarding the nature of close personal relationships. Its purpose is to suggest how such relationships are to be conceptualized for scientific analysis. What are the essential properties of a personal relationship? What are its necessary defining structures and processes?

In everyday usage, we use the term close personal relationship to refer to lovers, marriage partners, best friends, and persons who work closely together. An everyday description of this kind of relationship will refer to its long-lasting nature; the fact that the persons spend much time together, do many things together, and (often) share living or working quarters; the intercommunication of personal information and feelings; and the likelihood that the persons see themselves as a unit and are seen that way by others.

In this book I attempt to formulate a scientific description to take the place of this everyday one. The purpose is to gain an understanding of such relationships that will make possible their systematic assessment and classification and provide a basis for interventions to improve their functioning. The underlying assumptions are that close interpersonal relations constitute distinctive and important social phenomena and that a systematic coherent conceptualization of them is necessary in order to develop, appreciate, and modify them.

The focus is on the close heterosexual dyad—the intimate relationship between man and woman. I believe (but do not attempt to demonstrate) that my concepts are applicable to any relationship we would regard as a personal one. The choice of the heterosexual dyad as the subject of analysis is dictated partly by the fact that it is the basis of most of the current knowledge about personal relationships. Additionally, in its various manifestations in dating, marriage, cohabitation, and romantic liaisons, the heterosexual dyad is probably the single most important type of personal relationship in the life of the individual and in the history of society. It occasions the greatest satisfactions of life and also the greatest disappointments. As the core of the family group, the heterosexual dyad sometimes generates the old-fashioned, warm, and supportive setting portrayed by the Waltons on television but too often creates the type of modem American home that was recently described in the media as being surpassed in violence only by a battlefield or a riot. Most important, especially in the family context, close heterosexual relationships constitute the most significant settings in which social attitudes, values, and skills are acquired and exercised.

In presenting this conceptualization of the close personal relationship I do not mean to suggest that it is the only possible way to view these relationships for scientific purposes. However, what follows does take account of what I believe to be the central and unique phenomena to be observed in such relationships. This can best be illustrated by considering two brief scenarios of important events within close relationships.

Consider first Bill and Jane, a young university couple. They have been going together off and on for almost two years, and Bill is deciding whether or not to ask Jane to marry him. If he does it means making a commitment to her, breaking off with old girlfriends, and giving up some of his current freedoms. He thinks over their times together and the things Jane has done for his sake. He remembers how wonderful she can make things for him. As he recalls these occasions, he realizes that they have often enjoyed the same things. At the same time he recognizes that some of the things she has done for his sake were probably not things she would have chosen to do herself. He also remembers similar occasions on which he has made sacrifices for her. He thinks of what a good person she is and, in view of her apparent joy at seeing him happy, how much she seems to love him. He senses that she has already made some commitment to him and will be receptive to the idea of extending that commitment into an exclusive relationship. He also knows his own pleasure at seeing her happy. So he decides he wants to “take the leap” (make the final commitment) and propose marriage.

In this example, we see evidence of three essential elements of the personal relationship:

(1) Interdependence in the consequences of specific behaviors, with both commonality and conflict of interest: Bill thinks of his dependence on Jane, as evidenced by the importance to him of specific things she had done for him and with him. His decision is whether or not to let himself become more dependent. She also seems to be dependent on him. Though they may share many interests, there are also times in their relationship when what one wants is not what the other one prefers.

(2) Interaction that is responsive to one another’s outcomes: On certain occasions when they have different interests, she has been aware of his desires and has set aside her own preferences and acted out of consideration of his. In lay language, she has “gone out of her way for him” or even perhaps “put up with a lot from him.” To use other everyday terms, she has shown sensitivity to and considerateness of his needs.

(3) Attribution of interaction events to dispositions: Bill’s decision follows his attribution to Jane of certain stable and general causes—her dispositions. These include stable preferences and interests compatible with his but, more important, attitudes of love toward him. Her love will last (in common parlance) “through thick and thin” and will “govern all”—that is, control her actions in a variety of situations. Bill probably also attributes stable attitudes to himself: for example, he feels he will always love her. Both the attributions to her and those to himself imply that he can accept his dependence on her and even permit it to increase.

