![]()

1

Resisting Punitiveness in Europe? An Introduction

Sonja Snacken and Els Dumortier

1.1 Introduction

This book is both an end and a beginning. It is an end result of CRIMPREV, a Coordinated Action financed by the European Union under the 6th Framework Programme from 2006 to 2009, in which we organized a comparative seminar looking into factors enhancing or restraining primary and secondary criminalization in Europe. The seminar was organized in April 2007 at the start of the project. The authors of the different chapters in this book were also the original contributors to the seminar. Since that date, the field we were discussing has known significant developments. As such, this book participates in a broader movement which has developed over the last years aiming at understanding punitiveness and the mechanisms behind it by analysing both similarities (e.g. Garland 2001; Wacquant 2006) and national differences in punishment trends between countries (e.g. Tonry 2001, 2007; Whitman 2003; Cavadino and Dignan, 2006; Lacey 2008). The emphasis on ‘resistance’, however, indicates that this book wants to look at factors in those mechanisms that allow for choices to be made, primarily at the political and judicial levels. It attempts to do so within a ‘European’ context, in which ‘Europe’ is understood both in a comparative sense, looking at differences between European states, and in an institutional sense, looking at European institutions such as the Council of Europe or the European Union. We therefore do not claim to deal in this book with all the ‘risk and protective factors’ (Tonry 2007: 13-38) known to influence levels of punitiveness in different countries. This book wants to discuss a selection of what could be perceived as protective factors in a more horizontal, transnational way, trying to understand how these may – or may not or only partly – contribute to the aim of achieving more ‘penal moderation’ (Loader 2010) in Europe.

Hence the importance of the question mark in the title of the book. We do not claim that ‘Europe’ overall is resisting increased punitiveness, and there are many worrying developments to the contrary. We would rather argue that levels of punitiveness are related to such core values in European societies (and beyond) – social equality, human rights, democracy – that we should resist increasing punitiveness. This means, however, that we first have to explain what we understand by punitiveness and why we think it could be resisted at all.

1.2 The Concept of Punitiveness

‘Punitiveness’ is a complex, not always clearly defined concept. The ambivalence is already apparent in daily language. In the Oxford English Dictionary the adjective ‘punitive’ is explained both neutrally as ‘inflicted or intended as punishment’ (‘punitive measures’) and more quantitatively as ‘extremely high’ (‘punitive interest rates’). The same double meaning can be found in criminological literature. ‘Punitiveness’ refers in general to ‘attitudes towards punishment’ but is mostly understood as referring to ‘harsh’ (cf.Whitman’s Harsh Justice, 2003) versus ‘lenient’ or (better) ‘moderate’ attitudes to punishment (Loader 2010). The complexity doesn’t end here though. The concept of punitiveness refers to a wide variety of actors: to ‘popular’ attitudes towards punishment in the so called ‘public opinion’ or in the media, to political discourse, to primary criminalization by legislators, to decisions taken by practitioners within the criminal justice system (police, prosecution, sentencing, implementation of sentences, release procedures, etc.), or to attitudes of revenge or forgiveness of victims of crime.

‘Punitiveness’ also has a quantitative and a qualitative dimension. In the criminological literature of the last decennium, ‘punitiveness’ has mainly been studied with reference to forms of ‘increased’ or ‘new’ punitiveness in Western countries over the last 20 or 30 years (Garland 2001; Wacquant 2004; Pratt et al.2005; Kury 2008; Muncie 2008). Comparisons of levels of ‘punitiveness’ between countries or of historical developments in one particular country are often based on (trends in) the use of imprisonment. The most commonly used indicator is prisoner rates, i.e. the average number of prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants (i.e. ‘stock’). This is but an imperfect criterion, as it results from a combination of the incarceration rate (how many persons are incarcerated over a year: flow) and the length of stay in the prison, leaving the question unanswered whether countries who incarcerate less people but for longer sentences are more or less punitive than countries incarcerating more people but for much shorter sentences. Moreover, prison rates depend on what national authorities themselves define as ‘prison’. Juvenile custodial(-like) institutions, psychiatric units in prisons, asylums, etc. are not always taken into account. Pitts and Kuula (2005) have estimated that Finland via its youth welfare system may remove from home and institutionalize more children pro rata than do England and Wales. Such research reinforces concerns whether the concept of ‘punitiveness’ should only be measured with reference to rates of penal custody (Muncie 2008: 116). But ‘increased’ punitiveness also refers more qualitatively to a decline of rehabilitative ideals, harsher prison conditions, more emotional and expressive forms of punishment emphasizing shaming and degradation (e.g. chain gangs) or increased attention to victim’s rights as opposed to rights of offenders, etc. (Garland 2001). Examples of ‘new’ punitiveness are found in new forms of penal power which constitute a radical departure from previous trends in punishment, such as sexual predator laws which introduce civil commitment statutes, sex offender registration and notification schemes and mass incarceration (Brown 2005: 282–6) or the ‘adulteration’ of youth justice (Goldson and Muncie 2006: 199).

