eBook - ePub

Wretched Kush

Ethnic Identities and Boundries in Egypt's Nubian Empire

Stuart Tyson Smith

This is a test

Share book

- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wretched Kush

Ethnic Identities and Boundries in Egypt's Nubian Empire

Stuart Tyson Smith

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Professor Smith uses Nubia as a case study to explore the nature of ethnic identity. Recent research suggests that ethnic boundaries are permeable, and that ethnic identities are overlapping. This is particularly true when cultures come into direct contact, as with the Egyptian conquest of Nubia in the second millennium BC.

By using the tools of anthropology, Smith examines the Ancient Egyptian construction of ethnic identities with its stark contrast between civilized Egyptians and barbaric foreigners - those who made up the 'Wretched Kush' of the title.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Wretched Kush an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Wretched Kush by Stuart Tyson Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Boundaries and ethnicity

A coward is he who is driven from his border.

Since the Nubian listens to rumors,

To answer him is to make him retreat.

Attack him, he will turn his back,

Retreat, he will start attacking.

They are not people one respects,

They are wretches, craven hearted.

My Majesty has seen it, it is not an untruth.

King Senwosret III, c. 1850 BC

Since the Nubian listens to rumors,

To answer him is to make him retreat.

Attack him, he will turn his back,

Retreat, he will start attacking.

They are not people one respects,

They are wretches, craven hearted.

My Majesty has seen it, it is not an untruth.

King Senwosret III, c. 1850 BC

(Lichtheim 1973: 119)

Modern boundaries seem firm and immutable. National borders are delineated through diplomatically recognized maps and on the ground through border posts, customs offices and physical barriers. Travel across them is regulated by treaty and enforced by bureaucrats, military, and police. Although sometimes disputed, arguments over boundaries concern where to draw the line, not whether the line should exist at all. Even when different polities are unified, as with the European Union or the former Yugoslavia, internal boundaries have proven surprisingly resilient (e.g. Darian-Smith 1999; Jones and Graves-Brown 1996). In a similar way, ethnic groups are seen as bounded, distinctive entities. Ethnic identity is based upon a real or perceived (self-defined) shared culture, history, and language. Ethnicity can also be ascribed by others, a phenomenon that is particularly common in colonial contexts like the one discussed here. As the quote above illustrates, Egyptian ideological stereotypes presented Nubian ethnicity in negative terms, in this case as cowards. In the celebratory monuments of the ancient Egyptian state, Nubia could not simply be referred to by its ancient name, Kush, but must always be “Wretched Kush.” The negative qualities of Nubian ethnicity helped to define the positive qualities of Egyptian-ness. Both of these perspectives, internal and external, represent ethnic groups as distinctive traditions, bounded in space and time. In a similar way, the archaeological search for national and ethnic boundaries has typically assumed that distinct transitions between groups and polities will be manifested in the archaeological record. Recent investigations suggest, however, that this view is too limiting. Boundaries are and were more permeable than the pronouncements of governments assert (e.g. Driessen 1992). There is also an emerging consensus that ethnic identities are not absolute and bounded, but rather situational and overlapping.

This is particularly true when cultures come into direct contact, like the Egyptian conquest of Nubia that forms the focus for this volume. Most studies of ethnicity and imperialism have understandably focused on the groups dominated by empires, often emphasizing the role of ethnic identity in the assimilation or resistance of native groups. In the past, culture contact tended to be regarded using “quincenten-nial” models emphasizing the unequal relations of Old World dominance over New World cultures. Cultural influence was, and often still is, assumed to be unidirectional. In particular, acculturation models stressed a European donor culture transforming a passive Native American culture into an image of the dominant core (Foster 1960; Spicer 1962). Acculturation models like this one continue to be used today, sometimes in surprising contexts like the spread of agriculture in Neolithic Europe (eg. the Demic Diffusion model of Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza 1984; Cavalli-Sforza 1996), or the replacement of Neanderthals by modern humans (D’Errico et al. 1998).

Cultural changes resulting from contact are, however, neither inevitable nor unidirectional, as Malinowski (1945: 12) asserted, simply “the result of an impact of a higher, active culture on a simpler, more passive one.” Recent anthropological publications have re-evaluated culture contact studies, abandoning this simplistic view of acculturation (Curtin 1984; Thomas 1990; Schortman and Urban 1992; Wilson and Rogers 1993; Lightfoot 1995; Cusick 1998; Stein 1999). Instead, these scholars focus on a more complex constellation of contact situations with varying degrees of incorporation, transformation and rejection as opposed to straightforward assimilation (e.g. Bishop 1984; Dietler 1990; Helms 1992; Rogers 1990; Stern 1982; Wells 1992; Jones 1997; Deagan 1998; Smith 1998). Native American responses to European colonialism are therefore now seen as complex adaptations, transculturation or ethnogenesis rather than acculturation (Charlton and Fournier G. 1993; Cleland 1993; Rogers 1990; 1993; Farnsworth 1992; Turnbaugh 1993; Waselkov 1993). For example, as Bamforth (1993) has demonstrated, even the adoption of metal tools in California was conditioned by a complex set of factors, including cultural considerations as well as the effectiveness of the new technology. Indeed, several scholars have pointed out that even in contexts of dramatic power differential, such as slavery, cultural borrowings are not passive but, rather, selective and adaptive (Davis 1994; Singleton 1998; Scott 1985).

