![]()

Part One

Techniques of Political Repression in Nineteenth–Century Europe

![]()

Chapter 1

Suffrage Discrimination in Nineteenth–Century Europe

Universal suffrage, according to Danish Prime Minister Jacob Estrup (1875–94), a conservative landowner, was the “greatest folly in this otherwise so abundantly foolish age.” It would add, he stated, to “liberalism, radicalism, socialism and anarchism” and ultimately to the “collapse of everything we have learned. to respect and love” (Woodhouse 1974: 203). Similarly, François Guizot, the conservative premier of France (1847–8) termed universal suffrage “absurd.” Under such a system, he said, “Every living creature would be granted political rights” (Fejto 1973: 77). Conservative legislator Robert Lowe, in opposing a proposed expansion of the suffrage in the United Kingdom in 1866, declared, “It is the order of Providence that men should be unequal, and it is … the wisdom of the State to make its institutions conform to that order” (Smith 1966: 81).

Such sentiments were by no means confined to European conservatives during the nineteenth century. Until late in the century, most European “liberals,” who demanded extension of the suffrage to encompass the middle and professional classes, were among the most ardent foes of enfranchising the poor. Thus, the Whig (liberal) historian and parliamentarian Thomas Macaulay declared in 1842 that universal suffrage would be “fatal to the purposes for which government exists” and was “utterly incompatible with the existence of civilization” (Arnstein 1971: 32). The writer and social critic Thomas Carlyle termed universal suffrage the “Devil-appointed way” to count heads, one that would equate “Judas Iscariot to Jesus Christ” (Smith 1966: 242). Odilon Barrot, a leader of the liberal opposition to the Guizot regime in France, declared:

“Vox populi, vox Dei,” which gives to a majority the infallibility of God is the most dangerous and the most despotic absurdity that has ever emerged from a human brain. If you want to ruin a state, give it universal suffrage (Fasel 1970: 21).

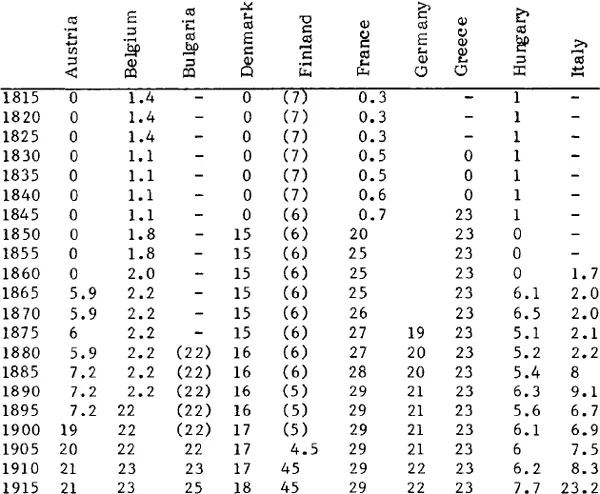

In fact, as Table 1.1 indicates, the great majority of European countries adopted highly discriminatory suffrage systems for lower legislative chambers for most or all of the 1815–1915 period. Universal male suffrage (which is what was meant when universal suffrage was discussed) at age 21 would have enfranchised about 25 per cent of the European population during the nineteenth century, while universal adult (including female) suffrage would have given the vote to about 50 per cent of the population. Female suffrage at the national level was not granted by any European country before 1915 save Finland (after 1906) and Norway (after 1907). While disenfranchisement of women reflected a general discrimination against rich and poor females alike, disenfranchisement of men was based clearly on class. As late as 1880, as a result of class–biased suffrage systems, less than 10 per cent of the total population was enfranchised in Austria, Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Table 1.1: Percentage of Total Population Enfranchised for Lower Legislative Chambers in Europe, 1815–1915