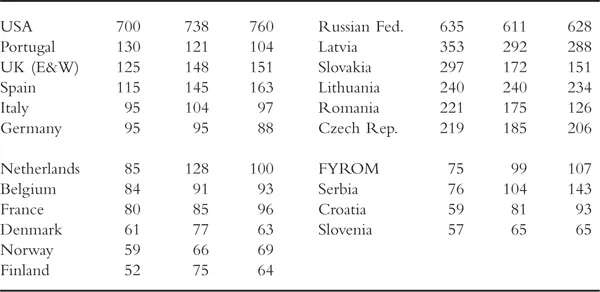

These increased or new forms of punitiveness do not tell the whole story though. The overall picture of punishment, more particularly in Europe, is much more diverse. Over the same period, the death penalty has been abolished on the whole European continent.1 Prison rates vary greatly, both in western and in eastern European countries (see Table 1.1). They have increased in several European countries, but have remained fairly stable (Scandinavian countries, Germany, Switzerland) or decreased in others (especially eastern European countries). Prisoners’ rights have been reinforced through the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) standards (van Zyl Smit and Snacken 2009). Restorative justice has gained political legitimacy in some countries as a valuable alternative to tackle victims’ rights and interests, even in the wake of horrendous crimes (Snacken 2007). All eastern European countries have now introduced non-custodial sanctions and measures (van Kalmthout and Durnescu 2008) and treatment programmes for offenders are (re-)introduced by ‘what works’ evidence-based penal policies in many western and eastern European countries (Canton 2009; Bauwens and Snacken 2010). In many continental European countries the traditional ‘welfare’ approach to juvenile offenders remains strong and is still reflected in legislation emphasizing ‘protection measures’ (Junger-Tas 2006: 515; Dünkel et al.2010).

Table 1.1 National differences: prison population rates USA and Europe 2000–2005–2008

Source: World Prison Brief (ICPS 2010).

Furthermore, how should we assess the level of punitiveness of all forms of penal interventions? Indeed, non-custodial sanctions, restorative justice or treatment programmes can also be ‘punitive’, measured by their interference in the fundamental rights and freedoms of offenders. For an illustration, see Barbara Hudson’s (2006) analysis of the latter two forms of penal interventions into the privacy and the ‘secrets of the self’ of offenders. Or see the criticisms on an unfettered welfare (Van de Kerchove 1977: 246) or restorative justice (Eliaerts and Dumortier 2002; Dumortier 2003) approach to juvenile delinquents, which may mask punitive practices while downplaying due process guarantees. Non-custodial sanctions vary in the number of obligations imposed, the level of control and surveillance involved and the stigma resulting from the imposition or implementation. ‘Intermediate sanctions’ have been introduced in many countries with the explicit aim of being more controlling and punitive than normal probation but less so than prison (Byrne et al.1992). Or to be ‘more burdensome and restrictive’, as described by Tonry and Hamilton (1995: 15). If their application results in pure net-widening, the level of punitiveness increases. If they really replace imprisonment, the level of punitiveness could be said to decrease, at least if they impose less restrictions and control than imprisonment.2

It is impossible to deal with all these complexities in this book. We do cover, however, both quantitative and qualitative dimensions of punitiveness. Prisoner rates are used in Chapters 2 and 3 as the basis for comparisons between different countries and the search for possible explanations. Quantitative and qualitative dimensions of punitiveness are illustrated in Chapters 6 to 8 with reference to the impact of human rights standards on (limits to) criminalization and on the (qualitative) treatment of prisoners and in Chapters 9 to 12 on the possible impact of the increased attention to victims of crime and ‘public opinion’. We also look at different actors involved in determining levels of punitiveness and their interactions: policy-makers, judiciary, victims, members of the public.

