![]()

Chapter 1

The earliest development

From conception to birth

Conceiving a baby, nurturing a baby, giving birth, then guiding the child through toddlerhood and early childhood are different stages in what should be a wonderful process. It is certainly awe-inspiring and exciting as well as daunting. For, of course, alongside the pleasurable anticipations, parents, especially first-time parents, have many questions, e.g. ‘What happens during my baby's development both before and after birth?’, ‘What do I need to know about babies?’, ‘What can I do to give my baby the best start in life?’ and even ‘Who determines whether it is a boy or a girl?’ Often parents think ahead and wonder, ‘Will the things our baby inherits from us influence how they will grow and learn and behave?’ These are vitally important concerns and this chapter will set out to answer questions like these so that parents, professionals and other carers may understand the sequence of events that bring bodily and lifestyle changes for mothers, babies and indeed the whole family. This understanding will support professionals in recognising how family events can impact on the behaviour and learning of the children in their setting. The information will also help them to know what planning and timing of input is most appropriate. In this way they can ensure that each child has the best possible start in life.

Professionals who will share in the care and education of young children have many questions, too. Much of the literature on early childhood development (e.g. Bee and Boyd 2005) claims that babies learn even before they are born. So questions such as ‘How can this be and what are they learning? And in what ways does this early learning contribute to competence later on?’ need to be answered. Professionals, who form key parts of the ‘nurture’ scenario for little children, are always fascinated by the perennial questions that source many pieces of research, for example, ‘What parts do nature and nurture play in children's development and how does one influence the other?’ These kinds of ‘educational’ questions are very similar to those posed by the parents and they show how professionals, who will hopefully be working together with the parents, need to understand the developmental process from the very start.

Such understandings are also the foundation stones of strong parent/professional relationships. These develop through professionals getting to know and respect the family and the home environment as well as the child, while the family in turn builds relationships that allow them to frankly share joys or concerns about their child's progress. When confidence and trust are established, professionals may well be asked to give advice on the ‘best ways’ of supporting the child's learning at home. How can they do this if they have not learned about the experiences the parents have had and understood the child's background? It is also important that professionals understand and respect the relative contributions that homes and settings make towards the children's optimum development. In this light they are enabled to communicate appropriately with the parents in terms of their cultural, social and economic mores.

Those who are embarking on further academic study will have more questions, e.g. ‘In what ways is an academic study enriched by studying life before birth?’ One brief answer to this must be that the observations professionals make of children in their care are enhanced by understandings of how they come to be as they are, and this might mean appreciating the effects of birth traumas or disabilities. Learning is a lifelong process and when professionals become involved, it has already begun. They need to recognise what very different children know and understand and consider that in context, i.e. in relation to the life experiences the children have had. This is the best basis for planning new individual challenges and experiences, and interventions. On a more personal level, they need to appreciate where the children are coming from, i.e. the background and expectations of their particular culture, if they are to respond to them respectfully.

So, let's begin and discover what questions parents and carers and professionals ask. First-time mother-to-be Lisa wonders:

Q: What actually happens at conception? How does the baby develop in the earliest days? How important is the environment in supporting the child?

A: There are really three questions here. Let's look at conception first and then we'll talk about early development and the first environment, the womb.

The first step in the development of a baby happens at conception when a single sperm cell from the millions the father produces at ejaculation pierces the wall of the ovum from the mother. A new life begins.

The mother only produces one egg cell per month from one of her two ovaries. This happens midway between two menstrual periods. If the egg cell is not fertilised, it travels from the ovary down the fallopian tube and disintegrates, to be flushed away at the next period. If intercourse occurs during the vital few days when the ovum is in the fallopian tube, a single sperm will travel through the women's vagina, cervix, uterus and fallopian tube before penetrating the wall of the ovum. This results in a child being conceived, although only about half of that number will survive to birth.

Q: I understand that conception happens when the sperm and egg merge and the resulting pregnancy lasts for nine months. Is the baby safely in the womb from the moment of conception?

