![]()

1 What Is Baroque Music?

Western European musicians in 1700 would have been surprised to discover that the age in which they lived would eventually be known as the Baroque, and that this term would be applied to a stretch of time they would have considered so multifarious, so full of change and contradiction, as to make the idea of it falling under a single rubric an absurdity.

Unlike many historical terms that have been invented by scholars after the fact, the term baroque was applied to music as early as 1733. But that is almost the end of the age it describes, a 150-year period from approximately 1600 to 1750. Moreover, for eighteenth-century commentators, baroque was always a derogatory term. Anything considered grotesque, bizarre, excessive, or preposterous—whether it was a piece of music, a poem, a painting, or a building—was labelled baroque. To call an entire era “Baroque” would not have been a compliment.

Certainly the visual arts of the Baroque period—home to master painters Caravaggio, Rubens, and Rembrandt, the sculptor and set designer Bernini, and architects Borromini and Wren—tended to extravagance and excess. Churches from Rome to Krakow, in Poland, were outfitted with opulent ornaments, gilded putti or marble detail, dramatic contrasts of light-and-shade (chiaroscuro effects), and large ceiling frescoes featuring trompe l’oeil images rendered in so realistic a fashion that they tricked the eye into seeing what was depicted in three dimensions. Marian columns became a fashionable addition to church streetscapes and a vital display of public faith in Catholic Europe. One of the earliest is in the Piazza Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, which features a column from the ancient Roman Basilica of Constantine that was crowned in 1614 with a bronze statue honoring the Virgin and Child. Ornate versions of this column were erected in Munich, Prague, and Vienna, as a symbol of gratitude to the Virgin for her aid in ending plague or safeguarding the city from invasion or destruction during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48).

In one of the earliest applications of the term baroque to music, a reviewer of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Hippolyte et Aricie (1733) complains of its extravagant modulations, excessive repetitions, and whimsical metrical changes. The writer labels the opera baroque. Similarly, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Dictionary of Music (1778) defined baroque music as dissonant, unnatural, and having sudden changes in tempo and harmony. It is worth noting, however, that Rameau’s opera dates from the latter years of the Baroque era. The writer may be judging Rameau’s music by a standard that is already out of date; or he—like Rousseau—may be writing from the perspective of a new generation whose aesthetic preferences lie with the emerging, Classical style (another term that is equally convenient but imprecise).

Early historians continued to wind that negative thread through their writings on the Baroque period. The Swiss historian, Jacob Burckhard, who used baroque as both a stylistic-historical term and as a qualitative term, is a good example. In 1855, Burckhard—who would have had no trouble finding writers at the beginning of the seventeenth century who agreed with him—described the Baroque as the Renaissance “gone wild.”

From the early twentieth century onward, however, historians generally retreated from such pejorative judgments. The most influential application of the term baroque to music came from German musicologist Friedrich Blume (1893–1975). Blume believed that Baroque music was part of a larger Baroque Zeitgeist or spirit of the times. His “Fitness and Need of the Word ‘Baroque’ in Music History” (Document 1) was one of his most important writings to appear in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Music in History and the Present), a comprehensive music dictionary of 9,414 articles under Blume’s editorship. Blume raised fundamental questions about how we do history, and about the implications and validity of borrowing terms from other arts:

Figure 1.1 The piazza and basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome.

All future music historiography will be faced with the choice of either setting up purely musical style-categories labelled in purely musical terms that do indeed stand unequivocally for specific musical matter but remain dissociated from the intellectual ambiance and origin of these styles and intelligible only to the professional musician, or using to characterize its own style-periods and style-forms terms that are at the same time applicable in other fields and familiar to the non-musician also, even though because of this they suffer from a certain ambiguity. (Document 1)

For Blume, the advantages of baroque music outweighed the disadvantages of borrowed terminology.

It remains fair to ask: Why use the term now? Is it merely a convenience or are there common denominators that run through the art, music, literature, and architecture of this period that testify to an overarching unity of purpose?

Indeed the Baroque period does manifest a central code of aesthetics. It placed value on abundance, pleasure, variety, and the emulation of past masters. It also embraced the fundamental assumption that composers, artists, sculptors, architects, painters, and performers could (and ought to) influence the emotions of the audience, whether those emotions were in the service of the church, the state, an individual patron, or society at large. But we might also note that the means of swaying the audience was through representing an emotion: The viewers, or listeners, were not expected to be swept away by their feelings. Rather, emotions were objectified; one experienced them as states, and they were thus subject to rationalization and control—a very different way of looking at art and emotion than what one finds in the Romantic era, for instance.

