- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Athenian Democracy

About this book

The fifth century BC witnessed not only the emergence of one of the first democracies, but also the Persian and the Peloponnesian Wars. John Thorley provides a concise analysis of the development and operation of Athenian democracy against this backdrop. Taking into account both primary source material and the work of modern historians, Athenian Democracy examines:

* the prelude to democracy

* how the democractic system emerged

* how this system worked in practice

* the efficiency of this system of government

* the success of Athenian democracy.

Including a useful chronology and blibliography, this second edition has been updated to take into account recent research.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Athenian Democracy by John Thorley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Greek Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

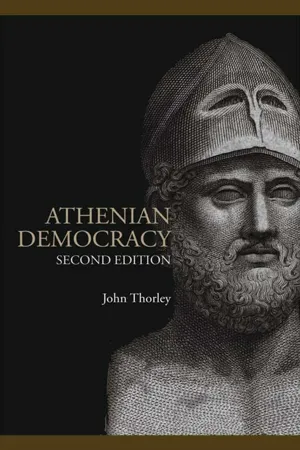

Map 1 Greece, the Aegean and Ionia

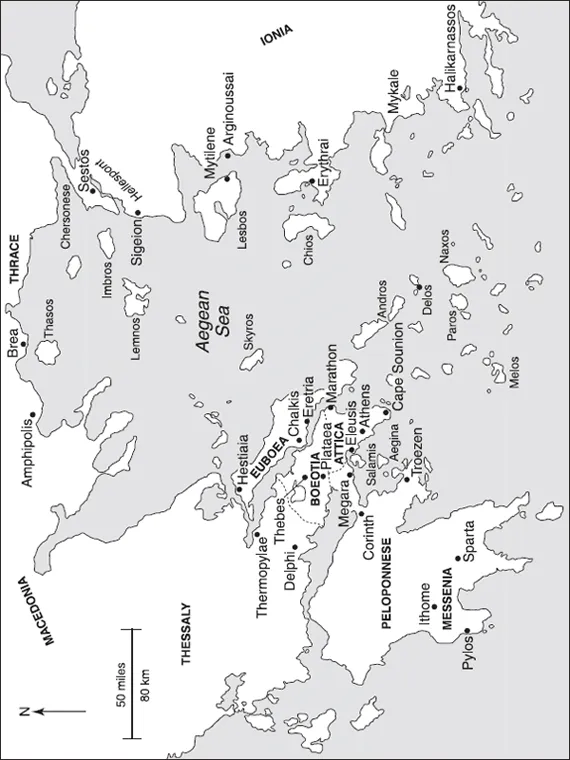

Map 2 ATTICA: City, Coast and Inland regions as defined by Kleisthenes’ reforms of 508/7 BC

