![]()

1

What We Do When Things Go Wrong

Charles F. Hermann

This is a book about managing foreign and security policy in cases of protracted decision making. More specifically, the contributors address the difficult – but common – situation in which a government commits to a major course of international action only to discover later that it is not working as planned. In the face of feedback that a major policy is failing, do policy makers stay the course or change direction? Everyone recognizes that the overwhelming tendency is to remain steadfast. Mythology often celebrates those who persevere with the belief that it is “darkest just before the dawn” and praise those resolute actors who refuse “to change horses in midstream.” Such stalwarts are celebrated as prevailing against the odds like a heroic Horatio Alger.

Yet at times we recognize that in retrospect it was foolhardy to persist in continuing in a failed direction. Indeed, recognizing that a given solution is ineffective or totally wrong can be one of the important circumstances for learning. And so, we also celebrate those people and organizations that correctly buck the temptation to continue on a failing path.

Whatever the judgment one holds about the merits of the American-led invasion of Iraq beginning in March 2003, the scale and violence of the subsequent Iraqi insurgency was unanticipated by Bush Administration. American forces, their coalition partners, and the evolving Iraqi military were unable to provide physical security in most areas of the country. Indications of failure were widespread. When Colin Powell met President George W. Bush a final time as the general stepped down as Secretary of State in January 2005, Powell allegedly said bluntly:

If, by April, the situation there [in Iraq] had not improved significantly, the president would need a new strategy and new people to implement it. Bush looked taken aback: No one ever spoke this way in the Oval Office. But because it was the last time, Powell ignored every cue of displeasure and kept going until he had said what he had to say.

(Packer, 2006: 445)

It took President Bush and his top advisors several more years before he implemented the kind of change Powell candidly advised. Noteworthy, however, is that elements in the United States Army did recognize problems early on with the Iraq strategy and began to press for change.

Many observers who have followed the Iraq War recognize the persistent critique offered by Lt. Col. John A. Nagi (ret), Colonel H. R. McMaster (later promoted to brigadier general) and others who led combat units in Iraq and studied counter insurgency. Consider, as another example, General Casey’s consent in the summer of 2005 to permit his aide, Colonel Bill Hix, and a retired Special Forces officer, Kalev Sepp, to survey 31 military units and their field commanders on their counterinsurgency effectiveness. They filed a devastating report. In the near term, that report triggered only limited action that General Casey could introduce on his own (i.e., training for incoming officers in counterinsurgency principles). The critiques persisted, however, and gained attention both inside and outside the military. In 2006, Congress appointed an Iraq Study Group consisting of former top-level government officials and recognized experts, including Robert Gates who soon replaced Donald Rumsfeld as Secretary of Defense. They heard from General Peter Chiarelli, then commander of the Multi-National Corps–Iraq, who spelled out the problems in detail, noting that something more than killing the bad guys was needed and that protecting and improving the quality of life of civilian Iraqis was a missing imperative (Cloud and Jaffe, 2009: Chapter 11).

It is not uncommon for some military officers charged with responsibility for executing particular strategies or tactics to recognize signs of failure. The same occurs in a similar fashion in many organizations. What is noteworthy is that the critiques were made repeatedly to superiors and that some listened. Over time, advocates for a change in the military approach to the war in Iraq prevailed in policy … making circles. Early in 2007, General David Petraeus assumed command in Iraq committed to implementing a new strategy. Columnist David Brooks captured the transformation in an article in the New York Times:

Five years ago, the United States Army was one sort of organization, with a certain mentality. Today, it is a different organization, with a different mentality. It has been transformed in the virtual flash of an eye, and the story of that transformation is fascinating for anybody interested in the flow of ideas… The transformation began amid failure. The U.S. was getting beaten in Iraq in 2004 and 2005.