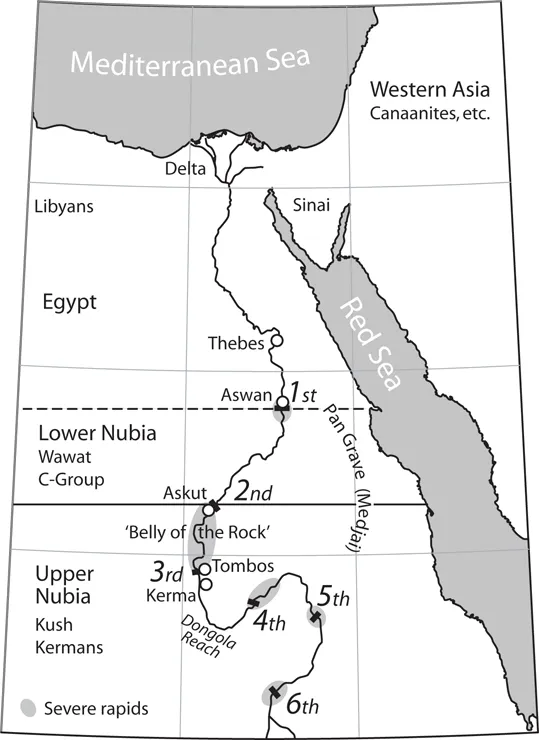

Both sides in such an imperial encounter are interlinked, if nothing else through strategies of dominance and resistance. The complex dynamics inherent in this relationship require the study of both the indigenous society and colonial minority in the context of a specific colonial situation (Gluckman 1949; Balandier 1951: 35, 54–5; Wallerstein 1966; Driessen 1992). The study presented here focuses on the impact of contact and interaction on the colonial communities founded in Nubia (Figure 1.1) by one of the first imperial powers, ancient Egypt. As we will see, cultural influences flowed in both directions as individuals wended their way though the shifting geopolitical situation in the second millennium BC, sometimes affirming and sometimes defying the strong ethnic stereotypes portrayed in Egyptian sources. The first part of this book considers the nature of ethnic identity and examines the ancient Egyptian construction of ethnicity and imperial boundaries derived from the historical record and large-scale archaeological patterning. In the second half of the book, I shift from the regional to the local and the general to the individual through a focus on the archaeological evidence for ethnic identity on Egypt’s southern frontier at Askut (c. 1850–1050 BC) and Tombos (c. 1450–1050 BC). Egyptian colonists, distant from the centers of power, forged new communities, creating their own trajectories of culture contact that came to influence the nature and pace of interaction in Egypt’s far-flung empire.

Figure 1.1 Map of Nubia showing cultural and geographic boundaries.

EGYPT AND NUBIA

One teaches the Nubian to speak Egyptian,

The Syrian and other strangers too.

Say: “I shall do like all the beasts,”

Listen and learn what they do.

The sage Ani, c. 1250 BC

The Syrian and other strangers too.

Say: “I shall do like all the beasts,”

Listen and learn what they do.

The sage Ani, c. 1250 BC

(Lichtheim 1976: 154)

At first glance, Egypt appears to affirm the traditional characterizations of distinct borders and bounded ethnic groups. In a system similar to modern national borders, the Egyptians explicitly established political frontiers that tended to coincide with strategic natural boundaries. Egypt is bounded geographically by the Mediterranean to the north, the mountainous Sinai, Eastern Desert and the Red Sea to the east, the vast expanse of the Libyan or Sahara Desert to the west, and to the south the granite obstacle of the first cataract (Figure 1.1). The Egyptian state was made up of numerous levels of boundaries, all referred to as tash, a term also used in numbers and counting and to indicate limits for measures of all kinds (Hornung 1980). With a people so preoccupied with borders, it should come as no surprise that firm international borders were established delineating the limits of Egyptian conquests and marking the ethnic boundary between Egyptians and other groups, including Nubians. Now part of Egypt and Sudan, Nubia stretches from the first cataract to the Shabaluqa Gorge (sixth cataract), not far from the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile at Khartoum (see map). Lower Nubia is north and Upper Nubia south of the second cataract near the modern Egyptian–Sudanese border. The cataracts consist of outcrops of granite that cut through the bed of the Nile, creating rugged terrain and treacherous rapids that formed an important strategic point of control for Nubians and Egyptians.