Explanations for Table 1.1: A dash (–) indicates this country did not exist as a geopolitical entity at the time. A zero (0) indicates the lack of a popularly elected national legislative assembly. Data enclosed in parentheses are estimated based on the provisions of electoral laws and/or known data for other dates. All other data are precise calculations or interpolations within known data. Had universal manhood suffrage been in effect, 20–25 per cent of the total population of each country would have been enfranchised; universal adult suffrage would have enfranchised 40–50 per cent of each country’s population. The figures for Denmark after 1910, Finland after 1905 and Norway after 1905 reflect total or partial enfranchisement of women. In Germany before 1870 and in Switzerland before 1850 the confederation legislatures were elected by state or cantonal governments, which themselves were elected on widely varying franchises. The data for Belgium before 1830 and for Hungary before 1870 are for provincial legislatures; until 1830 Belgium was part of the United Netherlands along with the Dutch Netherlands, and before 1867 Hungary was an integral part of Austria. Finland was under Russian sovereignty but had its own legislature throughout the 1815–1914 period. Norway was united with Sweden through allegiance to the Swedish king, although autonomous in domestic affairs, until 1905. Belgium (1893–1919), Austria (1861–1907), Rumania (1866–1917), and Russia (1905–1917) all used class–weighted voting systems (see text for explanation).

Major sources: Mackie and Rose 1974; Rokkan and Meyriat 1969; Anderson and Anderson 1967: 320; Garver 1978: 349; Rokkan 1967; Wandwycz 1974: 318; Rothschild 1959: 44; Dedijer 1974: 379; Payne 1973: 474, 543; Seton–Watson 1934: 357; Seton–Watson 1972: 467; Kent 1937: 26; Neufeld 1961: 524; Walker 1973.

The clear purpose of the class–biased suffrage systems that prevailed in most European countries for all or part of the nineteenth century was to protect the wealth and power of the dominant elements of European society. This purpose was rarely articulated as directly as Macaulay’s warning that the “populace” would use political power to “plunder every man in the kingdom who had a good coat on his back and a good roof over his head” (Langer 1969: 55). Instead, disenfranchisement of the poor, or the extra–weighting of the votes of the wealthy if the poor were enfranchised, was usually justified by more lofty and less obviously self–interested principles. The primary justification, repeated over and over again by both conservatives and liberals, was that wealth and property were signs of intelligence and ability, and that it was only reasonable to entrust the control of state policies to those who had demonstrated their qualifications by material well-being. Since, according to this argument, any talented person was capable of acquiring wealth, the denial of universal suffrage did not discriminate against poverty, but against ignorance, sloth and general incapacity. Thus, “enrichissez–vous” (get rich) was the solution made famous by Guizot for those who complained they could not vote under the French laws that disenfranchised over 99 per cent of the population before 1848.

The thesis that wealth and property were the best indicators of electoral ability was so frequently espoused that Spanish liberals noted in the prologue to their 1837 electoral law—which disenfranchised 98 per cent of the population—that “in all the nations of Europe which have proceeded us in the ways of representative government, private property has been considered the only proper indication of electoral capacity” (Marichal 1977: 105). In blunter terms, a member of the Spanish legislature told that body in 1845 that poverty was a “sign of stupidity” (Carr 1966: 237), and Italian Prime Minister Francesco Crispi (1887–91, 1893–6) told his parliament that the common people were “corrupted by ignorance, gnawed by envy and ingratitude, and should not be allowed any say in politics” (Smith 1959: 175). Francisco Romero Robledo, who became notorious for his election rigging as minister of the interior in late nineteenth–century Spain, told the Spanish legislature in 1876:

I have fought universal suffrage all my life because I consider it to be an instrument of tyranny and an enemy of liberty. Suffrage is not an independent right but a political function that demands conditions of capacity and most Spaniards do not have sufficient culture or intelligence to understand the public interest when they deposit their slip of paper in the electoral urn (Kern 1974: 38).