A: Conception takes place two weeks after a menstrual period and the time from then to the baby's birth is 265 days. The developmental changes that occur over that time are caused by an inbuilt or innate maturational timetable. Most doctors will talk about pregnancy lasting 40 weeks (i.e. taking the date from the date of the last period), but there are really 38 weeks gestation from the point of conception.

These 38 weeks are subdivided into three stages that GPs usually call trimesters. New mothers-to-be are often wary of spreading the news of the impending arrival until the first trimester is safely over because then they feel the baby has safely taken hold. They may also be aware that many fertilised ova do not survive and that miscarriages are relatively common in the early weeks. In fact, many women can miscarry without having realised they were pregnant.

Embryologists, however, tend to subdivide the 38 weeks according to the three stages of development.

Q: Three stages? What are they?

A: These are the germinal stage, the embryonic stage and the foetal stage.

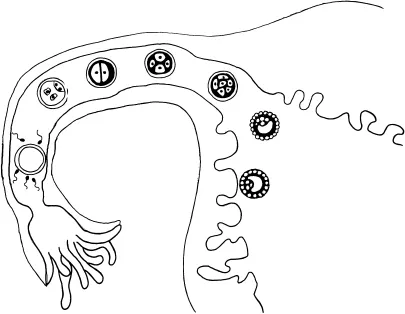

At the germinal stage, in the first 24–36 hours after conception in the fallopian tube (see Figure 1.1), cell division begins and in two or three days a clump of undifferentiated cells the size of a pinhead appears. Four days or so later, this organism, now named the blastocyst, begins to subdivide and separates into two rings. The outer ring of cells forms the support structures for the baby and the inner ring of cells forms the embryo itself. As this occurs, the cell ring travels along the fallopian tube and enters the uterus. There, the outer ring of cells in the blastocyst on contact with the uterus opens and tendrils attach themselves to the uterine wall. This process is called implantation.

Figure 1.1 The first ten days of gestation

The embryonic stage lasts for six to ten weeks after implantation. This is the time when the support structures develop. Two critically important ones are the amnion, a sac filled with amniotic fluid in which the developing foetus grows, and the placenta, a mass of cells that lies against the uterus. The placenta is formed very early and carries out the functions of the liver, lungs and kidneys for the embryo and later, the foetus.

Q: So are there still hazards or is the pregnancy safe now?

A: There are still potential problems, depending on the mother's lifestyle. This is why ongoing advice about not smoking or taking drugs is in all the magazines and leaflets at the medical centres.

Q: What happens when there are challenging lifestyles?

A: Well, the umbilical cord connects the circulatory system to the placenta and it acts as a bridge and a filter, supplying the foetus with nutrients from the mother's blood and taking waste matter back so that the mother can eliminate it. This filter is critical because it acts as a safety net. Unfortunately, some viruses do pass through and they attack the placenta, reducing the supply of nutrients to the developing embryo. However, other viruses are too large and are eliminated by the mother. Some drugs, alcohol and some illnesses also pass through and these impact on the baby's well-being. This is why mothers are encouraged to adopt the healthiest diet and lifestyle possible before conception and at all times during pregnancy.

In the past, it was thought that most ‘negatives’ or harmful substances were filtered out. Rubella, a form of measles, has been known to be potentially harmful to the baby's hearing and vision if the mother caught the illness in the first three months when the baby was developing fast. Later in the pregnancy, catching this illness did not have the same effect – the timing of the infection was critical. This understanding led to girls being vaccinated against German measles by their sixteenth birthday. Mostly, however, it was thought that the baby cushioned in the womb was ‘safe’, taking all its necessary requirements from the mother. An old saying was ‘lose a tooth for every child’, suggesting that the embryo ‘took’ all the necessary calcium and left mothers with toothache.