(Brooks, 2010: A27)

Some will contend that the change to an extraordinarily costly policy took too long to occur. Others may argue that it was incorrect to change the strategy rather than the policy goal. No attempt will be made here to reconstruct the complex sequence leading ultimately to a change in Iraq strategy. Suffice it to note that ultimately change did occur. But the case does highlight critical questions that concern the contributors to this book. Under what conditions are individuals or groups likely to change policy? If they initiate any change, what determines the kind of change undertaken?

A Pervasive Human Dilemma

What should we do when something in which we personally have invested both substantial effort and resources appears to be performing poorly? A person purchases new tires for their old car thinking that it otherwise is in reasonable condition. Suddenly a major leak requires replacement of the radiator. A company invests substantially in upgrading one of its retail outlet stores, but following the reopening sales continue significantly lower than expectations. A wife has been physically abused by her husband to whom she has been devoted. He pleads for forgiveness and promises never to hit her again, but then there is another incident followed immediately by more impassioned promises. Should the car owner sell the clunker or replace the radiator? Should the company give up on the store or launch a major sales promotion? Should the wife leave her husband or give him another chance? Similar challenges occur at every level of human experience – from the individual to the society. In various forms the generic issue is: stay the course or change direction? Of course, equivalent choice dilemmas occur regularly in politics and foreign policy as well. Whether the United States should continue in Afghanistan is a stressful example for Americans and many others elsewhere. It is noteworthy that at almost every level, when the prior commitment to the existing course of action has been substantial, we are predisposed to continue.

As we shall see, analysts have offered psychological and organizational explanations for this tendency to continue despite warnings of possible failure. To the aggregation of explanatory forces from other areas of human endeavor, we must add yet other factors when we enter the political realm. In all political systems there is competition for the exercise of power. Sometimes opposition is latent and secretive, as often occurs in a dictatorship or an authoritarian system. In more democratic societies, opposition appears more open and explicit. Whether latent or open, potentially every leader faces opposition.

At the outset of their innovative theory of comparative political office-seeking, Bueno de Mesquita and his colleagues note what many view as a fundamental of political life:

Our starting point is that every political leader faces the challenge of how to hold onto his or her job. The politics behind survival in office is, we believe, the essence of politics. The desire to survive motivates the selection of policies and the allocation of benefits; it shapes the selection of political institutions and the objectives of foreign policy; it influences the very evolution of political life.

(Bueno de Mesquita et al., 2003: 8–9)

In short, a near universal motivation of policy makers in power is to retain office. As the authors above note, policy becomes a vital instrument for maintaining their position.1 For a political leader, or any set of high level public office-holders, to acknowledge the failure of any of their policies opens them to their greatest danger – attack by opposition and possible loss of office. In authoritarian systems, where opposition may be hidden, overthrow of the existing regime may mean poverty, humiliation, exile, or death. Of course, the arena of political decision making that can affect office holding includes the domain of immediate concern – foreign policy.

A change in direction in foreign policy – or any other area of public policy – is a fundamental challenge for any government whether authoritarian or democratic. Pressures for continuation often seem overwhelming. For many policies and numerous situations, the significant change may seem limited to shifts in power when new people or regimes take control. More limited adjustments to policy within the same regime, however, are not that uncommon. The George W. Bush Administration’s approach to dealing with the nuclear programs of North Korea was substantially revised when earlier initiatives failed to achieve the desired results. Even major changes in policy occasionally transpire. F. W. de Klerk released Nelson Mandela from prison and then negotiated with him and his associates to end apartheid in South Africa. Anwar Sadat of Egypt abandoned a policy of aggression against Israel and went to Jerusalem. Mao Zedong gave up on the Great Leap Forward. Lyndon Johnson eventually decided further deployments of American ground forces in Vietnam would do no good. Understanding when governments change their policies and whether they make minor adjustments or major shifts is an important challenge. Not all changes in policy reflect learning. Certainly a better understanding of policy changes, however, enables us to explore the question: Under what conditions do policy makers learn?2

Sequential Decision Making in Foreign Policy

Many foreign policy issues require repeated attention from the individuals or organizations responsible for their management. Rarely does a policy issue of any consequence surface once, receive attention from the responsible policy makers and then disappear, never to require further consideration. Far more common are issues with a protracted life that demand repeated processing through time. In some instances, this sequential decision making is planned from the outset with the expectation that a progression will transpire that will pose subsequent choices. Participants in international negotiations, for example, usually know they will be involved in an iterative process often extending over considerable time.

