![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Three-Stratum Theory of Intelligence: Spearman’s Contribution

John B. Carroll

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

It is most gratifying to have been accorded the status of “the Spearman lecturer” in the first of a projected series of seminars concerned with intellectual abilities. I hope that the thoughts I express in this chapter are not considered in any way to devalue or detract from the enormous contribution of Charles Spearman to the study of intelligence. Spearman, after all, laid the groundwork for practically every research endeavor in this domain from his time up to the present, and his influence will certainly continue to be felt for a long time into the future. I find myself in agreement with much of Spearman’s thinking, as expressed in his various works such as The Nature of Intelligence and the Principles of Cognition (1923) and The Abilities of Man: Their Nature and Measurement (1927). Where I (or anyone) could justifiably differ with him consists chiefly in matters that have become clearer through the research of the past seven decades, that has been accomplished with more precise and comprehensive methods than were available to him. Even so, it is remarkable how much our present-day theories and methods rely on principles and procedures that he established during his lifetime. Although some discussions might suggest that his ideas were challenged in fundamental ways by subsequent investigators such as L. L. Thurstone, P. E. Vernon, R. B. Cattell, and J. P. Guilford, it now appears that these later investigators merely refined and elaborated Spearman’s views, in some ways for the better, and in some ways, I think, for the worse.

A THREE-STRATUM THEORY OF COGNITIVE ABILITIES

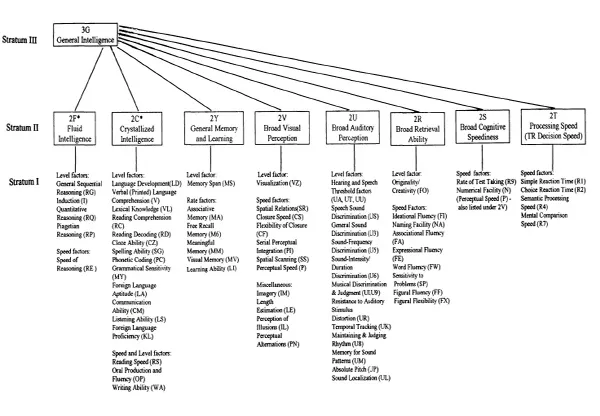

These, at any rate, are the thoughts that I have come to hold as a result of a thorough review of factor-analytic studies of cognitive abilities that I have made in the past few years, summarized in a book, Human Cognitive Abilities (Carroll, 1993). What I developed in that survey was what I call a three-stratum theory that depicts the total domain of intellectual abilities in terms of three levels or strata (see Fig. 1.1).

At the top stands a single factor at Stratum III, identified as 3G, General Intelligence, conceptually equivalent to Spearman’s g. Obviously, Spearman’s g is his major contribution to a theory of cognitive abilities.

Following, there appear eight broad factors at Stratum II, including 2F (or Gf), Fluid Intelligence, 2C (or Gc), Crystallized Intelligence, and several other broad factors of ability. Lines connect the Stratum III General Intelligence factor with Stratum II abilities to suggest that the g factor dominates the Stratum II abilities to varying extents. That is, phenotypic measurements of the second-stratum abilities are likely to be correlated with phenotypic measurements of g to greater or lesser extents. The relative sizes of these correlations are suggested by the relative nearness of a Stratum II factor to the Stratum III general factor. For example, Factor 2F, Fluid Intelligence, appears to be more highly related to g than Factor 2T, Processing Speed, if the latter relation is in fact other than zero. Later I discuss the question of whether Fluid Intelligence is to be taken to be identical to g, as postulated by some writers.

Finally, it appears that each of the Stratum II factors dominates a series of “narrow” factors assigned to Stratum I. In Fig. 1.1, I have listed a number of such factors under each of the Stratum II factors. Ordinarily such factors appear at the first order of analysis; some of them, for example, are Thurstone’s “primary” factors.

It is pertinent at this point to mention that all factors can appear in either of two forms, depending on the nature of the matrices that contain loadings of variables on factors or loadings of factors on higher order factors. What may be called phenotypic factors are generally oblique to each other, in the sense that they are correlated with each other. Loadings on such factors are shown in either reference vector or pattern matrices, and the correlations among such factors are shown in higher order correlation matrices. In contrast, what may be called genotypic factors are orthogonal to each other because their covariance with factors at other orders has in effect been partialed out. It follows that the correlations among such factors are zero. Loadings on such factors are shown in hierarchical factor matrices produced by the Schmid–Leiman orthogonalization procedure (Schmid & Leiman, 1957). I am not sure that genotypic is the best word for characterizing such factors; I use it mainly because it contrasts to phenotypic, which seems to characterize a factor that would be manifested in scores directly derived from test scores by any of several procedures discussed in treatises on factor analysis, and would thus contain variance from factors at different orders. For example, a score on a phenotypic factor could contain variance from a general factor, a second-stratum factor, and a first-stratum factor. A score on a genotypic factor, on the other hand, would constitute an estimate of a person’s score on that factor, with variance from other strata partialed out. I find it useful to note loadings of variables on orthogonal genotypic factors, which show the extent to which they contain variances independent from genotypic factors at different strata. To my mind, genotypic factors represent latent causal elements in test scores. For example, in interpreting data in a hierarchical factor matrix, a variable with a loading of .6 on a general factor, .5 on a fluid intelligence factor at Stratum II, a loading of .4 on a Stratum I verbal factor and a loading of .3 on a Stratum I induction factor, could be assumed to be independently influenced by each of those factors, to the extent indicated by the loadings.