Nowadays, the effects of alcohol, smoking and drug taking during pregnancy may be seen in the newborn child, proving that the filter is not totally effective and that many harmful substances, e.g. cocaine, find their way into the baby's developing systems. In extreme cases newborns can have foetal alcohol syndrome, one of the most common causes of intellectual retardation. Others have to go through drug withdrawal and suffer fitting and tremors and subsequent communication and/or learning difficulties. ‘About a third of all cocaine exposed babies are born prematurely; they have low birth weight and show significant withdrawal symptoms after birth’ (Hawley and Disney 1992: 1–22). The long-term effects are still being researched.

Q: When does the heart begin to beat?

A: At four weeks’ gestation, there is a heartbeat even though the embryo is only about 2in. (5cm) long (Bee and Boyd 2005). The embryo itself is forming by differentiating the initial mass of cells into specialist groups that will become skin, nerve cells and sensory receptors, internal organs, muscles and the circulatory system itself. Eyes and ears are beginning to be formed, the mouth can open and close, and there is a primitive spinal column.

The foetal stage, when the nervous system develops, lasts for the remaining seven months, and this is the time when systems and structures are refining and strengthening (see Table 1.1 below). The nervous system develops most at this stage. During foetal development the brain develops bulb-like at the upper end of the neural tube that forms the spine (Carter 2000). The main sections of the brain, including the cerebral cortex, can be seen at seven weeks after conception and by birth the baby will have 100 billion neurons. However, these neurons are not yet mature, so they don't have the capacity to communicate with one another to make things happen. Maturation is the sorting of the neurons into similar groups that can work together to achieve some end.

In potential premature births paediatricians do their utmost to keep the baby in the womb until at least 28 weeks. This is because the nervous system and other vital organs are viable then and so babies are likely to avoid developmental difficulties.

Q: How is the genetic material from each parent passed on?

A: Unless there is a genetic abnormality or an accident in cell division, the nucleus of each cell in the body will contain 46 chromosomes arranged in 23 pairs and these carry all the genetic or inherited information. The sperm and the egg are different, however. These specialised cells, called gametes, have a final divisive stage (meiosis) in which each new cell receives only one chromosome from the original pair. So each gamete has 23 chromosomes, not 23 pairs. The sperm brings the genetic material from the father and the egg contains the mother's genetic endowment; these combine to form the 23 pairs that will be part of each cell in the new baby. In other pregnancies this material will be different. This means that each baby has a unique genetic blueprint that will influence what they will be able to do. Parents often exclaim that their children are ‘as different as chalk and cheese’ and the reason why this is true is because in subsequent pregnancies, each child will have inherited a genotype all of their own.

The genotype (i.e. the specific set of instructions contained in the genes) holds the child's individual characteristics such as body build, hair colour, some aspects of intelligence, and temperamental traits such as resilience or vulnerability, shyness or outgoingness, or extraversion. Some learning difficulties can be inherited too, e.g. dyslexia, dyspraxia or autism, and children can be born with a propensity to some illnesses, but it is by no means certain that these will develop. Knowing the possibility of serious illness, however, should encourage potential parents to be tested and being aware of the signs can allow them to seek immediate medical help should the need arise.

The phenotype, on the other hand, is the set of characteristics observed after birth and is a product of the genotype, i.e. the nature side of development, the environmental influences from the time of conception (the nurture side) and the interaction of the two. So, although a child could have a genotype for special gifts or talents, this potential could be damaged by the mother taking drugs during her pregnancy. As a result, her child could become a low achiever. This is why the quality of the first and subsequent environments is critically important and why all mothers should take steps to ensure that they give their baby the best possible start.

Q: Is there a timetable for prenatal development? Is this why scans are done?

A: The prenatal timetable (see Table 1.1) is the same for all children in all cultures, and scans provide a way of checking that prenatal development is proceeding well.

Q: Who determines the sex of the baby? My partner is anxious to have a daughter. If we had a son, would my partner be to blame, he wonders?

A: Earlier, we spoke about the 23 pairs of chromosomes that were paired in each of our cells. In 22 of...