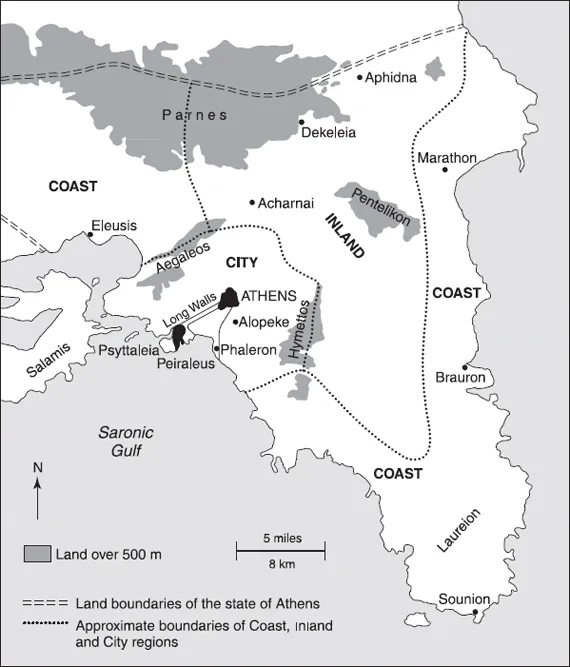

Map 3 ATTICA: City, Coastal and Inland trittyes

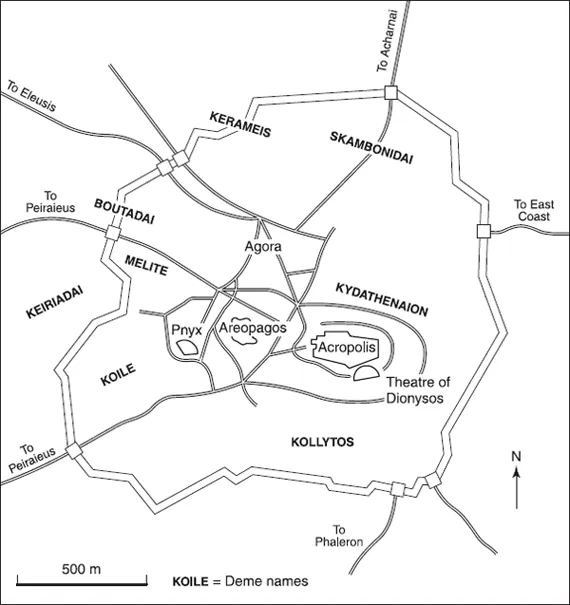

Map 4 The city of Athens

1

INTRODUCTION

In the fifth century BC Athens and the rest of Attica had a total population of probably around 250,000–300,000. Attica measured about fifty miles from the border with Boeotia in the northwest to Cape Sounion in the south-east, and about thirty miles from Eleusis in the south-west to the northern tip of the Bay of Marathon on the north-east coast (see Map 1). This is roughly the same population and geographical size as, in England, Carlisle and the northern half of Cumbria, or Norwich and the eastern half of Norfolk, or, in the United States, about half the size of the state of Delaware. What is remarkable about the small state of Athens and Attica is that 2,500 years ago its inhabitants created, for a period of about two hundred years, a society of such vision and achievements that they have ever since been the subjects of detailed study and, almost universally, of admiration. What did the Athenians do to deserve such attention?

Until the fifth century the achievements of the people of Athens and Attica were in fact not particularly distinguished. Athens and Attica had been united into one city-state probably during the course of the eighth century BC. The local tradition was that the unification had been achieved by the legendary king Theseus well before the Trojan War (which would put it around 1300 BC during the Mycenaean period), but if this does reflect a historical reality it is nevertheless likely that the unification had to be re-done after the chaos which followed the collapse of the Mycenaean kingdoms. The eighth century is no more than a reasonable guess; it may have been earlier, though hardly later. But then from the eighth to the middle of the sixth century, when many other city-states were busily establishing colonies around the shores of the Mediterranean and into the Black Sea, Athens was strangely uninvolved. Perhaps the citizens of Athens and Attica did not feel they needed to spread overseas; perhaps they were just not organised enough to do it. Again, in the field of literature the seventh and sixth centuries saw the flowering of lyric poetry (poems by a solo performer accompanied by a lyre or other instrument) in most parts of the Greek-speaking world. We have substantial fragments from about twenty poets, from Ionia, from the Aegean islands, from Sparta and Megara, and from South Italy. But from Athens we have only Solon (the great constitutional reformer) and, if one is prepared to go down to 500 BC, a shadowy figure called Apollodoros who is now represented by just a line and a half. Of the known philosophers of the sixth century (and we have substantial information about Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, Xenophanes, Herakleitos and Pythagoras, all of them from the Ionian coast of Asia Minor) not one apparently even visited Athens. We certainly do not get the impression that Athens (and by that we now mean Athens and Attica) is the centre of Greek culture in the eighth, seventh, or sixth centuries. But the fifth century is something quite different, and we must seek explanations.

Any explanations of a complex phenomenon such as fifth-century Athenian culture will themselves be complex, but underlying the phenomenon is the political system which the Athenians shaped for themselves, their democracy. It would be far too simplistic to suggest that the democracy was the sole reason for the flowering of Athenian culture, if only because other states later developed democracies but did not suddenly flourish culturally. But Athenian democracy was very much the model to be followed by those states who wanted to give democracy a try. It was in many ways a radical democracy, and it was seen by many, probably most, Athenians as an integral part of their cultural achievements, as Pericles’ famous funeral oration in the autumn of 431 testifies (Thucydides 2.35–46).