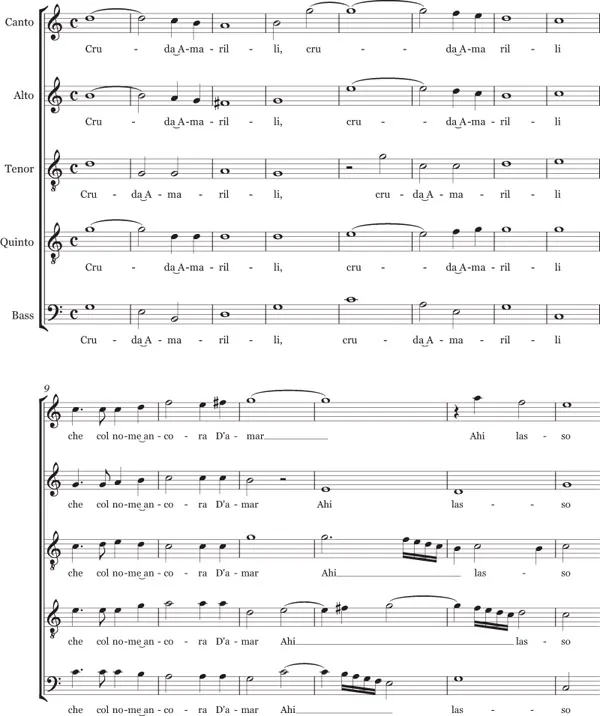

In music, we mark the start of the Baroque period with a number of important innovations: the invention of opera, the transformation of the polyphonic madrigal into solo and ensemble settings with instruments, the rise of solo singing, and a greater focus on natural declamation and expressing the meaning of the words. We see as well a shift towards chordal harmony, a freer treatment of dissonance, and a gradual disintegration of the modal system as composers begin to understand and exploit harmonic progressions in terms of what we call functional harmony. At the time, these changes appeared so radical that they incited heated debates. The madrigals of Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643), a young composer working at the ducal court in Mantua at the beginning of the seventeenth century, were especially contentious in the way they challenged conventional compositional practice, particularly as it pertained to dissonance. His madrigal “Cruda Amarilli” (Cruel Amaryllis) was immediately understood as a standard bearer for the new style. In it, Monteverdi deliberately wrote dissonant clashes between the soprano and bass to portray the cruelty of Amaryllis, whose bitterness is reflected in her very name (the Italian amare can mean either bitterness or love). He also left dissonances unresolved at cadences—a breach of harmonic protocol no Renaissance composer would have dared.

Such departures from standard practice so outraged the conservative theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi (1540–1613) that he protested against Monteverdi’s music in a series of pamphlets published to discredit the young composer. Monteverdi fought back with a rebuttal, released through his brother Giulio, and published as a preface to the composer’s Fifth Book of madrigals (1605) and, in expanded form, the Scherzi musicali (1607). Here, the Monteverdis argue that the text was paramount: “in this kind of music, it is his goal to make the words the mistress of the harmony and not its servant, and it is from this point of view that his work should be judged.”1 Textual meaning could only be captured by using more expressive harmonies, regardless of rules of counterpoint and voice leading. To distinguish the old style from the new, Monteverdi coined the terms first and second practice. The first practice referred to music that made “the harmony the mistress of the words,” thereby following stylistic norms of the Renaissance period. The second practice referred to music governed by the text: harmony “becomes the servant of the words.”2 The public nature of the dispute, and the obvious awareness that the earlier style was under siege by the modern, reinforces the general acceptance among musical scholars for starting the Baroque period around 1600.

When did the Baroque period end? As with those eras labelled Medieval, Renaissance, and Classical, the Baroque period did not end at a clearly demarcated point. New and old overlapped, and styles lasted longer in some regions than others. Italy, for instance, quickly adopted the concerto styles of Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) in the eighteenth century, while English composers continued to enjoy concertos based on earlier models by Arcangelo Corelli (1653–1713). Similarly, the dense, polyphonic fabric of German contrapuntalists like Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) overlapped with a new aesthetic that privileged melody and balanced phrasing. Issues of stylistic overlap and longevity were only heightened in the Americas, where European colonialism brought concerted and operatic idioms to Mexico in the early eighteenth century, decades after the genres’ induction on the Continent. Even as late as 1762, Christoph Willibald Gluck’s opera Orfeo ed Euridice was essentially a reaction to Baroque style, which survived in the institution of opera seria long after the galant had made serious headway in lighter forms of opera. But Gluck’s reform was also a return to opera’s roots. In sharp contrast to the elaborate but dramatically static da capo arias (ABA form) that dominated Baroque stages in the decades around 1700, Gluck’s simpler, less flamboyant music attempted to emulate the union of poetry and music the creators of opera at the beginning of the Baroque era had idealized as the ancient Greek theatrical practice.

Example 1.1 Monteverdi, “Cruda Amarilli,” mm. 1–14.

Geopolitics and Musical Style

The political and religious landscape of Baroque Europe was complicated and diverse, with multiple and competing models of governance. This situation was only enhanced when European powers embarked on a vast program of overseas colonization during the Baroque period, one that had profound impacts on the world economy and population.