1.3 Explaining Trends in Punitiveness – Possibilities for Resistance?

1.3.1 Global Trends Versus National Differences

Recent studies into explanations of trends in punitiveness reflect diverging approaches. One approach emphasizes social and political changes common to all western societies which are described as influencing their criminal justice systems in similar more punitive directions. Garland’s (2001) analysis of the US and the UK as two late-modern, high-crime societies, in which an angry and anxious public has led politicians to resort to punitive policies of exclusion, or Wacquant’s (2004, 2006) study of the neo-liberal transformation of western welfare states into penal states, are illustrations of this approach. Another approach stresses and attempts to explain different developments in individual jurisdictions (Tonry 2001; Cavadino and Dignan 2006). A third approach looks at both convergences and diversity emerging from such comparisons and analyses not only risk but also protective factors for increased punitiveness (Goldson and Muncie 2006; Tonry 2007; Lappi-Seppälä 2007, 2008; Lacey 2008).

Whatever the approach, the question of possibilities of resistance against increased punitiveness is dependent on two conditions: first, that the factors explaining trends in punitiveness within one country or between different countries leave some possibilities of (political) choices; second, that these possibilities of choices are not linked to ‘ontological’ or historical characteristics of the nations concerned which make them not transferable to other jurisdictions. Both aspects have been the subject of quite some debate.

1.3.2 The (Relative) Importance of Political Decision-making

Garland’s (2001) analysis of the emergence of a new ‘culture of control’ in the UK and the US has sparked interesting debates on this issue. His emphasis on the totality of the field of crime control rather than on ‘penality’ alone allowed him to focus on and to explain the increased importance of non-state reactions to crime and insecurity: ‘the biggest change had been the shifting place of crime in our daily lives, our built environment, and our cultural imagination [...], the emerging tendency towards the breakup of the state’s supposed monopoly of crime control [...], the shift from law enforcement to security management’ (Garland 2004: 170). The result, however, has been criticized for creating a ‘bleak’ or ‘dystopian’ outlook (Zedner 2002) or a ‘criminology of catastrophe’ in which politics seems ‘epiphenomenal’ (Loader and Sparks 2004: 15–16). Garland refutes these arguments, but also warns against focusing too much on politicians as ‘the usual suspects’ (Garland 2004: 185). At the end of Culture of Control, he stresses that the current configuration of crime control and criminal justice in the UK and the US ‘is the [...] outcome of political and cultural and policy choices – choices that could have been different and that can still be rethought and reversed’ (Garland 2001: 201). He also acknowledges that ‘while in the UK and the US political decisions have stressed exclusion and punitive measures, other countries may choose differently’ (Garland 2001: 202). The possibilities of choices may even be enhanced now, as ‘a field in transition makes it more open than usual to external forces and political pressures. Hence this is a historical moment that invites transformative action [...] precisely because it has a greater than usual probability of having an impact’ (Garland 2001: 25). On the other hand, he qualifies the possibility of political choices, contending that they must resonate with political, popular and professional cultures emerging in the same period:

But it is possible to overestimate the scope for political action, and to overestimate the degree of choice that is realistically available to governmental and non-governmental actors. And it is all too easy to forget the extent to which political actors are, in their turn, acted upon. (Garland 2004: 181)

I do not consider politics to be merely epiphenomenal [...] The political is clearly a crucial level with its own dynamics, contingencies and dispositive effects. But nor do I consider it to be an unconditioned domain. Indeed a primary concern of the Culture of Control is to identify the social, economic, cultural and criminological circumstances that constrain and enable political action. (Ibid.: 187)

As far as these criminological circumstances are concerned, he acknowledges that his focus on the shifts in ‘official criminology’, showing ‘the emergence of new criminological rationales that came to dominate governmental practices and the reasons why these were preferred to the social welfare criminologies that previously prevailed’, tends ‘to misrepresent the real nature of the field’ and to disregard the continued ‘cultural capital and prestige’ of critical and sociological criminology, even if it has lost political power (in the UK and the US). It is precisely ‘the continuing force of these competing actors and discourses’ that gives ‘sociological substance’ to the claim that choices can still be rethought and reversed (Garland 2004: 167-8).

This is exactly what this book aims for. Other case studies of penal policies and their ensuing ‘scales of imprisonment’ have demonstrated that, although they result from a complex interaction of different factors, they are – or can be – at least partly influenced by political decision-making (Rutherford 1984; Zimring and Hawkins 1991; Snacken et al.1995; Snacken 2007; Goldson 2010). Some of these factors lie outside the criminal justice system (‘external factors’), such as demographical changes (age structure, immigration) and economic trends. Others refer to attitudes and decisions made within the criminal justice system (‘internal factors’) or to factors at least partly influenced by the criminal justice system (‘criminality’ as defined and tackled by the system). A third category (‘intermediate factors’) refers to the interaction between penal policies and public opinion, the media and the po...