Another class of sequential problems emerges not from an acknowledged continuing process or an established routine, but rather from issues that resurface repeatedly because prior initiatives appear not to have managed the problem satisfactorily or not completely. They are difficult, thorny problems that require consideration again and again. It is this class of sequential decision-making problems that this book addresses. The question is how will policy makers adjust their prior action when confronted with reports that their previous initiative is not having the desired effect or, at least, appears insufficient? More specifically, we ask when will policy makers change direction? (See Hermann, 1990.) When will they dig in their heels and stay the course rather than break off the existing approach and begin anew?

Sequential decision making occurs when one or more policy makers engage in a series of decisions about the same issue or problem area across a period of time. An issue area is a recognized domain involving interests or values of the decision makers. In an initial occasion for decision a problem is recognized within that issue area and, after deliberation, the first decisions are made (to take certain actions or to do nothing). Following these initial decisions, a momentary sense of closure is reached for the decision makers, and they typically turn their attention to other matters.

The decision making becomes sequential when the policy makers subsequently find that they must reconsider the problem or some variant of it. Some problems are considered repeatedly over a period of months or years. The result is a sequence of “N” occasions for decision with respect to a single problem or a series of highly interrelated problems.

It should be apparent that policy change, if it occurs, takes place in the context of a stream or sequence of policy decisions. At some point decisions are taken to pursue a particular course or to move in a specific direction with respect to some goals. Subsequently, the policy makers have occasion to reconsider their previous commitments. Then the issue is whether they continue their prior course or modify the previous decisions.

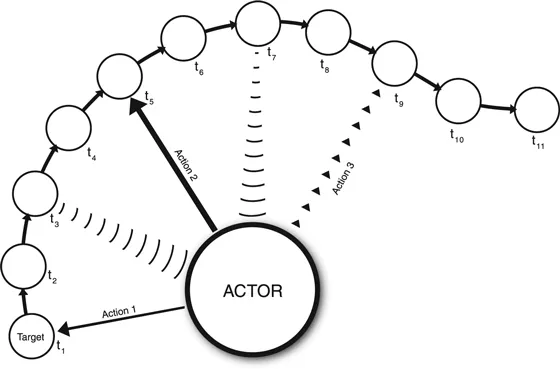

Figure 1.1 offers a representation of this process with an actor directing some action toward a target entity at time1 intending to affect the target’s behavior (illustrated in Figure 1.1 as the direction of the target’s movement).

As shown, however, the target continues along its unaltered trajectory at time2, and again at time3. By this time the actor recognizes some feedback indicating its effort to change the target’s course has not produced the desired result. (Feedback in Figure 1.1 appears as a wave of partial circles emanating from the target toward the actor.) The actor then decides to initiate similar but stronger action at time5. Still the target’s path remains unchanged at time6 and time7. Figure 1.1 depicts that in response to further feedback received at time7 the actor attempts a different kind of action, which appears to be changing the direction of the target at time11. Figure 1.1 seeks to illustrate several essential points in sequential decision making. First, of course, is that the problem management occurs intermittently across time. Second, how much time elapses between iterative decisions depends on signals or feedback, how quickly the actor recognizes the signals and how it elects to interpret the new information. In any case, lags between iterative decisions are inevitable. Finally, the figure underscores the human tendency to respond – for some time – to negative feedback with continuation of the same kind of action only with greater investment.

Figure 1.1 Sequential actions by actor intending to change target’s behavior

Our concern here is with factors affecting the Nth consideration of a problem by the same decision makers. The core assumption underlying this analysis is that the problem solving...