Italy was the undisputed stronghold of Catholicism, which united a political hodgepodge of courts, city-states, foreign-held territories and the Papacy, with Rome at its center and the Pope at its head. Among the independent territories, the Republic of Venice enjoyed the greatest prominence, offering a unique governing model that was famous across Europe for its innovative approach to democracy. A similar range of political models characterized German-speaking lands, although there was far less agreement in religious affiliation.

The German-speaking lands were a political and religious mosaic of Lutheran, Calvinist, and Catholic dukedoms, princedoms, electorates, and free imperial cities. The region was held together under a nominal allegiance to the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation,” a territorial affiliation that was born with the coronation of the Frankish King Charlemagne as Roman emperor in 800 and lasted until the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars in 1806. Dynastic marriages and religious tolerance enhanced regional stability until controversy over succession erupted upon the death of Emperor Matthias (ruled 1612–19), who had no heir. The crisis sparked the Thirty Years’ War (1618−48), a bitter series of conflicts that drained the population and left many towns and cities in turmoil. France, Spain, Sweden, and Denmark joined the dispute in an effort to gain territory and wealth. The conflict finally ended with the signing of the Peace of Westphalia on October 24, 1648; the treaty granted the principle of cuius regio, eius religio: “Whoever rules the territory determines the religion.”

Under Louis XIV (1638–1715), France strengthened its monarchy and secured its position as a Catholic power in the Baroque period. Across the Channel, England underwent immense political, social, and religious change, overturning the political instability of the first half of the seventeenth century with the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660; by the end of the Seven Years’ War (1763) England was the leading state power. The most important political change for Spain, a vast territory that included Portugal, the southern Netherlands, and the kingdoms of Sardinia, Sicily, and Naples, was the transfer from Habsburg to Bourbon rule. With no offspring, Spanish king Charles II (ruled 1665–1700) willed his inheritance to Philip (1683–1746), grandson of Maria Teresa and Louis XIV.

Europe’s geopolitical landscape had a direct impact on the cultivation of music and culture during the Baroque period. Political crisis and instability brought with them reductions in musical personnel in England and parts of Germany during the Thirty Years’ War; in France, however, where musical establishments were considered part of the cultural machinery designed to strengthen the monarchy, they grew. Pockets of regional styles coexisted with international trends that swept across national, linguistic, and religious boundaries. The Catholic courts of Salzburg, Vienna, and Munich had especially close ties with Venice and Rome, where rulers sent agents to recruit the best singers and artists. Conflicts over religion and territory at times strengthened and at other times weakened cultural ties and musical migration. A good example of the former is the strong network of Lutheran courts operating in northern Europe. Bound by ties of marriage and religion, the Lutheran courts of northern Germany exchanged musicians with the court of King Christian IV of Denmark in the first half of the seventeenth century. Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672), chapel master at the electoral court of Dresden, traveled to Copenhagen to participate in the wedding festivities for Crown Prince Christian in 1634 and may have introduced Italian operatic singing to the far north during this visit. Musical practices in England at times worked independently of Continental influence but were at other times deeply engaged with European styles, whether in emulation or in an effort to mark a distinctly English path.

Europe’s geopolitical situation ensured a large pool of competing patrons: courts, churches, town councils, and cities. But why, despite the continual wars, religious tension, and the challenges of daily living, did patrons invest so heavily in music? In fact, periods of political and religious tension may have fuelled patronage. Art, whether it was music, theater, paintings, visual arts, or architecture, offered ruling powers a means of advertising not only their wealth and good taste, but the fact that theirs was a state secure enough to provide the leisure time for enjoying art. Cultural display was thus akin to modern-day public relations. Glorifying the ruler was the central strategy for artistic patronage. Then as now, glory was best bestowed through brilliant spectacle and lasting tributes.

By the eighteenth century, patterns of musical migration and competition forged with political and emerging nationalistic sentiments to create distinct and easily recognized musical profiles that are commonly referred to as national styles. An emblem of French style, for instance, was the stately overture that originated at the French court of Louis XIV, which was known and imitated across Europe by Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel (1685–1757), and Georg Philipp Telemann (1681–1767). Similarly, dense counterpoint came to be associated with German composers, particularly in the organ music of Dietrich Buxtehude (ca. 1637–1707) and Bach, while Italian music was praised for its melodiousness.

Musicians recognized and even debated the merits of national styles. The strongest clash came between proponents of the French and Italian styles, a battle waged off and on in print for decades. French cultural commentator Charles de Saint-Évremond (1613–1703) claimed that “the expressiveness of the Italians is false or at least exaggerated… . As to the manner of singing … no nation can rival ours.”3 This did not stop François Couperin (1668–1733) from combining the French and Italian styles to create a sophisticated stylistic hybrid in Les goûts réunis (The Styles Reunited, 1724). In the preface to the collection, Couperin...