* In many analyses, factors 2F and 2C cannot be distinguished: they are represented, however, by a factor designated 2H, a combination of 2F and 2C.

FIG. 1.1. The structure of cognitive abilities (from Carroll, 1993. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press).

Considering that Fig. 1.1 represents a structure of correlated factors, it represents phenotypic factors. Underlying it, at another level of presentation, so to speak, one can assume a structure of orthogonal genotypic factors that differ principally in their generality over the domain of cognitive abilities. The g factor is most general, second-stratum factors are less general, and first-stratum factors are least general. Actually one can envisage a structure in which all factors are orthogonal, differing only in their degree of generality. This type of structure is in fact represented in the “nested” designs postulated by Gustafsson and Undheim (1992) and specified in orthogonal factor matrices input to confirmatory analyses. My use of stratum arises from my methodological preference for exploratory factor analysis as an initial heuristic procedure.

For this and other reasons, the structure presented in Fig. 1.1, therefore, should not be taken too literally or precisely. It is only a conceptually ideal structure suggested by the total array of data that I have analyzed—more than 460 datasets found in the factorial literature. My approach is analogous to what has been called “meta-analysis” in other fields of psychological and educational research, in the sense that it attempts to establish or estimate the “true” structure of intellectual abilities that would be revealed if one were able to use an infinite set of ideal measures in factor analysis. In practice, the third-stratum g factor does not always show up in the analysis of a particular dataset, and often, second-stratum factors either do not appear or cannot be distinguished from one another. Furthermore, the Stratum I factors appearing for a particular dataset are not always related to Stratum II factors in the manner suggested by Fig. 1.1. Either they are related to different Stratum II factors from those indicated in Fig. 1.1, or they may be related to two or more such factors. These complications are undoubtedly the result of the design of particular datasets—that is, the variables that were chosen to be included in the dataset, not all the variables being adequately “pure” in a factorial sense, and the variables not being chosen to cover all the possible domains of cognitive ability. It is for this reason that I would urge that factor-analytic research needs to be greatly expanded and refined in order to approximate more closely the true structure of cognitive abilities, to the extent that factor analysis could make such an approximation possible. Expansion would come from the inclusion of a greater variety of variables over the postulated domains of ability, and refinement would come from more focused work on the manner in which ability constructs are measured—possibly through the greater use of item response theory and applications of basic measurement theory.

From this perspective, Spearman’s work can be viewed as contributing a glorious and honorable first approximation to the true structure of cognitive abilities—an approximation that in many ways has stood the test of time, but that contrarily, has over the years since then been shown to be grossly inadequate. Spearman cannot be faulted for being unable to go much beyond his first approximation. Going beyond what he established has required decades of further research, and even now we have only perhaps a second or third approximation.

GROUP AND SPECIFIC FACTORS

It is pertinent to inquire just how far Spearman’s glorious approximation went in achieving the kind of structure suggested in Fig. 1.1. In The Abilities of Man, we find considerable discussion of what Spearman called “group factors,” attributed by him to “overlap between specific factors” (pp. 79–82). A series of chapters in Part II was devoted to various possible special abilities and group factors of this sort. But Spearman was at all times skeptical about them. “They make their appearance here, there, everywhere; the very Puck of psychology,” he wrote. “On all sides contentiously advocated, hardly one of them has received so much as a description, far less any serious investigation” (p. 222). Almost grudgingly, Spearman acknowledges the existence of “a very large additional factor common to the tests of Reasoning and of Generalization” (pp. 225–226). “Here then,” he wrote, “we appear to have discovered a ‘special ability’ or group factor, broad enough to include a sphere of mental operations that is very valuable for many purposes in ordinary life. Quite possibly, indeed, this special logical ability may not be innate, but acquired by training or habit. Even so, its importance would not lose in degree, but would only shift from the region of aptitude to that of education.” Would this “group factor” be what R. B. Cattell later recognized as Gf, fluid intelligence? Or would the “spatial cognition” factor that Spearman recognized (p. 229) in the work of McFarlane (1925) be the Space factor identified later by Thurstone (1938)? Similarly, could we not cross-identify a group factor of arithmetical abilities that Spearman (p. 230) recognized in the work of Collar (1920) with the N (Numerical Facility) factor of Thurstone and many other investigators? It is unfortunate, in a way, that Spearman could not properly appraise various results that he discussed in this chapter on special abilities. He was limited to use of his tetrad equation in evaluating these findings. His final comment in the chapter was as follows:

The main upshot of this chapter is negative. Cases of specific correlations have been astonishingly rare. Over and over again, they have proved to be absent even in circumstances when they would most confidently have been anticipated by the nowadays prevalent a priori “job analysis.”

Among the exceptional cases where, on the contrary, specific correlations and group factors do become of appreciable magnitude, the four most important have been in respect of what may be called the logical, the mechanical, the psychological, and the arithmetical abilities. In each of these a group factor has been discovered of sufficient breadth and degree to possess serious practical consequences, educational, industrial, and vocational.

The same may be said of yet another important special ability which was reluctantly omitted from our preceding account for want of space; this is the ability to appreciate music. (pp. 241–242)

I will not take time to refer to further instances of Spearman’s recognition, in The Abilities of Man, of possibly important group factors beyond g, including, for example, a group factor of “retentivity” that is possibly similar to Memory factors identified by Thurstone and others. Instead, I turn to the volume by Spearman and Wynn Jones (1950), for more evidence of the extent to which Spearman admitted the existence of group factors. From the preface to this volume, one learns that it was in the main jointly written by Spearman and Wynn Jones beginning in 1942 and ending in 1945, when Spearman died. Thus it may be taken as Spearman’s final statement on the structure of cognitive abilities. Nevertheless, it is evident that probably due to delayed circulation of scientific writings in the war years, the volume was very limited in its reference to studies published in the United States after about 1940.

In Chapter II of this book we find the following statement: “As regards the statistical results of this method (of factorizing), these have only been outlined. They have consisted of (1) a general factor; (2) an unlimited number of narrow specific factors; and (3) very few broad group factors” (p. 15).

The casual reader might interpret this passage as almost an exact description of a three-stratum theory of cognitive abilities. Such an interpretation, however, would not be quite correct. To be sure, the general factor forms the third stratum of the theory, and the “broad group factors” form the second stratum. But in speaking of “an unlimited number of narrow specific factors” Spearman seemed to have in mind not necessarily the narrow first-stratum factors of the theory, but rather, the specifics that can be associated with particular variables. Spearman and Wynn Jones recognized that the term specific factor has had “at least three different versions,” namely:

(a) As used originally by the senior writer: that is to say, the whole content of any ability other than its general part.

(b) The non-recurrent part; that is to say, the part of any ability which does not recur in any other of any given set of abilities.

(c) Any ability content which cannot recur in any other ability whatever. (p. 77)

On the whole, it is exceedingly difficult to interpret Spearman and Wynn Jones’ discourse about specific factors without translating it into a discourse using s in the sense defined by later writers, including Thurstone, as an ability that is independent of any error, but also independent of any common factor identified in a particular set of ability measurements. Such a definition recognizes, as did Spearman, that what may be a specific factor in a particular battery may become a common factor in a second battery if such a specific factor is measured by more than one variable in the second battery.

Subsequent chapters of this book discuss various “broad factors” that Spearman and Wynn Jones recognized, though with much caution. They were aware of Thurstone’s study of primary abilities as published in 1938, and of Holzinger’s studies (e.g., Holzinger & Swineford, 1939) conducted in the “Unitary Trait” program of researches. Among the broad factors treated were a Verbal factor (Chapter XI), a Mechanical factor (Chapter XII), and Arithmetical, Fluency, Psychological, and Retentivity factors (Chapters XIII, XV, XVII). From a present-day perspective, one might say that Spearman and Wynn Jones were limited both by inadequate methodology and by an inadequate amount of experimental evidence that they were able to consider. But if they had not been limited in these respects, I would not think that they would be opposed to a three-stratum theory. A three-stratum theory, at least, tends to fit the evidence they had at hand.

Nowadays the conventional wisdom is that the general factor is by far more important than lower-stratum factors. Possibly Spearman’s emphasis on the importance of the general factor has been responsible for this “conventional wisdom,” but it has also resulted from the frequent finding that lower-stratum factors seldom add much predictive validity to what can be obtained from measures of the general factor. I believe that the conventional wisdom is to some extent incorrect, however, because there are many types of learning or performance that can be shown to depend not only on the general factor but also on lower-stratum...