The negative side of a personal relationship, shown in a conflict episode, involves the same three elements. The following incident is rather trivial and certainly less significant for the relationship than the preceding example, but it will serve our purpose. It concerns a small part of the lives of Mary and Dan, a young working couple who live together. Specifically, when Dan uses the bathroom he leaves it in a mess, with towels scattered around, a ring in the washbowl and tub, and so forth. Mary asks Dan not to mess up the bathroon in this manner. Two days later he repeats his usual performance as if Mary had said nothing. She becomes very angry. (On his side, he can’t understand what she’s so upset about. He had merely forgotten to do what she had asked.)

Referring to the three properties listed earlier:

(1) In this example we see Mary’s side of the interdependence. Dan does something Mary strongly dislikes. Her outcomes are affected by his actions. There is also conflict of interest: Apparently he himself doesn’t care about bathrooms being in a state of messiness or at least not enough to expend the effort to clean up after himself.

(2) There is a failure on Dan’s part to be responsive to her outcomes. Knowing what she wants of him (in fact, having been told), he has failed to override his habits, preferences, or laziness out of consideration for her desires.

(3) The story doesn’t say so explicitly, but Mary probably makes attributions of Dan’s behavior to stable dispositions. Her version of the story is probably: “He repeats his usual performance as if I had said nothing.” (Dan’s version is that he merely forgot.) When subjects are asked to give explanations for the event as she describes it, not surprisingly a majority of them attribute it to Dan’s stable properties: his traits (lazy, messy) or his attitude toward Mary (doesn’t care about her wishes, doesn’t like being told what to do). If she entertains any of these beliefs about the person with whom she is living, Mary’s anger is understandable.

In short, in this example of conflict we see the same three elements as in the earlier positive example. Here of course the conflict aspects of the interdependence figure prominently in the scenario. They provide the context within which Dan’s lack of sensitivity and considerateness is apparent. This instance of failure on his part is interpreted by Mary in relation to past or recent events: his messy behavior and her request that he discontinue it. The attribution she finds appropriate for the event suggests that Dan’s stable dispositions are not those of a person with whom an interdependent existence will be easy.

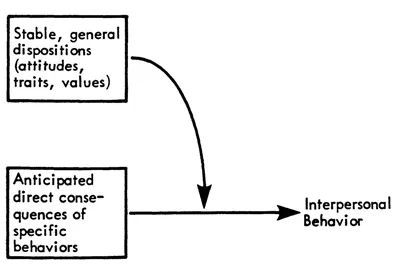

If we examine the three phenomena listed earlier and consider the relations among them, we gain two important insights into the relationship: First, the participants make a partitioning of the causes for the events in their interaction. That is, they make a distinction between the anticipated immediate incentives for behavior—its perceived direct consequences—and stable, general causes—what I have referred to as personal dispositions, which include attitudes, traits, and values. Second, the participants assume that the dispositional causes are manifest in behavior that is responsive to the partner’s outcomes and that therefore sometimes departs from the actor’s own immediate interests. These two aspects of the participants’ beliefs about the causes of behavior in their relationship are shown schematically in Fig. 1.1 The partitioning of causes is shown at the left, the behavioral events in the interaction being affected jointly by anticipated direct consequences and by dispositions. The latter are seen to affect or modulate the causal link between the direct consequences and the enacted behavior. For this reason the dispositions are to be inferred from discontinuities between the direct consequences to the actor and the behaviors he enacts. These assumptions about the causes of interpersonal behavior are most clearly apparent when the participants (a) scan behavior for how it departs from the actor’s own immediate interests (its direct consequences for him), (b) interpret such departures in terms of the actor’s responsiveness to the partner’s interests, and (c) explain patterns of this responsiveness in terms of such things as the actor’s attitudes toward the partner.

FIG. 1.1. The participants’ assumptions about the causes of interpersonal behavior.

We now come to an important choice point in our analysis. Are we to take the participants’ assumptions in Fig. 1.1 as reflecting merely a subjective reality or “story” that they typically develop about their relationships but that has little to do with the hard realities of their interaction? Or are we to take them as reflecting the real, underlying structure of these relationships and therefore indicative of how we should conceptualize it?