Supplementing the argument that wealth per se was a sign of electoral capacity was a related and sometimes intertwined argument that the wealthy had more of a stake in and made more of a contribution to society, and therefore were more deserving of a say in determining governmental policy. Thus, the Prussian aristocrat Baron Adolf Senfft von Pilsach declared:

I cannot consider it just and reasonable that a simple working man has as much voice as his employer who hires hundreds or thousands like him, gives them bread and feeds their families (Hamerow 1974: 211–12).

When a class–weighted voting system was introduced in Prussia in 1849, the Prussian ministry defended it as allowing the “several classes of the people that proportional influence corresponding to their actual importance in the life of the state” (Anderson and Anderson 1967: 307). When a similar system was introduced for local elections in Russia in 1864, the government noted that voting was based on the principle that “participation in the conduct of local affairs should be proportionate to everyone’s economic interest” (Mosse 1962: 79).

Another argument used to justify restricting or biasing the suffrage in favor of the wealthy was that those with money were most qualified to determine public policy because only they had enough leisure to carefully consider affairs of state. Thus, the leading French Restoration liberal–radical Benjamin Constant declared:

Those whom poverty keeps in eternal dependence and who are condemned to daily work are no more enlightened on public affairs than children. … Property alone, by giving sufficient leisure, renders a man capable of exercising his political rights (Artz 1929: 206).

A final argument used by those opposing a broad suffrage was that the wealthy would pursue a “disinterested” approach to politics since their affluence allowed them to ignore their own interests, while the poor would always be influenced by their need to obtain more money and would always pursue selfish policies. This argument sounds ludicrous today, since the basic purpose of class–biased suffrage systems was precisely to preserve the existing structure of power and wealth, an aim hardly disinterested from the standpoint of those who benefitted from that structure. Nevertheless, it was made frequently and perhaps even innocently by those whose vision was so clouded by upper–class bias that to them such a system was normal and anything else was clouded by selfish interests. Thus, one of the great British aristocrats, Lord Robert Cecil, who as the Marquis of Salisbury served three times as prime minister (1885–6, 1886–92, 1895–1902), argued that only by preserving political power for the wealthy would politics “not be defiled by the taint of sordid greed.” Under a democratic suffrage, he maintained, “passion is not the exception but the rule,” with power entrusted to those whose minds “are unused to thought and undisciplined to study.” Under such a system, he argued, “the rich would pay all the taxes and the poor make all the laws” (Tuchman 1967: 11).

Suffrage Discrimination for Lower Legislative Chambers

The most common device for excluding the poor from voting for lower legislative chambers was to make the franchise dependent upon a minimum amount of income, a minimum amount of property, and/or the payment of a minimum amount of direct tax based on property or income. Thus, under the French constitution of 1814–30, to vote one had to pay 300 francs ($60) per year in direct taxes, a requirement that reduced the electorate to less than 100,000 (about 0.3 per cent) in a population of about 30 million. Following the July 1830 revolution in France—partly sparked by the attempt of King Charles X (1824–30) to reduce the suffrage to about 25,000—the franchise was slightly liberalized. Under the 1830 constitution, which remained in effect until universal male suffrage was introduced in 1848, the direct tax requirement was reduced to 200 francs per year, thus enfranchising in 1842 about 220,000 people in a population of 34 million.

More or less similar systems were the norm for most European countries during all or most of the nineteenth century. Thus, in Belgium, the suffrage under the electoral law of March 1831 depended upon a direct tax payment requirement that enfranchised fewer than 50,000 Belgians (about 1 per cent) in a population of 4 million in 1831. In 1848, the tax requirement was liberalized, increasing the eligible Belgian electorate to about 80,000 in a population of 4.5 million. The 1848 law remained in effect until 1893, when Belgium adopted a system of universal male suffrage with extra votes for the wealthy and highly educated.