The democracy was brought into being by Kleisthenes in 508/7 after thirty-six years of one-man rule in Athens by the tyrants Peisistratos, who was much respected for his abilities, and his son Hippias, who was hardly respected at all. The political background to Kleisthenes’ reforms and his likely motives will be analysed later; for the moment we may simply note that the changes were indeed revolutionary and gave all male citizens of Athens quite unprecedented powers - in fact absolute powers in a corporate sense - over policy, finance and the whole legal system, which is to say over the whole running of the state of Athens; and we may also note that Kleisthenes probably did not quite intend it that way! But the sudden change from one-man rule could hardly have been greater, and the Athenians took to their new system with great enthusiasm.

Only a few years later the Athenians were embroiled with the massive power of the recently founded Persian Empire, and the Persian Wars which followed moulded the minds of Athenians, inspiring them with self-confidence (which often appeared to others as arrogance) and offering opportunities for political power which they took with enthusiasm. In 498 Athens had helped the Ionian Greeks in their revolt against their new Persian masters, thus incurring the enmity of the Persian king, Darius, who sent a force to attack Attica. It landed at Marathon in 490 and was heroically defeated; 6,400 Persians were killed, with the loss of only 192 Athenians. Ten years later Darius’ son Xerxes sent a much larger force: an army of disputed size but undoubtedly very large by any standards and a fleet of over 1,200 ships, which attacked Greece along the coast of the north Aegean then into Thessaly and on to Central Greece. The Persians occupied Athens and totally destroyed the city after most of the population had been evacuated to the island of Salamis and to the friendly town of Troezen on the southern shores of the Saronic Gulf. The Spartan king Leonidas (one of the two kings of Sparta; they had a quaint system of two royal families) with his small force of Spartans had gained great glory by delaying the Persian advance at Thermopylae in Central Greece. But the decisive battle was the naval battle fought in the narrow waters round Salamis in the late summer of 480, where the mainly Athenian fleet defeated the superior numbers of the Persian fleet through the clever strategy of the Athenian Themistocles. The Persian land forces were still intact, though now in a difficult position, and were defeated at Plataea in Central Greece the following spring.

The importance of the Persian Wars for the development of Athenian culture is worth stressing. The Athenians remembered Marathon and Salamis as their finest hours; and the fact that one was a land battle and the other a sea battle was also of great significance, because while Marathon had been won by the hoplites, who came from the wealthier classes, Salamis had been won by the rowers of the triremes, who came from the poorer classes. Athenians saw the defeat of the Persians as a triumph for their democratic system of government.

And there was a further point - or rather two linked points. The Persians had destroyed the city of Athens, its houses, temples, public buildings and city walls, but the Athenian fleet of trireme warships was still largely intact. During the following years Athens established the Delian League consisting of most of the Aegean islands and seaboard towns of the Aegean as a defence against possible future Persian aggression, with its fleet as the great deterrent. But when Athens formally made peace with Persia in 449 and all pretence of a defence league was gone, the citizens of the democracy nevertheless had no qualms (or very few) about putting the annual revenues from their allies into rebuilding the temples of the city on a magnificent scale.

Art and architecture and drama and literature and philosophy flourished. And they continued to flourish throughout the Peloponnesian War which resulted from the increasing tension between Athens and the Peloponnesian League, a war which Pericles saw as inevitable. But he died only two years after the war began, and no such dominant leader was found to replace him. Athenian blunders, combined with increasing naval competence on the part of Sparta, led to the humiliating defeat of Athens in 404. Though a democratic system of government did continue in Athens, its empire was gone and so was its confidence.