The former might be suggested by the comments of Weiss, Hops, and Patterson (1973) about conflictful marital relationships, that in most cases “a considerable amount of mutual training in vagueness has … taken place and … assumptions and expectations about the spouse overshadow the data at hand [p. 309].” The partners usually fail to label contingencies governing the mutual behavior, and “rely heavily upon a cognitive–motivational model of behavior. Thus, ‘intent,’ ‘motivation for good or bad,’ ‘attitude,’ etc., are all invoked to ‘explain’ the behavior of the other [p. 310].” Accordingly, the couple must be helped to set aside these explanations and to pinpoint the specific behavior-consequence-behavior sequences that get them into trouble.

Although admitting that the above view may be appropriate for relationships observed in clinical practice, I am inclined to take a different view of more typical personal relationships. Specifically, I emphasize that the subjective realities—the perceived intentions and attitudes—are of crucial significance in their development and functioning. Inappropriate causal explanations may indeed play a detrimental role in distressed relationships, and attention to specific behaviors and their consequences may be necessary if a battling couple is to break out of a vicious cycle of mutual aggression. However, in more normal relationships and particularly in those that attain high levels of mutual satisfaction, the “cognitive—motivational model of behavior” (as in Fig. 1.1) provides the basis for both their smooth functioning and the enjoyment of their deepest gratifications.

In short I have chosen to take Fig. 1.1 as indicating how the personal relationship should be conceptualized. The participants’ scanning of behavior for its responsiveness to the partner’s versus the actor’s interests, and their explanation of this responsiveness in terms of stable dispositions constitute important processes that control behavior and affect in the relationship, are based on objective structures of the relationship, and give rise to other structures.

From this perspective we can review the concepts and evidence regarding the personal relationship under three headings (corresponding to the next three chapters) that parallel the three earlier points:

(1) The structure of outcome interdependence: This is an analysis of the interdependence between the persons in regard to their immediate concrete outcomes. This is the basic structural foundation of their relationship, defined by how they separately and jointly affect one another’s direct outcomes.

(2) The transformation of motivation: responsiveness to patterns of interdependence. This is an analysis of the manner in which the persons’ interaction is responsive to patterned aspects of their interdependence, each one’s behavior being governed not only by his/her own outcomes but by the other’s outcomes as well. By virtue of its partial independence of the actor’s own immediate outcomes, pattern-responsive behavior constitutes in effect a transformation of the interdependence structure defined by those outcomes. Thus we must consider the processes that give rise to and mediate such transformations.

(3) The attribution and manifestation of interpersonal dispositions: This analyzes the manifestation in interaction, and particularly in its departures from and transformations of the basic interdependence structure, of relatively stable and general properties of the two persons. These are referred to as interpersonal dispositions because of their unique relevance to interpersonal relations.

In reviewing the evidence under these three headings I present some of the facts that have led to the points emphasized in the foregoing. After examining these three sets of ideas we can finally return (in chapter 5) to our original problem and attempt to outline a model of the relationship. This constitutes a technical elaboration of Fig. 1.1 and a suggestion of the interrelations among the structures and processes it implies. At that point we consider how persons are interdependent in regard to their dispositional properties. Thus in our elaboration of Fig. 1.1 we consider interdependence not only at the specific level but at the general level as well and examine the relations between the two levels. Our model, then, is cast in terms of levels of interdependence and the processes linking the levels.

The concepts I employ are found for the most part in prior writings by John Thibaut and myself. These will be indicated where appropriate. To provide a historical context for the analysis, it may be noted that its three key ideas also occur in the writings of earlier social psychologists. The grandfathers for these focal concepts are, respectively, Lewin, Asch, and Heider. In his papers creating the field of group dynamics, Kurt Lewin (1948) emphasized that interdependence among its members is the essential, defining property of a group. Lewin specified interdependence in a variety of ways, but particularly appropriate for us is his description of interdependence in satisfying needs, exemplified in his analysis of marriage partners (pp. 84–102). From this notion stemmed Deutsch’s conceptualization of interdependence between persons in locomotion toward their respective goals. We see later some of the consequences of the important comparison that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Structure of Outcome Interdependence

- 3. The Transformation of Motivation: Responsiveness to Patterns of Interdependence

- 4. The Attribution and Manifestation of Interpersonal Dispositions

- 5. A Levels-of-Interdependence Model of the Personal Relationship

- 6. Concluding Remarks

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Personal Relationships by Harold H. Kelley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Geschichte & Theorie in der Psychologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.