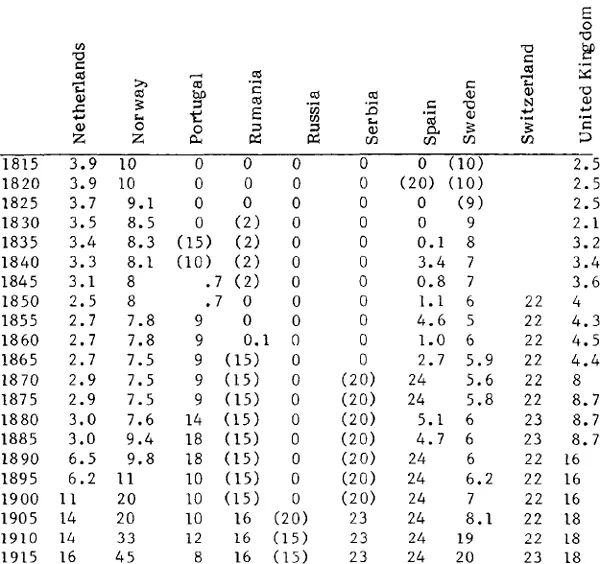

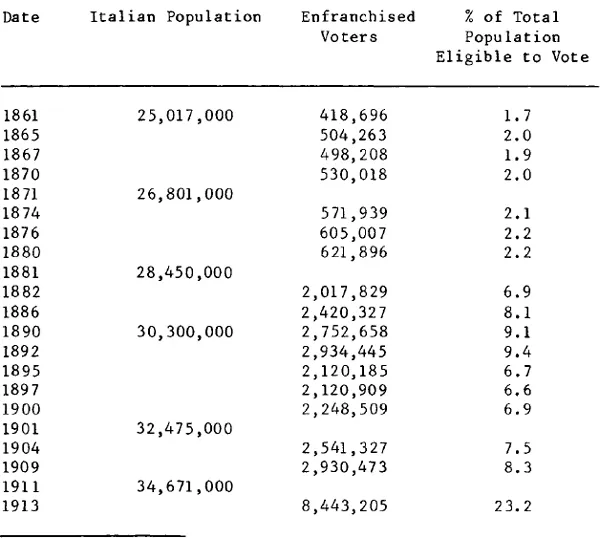

Uniquely among European countries, Italy from 1860 to 1912 required adult males to be literate and to pay a minimum direct tax in order to vote. The Italian system was somewhat mitigated by waiver of the tax payment requirement for those demonstrating a certain level of education, which in 1882 was lowered to four years of primary schooling. Before that year, only about 2 per cent of the Italian population could vote, and even afterwards the suffrage was restricted to less than 10 per cent of the citizenry (see Table 1.2). The literacy/education/tax-payment barrier proved especially pernicious in its discrimination against southern Italy, the poorest area of the country, which received little attention from the Italian government partly because so few of its inhabitants could cast ballots. Thus, in 1871, 46 per cent of all adults in northern Italy were literate, compared with only 16 per cent of adult southern Italians. Universal male suffrage was finally introduced in Italy in 1912.

Table 1.2 Suffrage Statistics for the Italian Lower Legislative Chamber, 1861–1913

Sources: Neufeld 1961: 524; Mitchell 1978: 5.

In addition to Italy, several other countries waived normal tax, income, or property requirements for those holding certain educational degrees or, in some cases, holding certain official positions and middle–class occupations. Norway was especially liberal in this regard, enfranchising after 1814 all government officials as well as citizens licensed as merchants and artisans. Spain after 1836 and Hungary after 1865 enfranchised a wide variety of persons following middle–class and professional occupations (known as capacidades in Spain and honoratiores in Hungary). Among those thus enfranchised in Hungary regardless of wealth were scholars, surgeons, artists, lawyers, engineers, teachers, and ministers. The attempt by these and several other countries to give extra weight to or at least to enfranchise all “responsible” citizens regardless of wealth—with the hope of thus eliminating from the ranks of the disaffected the most educated and articulate segments of the population, while still short–weighting or disenfranchising the rabble—gave rise to some electoral laws of staggering complexity. Thus, the Dutch electoral reform of 1896, which doubled the electorate by enfranchising 12 per cent of the population, provided that adult Dutch males could obtain the suffrage by: 1) paying one or more direct taxes at specified levels; 2) demonstrating they were householders or lodgers paying a minimum rent; 3) demonstrating they owned or rented boats of over 24 tons capacity; 4) demonstrating they earned an annual wage of about $115; 5) possessing a savings account of about $20 or owning about $40 in government bonds; or 6) passing a recognized examination qualifying for certain offices or employment or giving the right to work in specified professions. That even these seemingly liberal qualifications excluded about half of all Dutch male adults clearly demonstrated the poverty of the population.