Kleisthenes’ democratic system gave Athenian citizens quite unprecedented freedom to express their opinions and to make their own decisions. They were just learning to do this when the Persian Wars came along and not only left them with memories of heroic splendour but forced political opportunities upon them and convinced them of the superiority of their democratic system. It was against this background that the Athenians built their empire, developed their unique expression of civilisation and fought their wars. If we are to understand the history and cultural achievements of fifth-century Athens we must see how their democracy actually worked.

2

PRELUDE TO DEMOCRACY

ATHENS BEFORE SOLON

Thucydides, the great historian of the Peloponnesian War, asserts without question that it was Theseus, a king of Athens in the period before the Trojan War, who unified Athens and Attica into one polis. The process was traditionally referred to as sunoikismos, ‘living together’, and Thucydides describes it in some detail (Thucydides 2.14.1–2.15.2 and 2.16.1). Many modern historians have questioned Thucydides’ version of the sunoikismos, arguing that even if there was a Mycenaean unification of Attica it probably needed to be done again after the collapse of the Mycenaean world. There certainly seems to be evidence that Eleusis in the west and Marathon on the east coast were incorporated into Attica after the Mycenaean period, but this does not necessarily mean that Attica had been entirely fragmented and had to be reconstituted as a unified state. The truth may be that most of Attica did retain some kind of unity after the Mycenaean period, perhaps under the king’s of Athens, but that some extremities had to be reincorporated, perhaps during the eighth century; if it had been later than that one would have expected some clearer historical tradition of which Thucydides would surely have been aware.

In describing the process of sunoikismos Thucydides makes a point which we should always bear in mind about the population of Attica:

So for a long time the Athenians had lived in independent communities throughout Attica, and even after their unification the common experience from the time of the ancient inhabitants right down to the present war was to be born and to live in the country.

(Thucydides 2.16.1)

It is difficult to be precise because we simply do not have accurate statistics, but it seems very likely that the city of Athens itself (not including Peiraieus; there were some three miles of open fields between the two) contained no more than a fifth of the total population of the Athenian polis, perhaps 50,000 people in all. Most Athenians made their living from the land, or from trades associated with its produce.

How Attica was governed before Solon’s time is far from clear in detail, though we can trace the main outlines. Athenian tradition refers to a period of monarchy followed by rule by leading noble families through the Council of the Areopagos (the ‘Hill of Ares’ some 300 metres west of the Athenian Acropolis, where the Council met - see Map 4) with officers called generically ‘arkhons’ (simply ‘rulers’). To put dates to this process is difficult, but it seems likely that by about 700 the kings had gone and that the Council of the Areopagos (appointed by the powerful noble families from their own members) was effectively in charge.

In the early days after the removal of the monarchy there were apparently three arkhons, the Basileus (‘king’) in charge of religious and state rituals, the Polemarch in charge of war, and one called simply the arkhon, who had general administrative duties and was probably a slightly later invention than the other two, though he was actually the most powerful and the period of his office (later restricted to one year only) was named after him (he is therefore often referred to as the eponymous arkhon). Then six more arkhons were added, called thesmothetai (‘lawsetters’), who were in some way in charge of the state’s laws, though details remain obscure. By the time these latter were added the period of office of the arkhons had been reduced from ten years to an annual appointment, and it seems to have become established practice that ex-arkhons automatically entered the Areopagos. They were undoubtedly the chief officers of the state, aided by a collection of minor officials mainly for financial matters, and responsible perhaps to the Council of the Areopagos, but even this seems in no way to have been f...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Chronology

- Map 1: Greece, The Aegean and Ionia

- Map 2: Attica: City, Coast and Inland Regions as Defined by Kleisthenes’ Reforms of 508/7 BC

- Map 3: Attica: City, Coastal And Inland Trittyes

- Map 4: The City of Athens

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Prelude to Democracy

- 3 The Democratic System: Kleisthenes' Reforms

- 4 The Democratic System: Later Reforms

- 5 The System in Practice

- 6 An Overview

- Appendix 1 Kleisthenic tribes, trittyes, demes and Council members

- Appendix 2 Ostracisms

- Bibliography

- Index