A similarly convoluted franchise law introduced in Russia in 1907 led one American academic to conclude, “Even the educated man could not find his place in this complicated system; the uneducated man was quite lost” (Anderson and Anderson 1967: 336). The official Hungarian government organ conceded that Hungary’s 1874 electoral law—which reduced the suffrage from 900,000 to 700,000—was so complex that “the confusion of Babel has really been erected into law” (Seton-Watson 1934: 402). In 1912, there existed in the United Kingdom, according to electoral expert J. A. Pease, 11 distinct ways of qualifying for the franchise, with a total of 19 different variations altogether. Pease told the House of Commons in June 1912, “The intricacy of our franchise law is without parallel in the history of the civilized world” (Blewitt 1965: 30).

The most extraordinary class–biased suffrage systems in nineteenth–century Europe were those that gave extra votes to the wealthy and/or well educated (plural voting systems) or that separated citizens into voting categories by class criteria and extra–weighted upper-class votes (variously known as class, curial or estate voting systems). The Belgian plural voting system of 1893, in effect until equal and universal male suffrage was adopted in 1919 (along with limited female suffrage), enfranchised 1,354,891 Belgians (21 per cent of the population) compared with the previous tax–based system that gave the suffrage to 136,775. However, while all 25-year-old males were enfranchised in 1893, wealthy Belgians received a second vote. Those with a higher education, regardless of wealth, received two extra votes. No one could cast more than three votes. In 1893 under this system 850,000 Belgians had one vote; 290,000 voted twice; and 220,000 cast three votes. Thus, the 510,000 Belgians with plural votes, with a total of 1.24 million votes, could outpoll the remaining 850,000 Belgians. Plural voting was also allowed in the United Kingdom throughout the 1815–1914 period, in France between 1820 and 1830, in the lower two houses of the Swedish and Finnish diets (until 1866 and 1906, respectively), and in Russia between 1905 and 1907. Plural voting was also allowed on a trivial scale in Austria between 1861 and 1896, and on a wide scale there between 1896 and 1907.

About 7 per cent of the electorate in the United Kingdom—those meeting more than one franchise requirement or meeting property requirements in more than one constituency—cast plural votes in 1911, and in some cases individuals cast dozens of votes. Thus, the London Daily News of December 20, 1910, noted that a man “may own 20 small stables in 20 constituencies and he exercises 20 votes” (Blewitt 1965: 45). About 40 per cent of Austrian males cast two votes under the electoral system of 1896–1907. Under the French system of 1820–30, 90,000 Frenchmen elected 258 parliamentary deputies, while the richest 25 per cent of these electors cast a second vote and elected an additional 172 deputies.

Plural voting was defended by the same arguments used to justify other forms of class–based suffrage discrimination. Thus, Sir William Anson, a leading conservative constitutional lawyer, asked the British House of Commons in 1912, “Is the man who is too illiterate to read his ballot paper, who is too imprudent to support his children, to be placed on the same footing as the man who by industry and capacity has acquired a substantial interest in more than one constituency?” (Blewitt 1965: 45).

While plural voting systems explicitly and directly placed extra weight on the votes of the well-to-do and/or well educated, class, curial or estate voting systems did so indirectly by separating voters by class criteria into categories and assigning disproportionate numbers of legislative d...