Like many modern states and imperial powers, the Egyptians made strong characterizations of ethnic identity that correlated at various levels with their boundaries. Thus, to Middle Kingdom Pharaoh Senwosret III, Nubians are “craven wretches” who will flee from the boundary if challenged. The New Kingdom sage Ani takes an even more extreme view: Nubians and other foreigners are not even really human, and so are compared with animals. Today boundaries and ethnic identities are constructed and reconstructed by us as archaeologists based on patterns of material culture, including the built landscape, but also, in the case of historic civilizations like ancient Egypt, through written records. In the central ideology, the Egyptians existed as a unique and distinctive group, bounded by the Nile delta in the north and the first cataract at Aswan in the south. To step beyond these boundaries was to journey into a wilderness populated by chaotic barbarians. This ideological construction of ethnic identity bears a strong resemblance to modern constructions of ethnic and racial categories, tying skin color to distinctive cultural practices like dress, funerary rites, and so on. This picture of absolute ethnic boundaries is, however, balanced by less formal documents, including administrative records, stories, and personal funerary monuments. These texts often reflect a more fluid situation where ethnic and political boundaries could be crossed with greater ease than the state ideology implied. While Pharaohs and bureaucrats dictated imperial policy from Egypt, Nubian and Egyptian men and women implemented those large-scale plans, forging new communities and creating their own trajectories of culture contact, that came to influence the nature and pace of interaction on Egypt’s far-flung imperial frontiers.

This book investigates the dynamics of Nubia as a frontier, considering both the regional and the local, and, as much as possible given the limitations of the evidence, the collective and the individual. I speak here of a frontier not in Turner’s sense of the modern westward American expansion of individuals bonding together, shedding their cultural baggage and forging a new society (Billington 1967). Both archaeology and texts reveal that Egyptian colonists brought plenty of cultural baggage with them, although I argue below that they nevertheless forged a new society. Neither did the Egyptian frontier operate as a “safety valve” for the disaffected. The Egyptian disaffected fled beyond Egypt’s borders or paid the consequences of rebellion. Indeed, Williams (1999) has argued that Egypt’s hardened Middle Kingdom frontier was meant as much to discourage flight by dissatisfied Egyptians as to prevent Nubian infiltration. Instead, we can see Nubia as a controlled but dynamic zone of contact and interaction between two powerful states and distinctive cultures, ancient Egypt and Kush (Kerma). But, of course, states and cultures do not interact, people do, and so this book will draw on a combination of historical and archaeological evidence to examine some of the contacts between the individuals and communities that made up Egypt’s southern frontier.

If ethnic identities are self-defined and situational, then how can ancient ethnic groups be identified at all? For Egypt, we have the advantage of a rich textual and artistic record that can provide direct access into the minds of ancient people. Historical and art-historical evidence provides a clear view of the construction of ethnic identity in the state ideology. Similar material from more modest sources produced by the literate elite provides a more personalized point of view (see Chapters 2 and 3). But all of these sources are biased towards the Egyptian elite. Archaeological evidence can provide an important corrective as well as yielding insights uniquely its own to the problems under discussion here. The case studies from Askut and Tombos can be placed within a larger archaeological context through the use of older excavation reports and the increasing number of final publications from the Aswan High Dam Salvage Campaign in Lower Nubia. Additionally, a growing archaeological interest in Upper Nubia is gradually bringing this heretofore poorly known region into better focus. The integration of archaeology and text in ancient Nubia provides an opportunity, not only better to understand the nature and dynamics of the construction of political boundaries and ethnic identity in ancient states, but also to assess the role of ethnic stereotypes in state ideology as a legitimating tool for early rulers.

Although some argue that ethnicity is a modern construct, both the origins of the word in classical civilization and ancient examples demonstrate that it existed long before the emergence of modern nation states. Chapter 2 begins with a discussion of the applicability of the concept of ethnicity to the ancient world. The persistent view of ethnicity as essential and thus clearly bounded is then contrasted with more recent theories emphasizing the multi-dimensional nature of boundaries and ethnic identities. Instrumentalists argue that ethnic identities are created to the advantage of individual agents, and thus are mutable and manipulated depending on the individual situation (Royce 1982). Ethnicity is not immutable and essential, but flexible and situational, sometimes existing in very narrow, specific contexts in space and time. The chapter continues with an examination of this dynamic from a different point of view that acknowledges the importance of instrumental contingencies while seeing ethnic identity as grounded in Bourdieu’s notion of the habitus (Bourdieu 1977: 78–93; Jones 1996, 1997).

This chapter also examines the importance of the “other” in defining ethnic identity, with specific reference to ancient Egyptian definitions of the different ethnoi surrounding them. Some have argued that ethnic definitions imposed from the outside are not valid (Royce 1982). Yet ethnic categories can be and often are created by outsiders. In particular, imperial powers create ethnic stereotypes to characterize conquered peoples, usually in order to create or reinforce existing power structures. A fundamental quality that sets ethnicity apart from the habitus or indeed the general concept of culture is the idea of difference (Bourdieu 1977; Barth 1969a; Jones 1996, 1997). Ethnic identities are constructed through cultural difference with relation to the specific cultural practices of ethnic “others” (Díaz-Andreau 1996; Fitzpatrick 1996; Renfrew 1996). Some argue that ethnicity cannot even exist without contact with other groups. The contact itself produces a self-consciousness of difference that leads to the construction of ethnic identity (Comaroff and Comaroff 1992: 235–63).

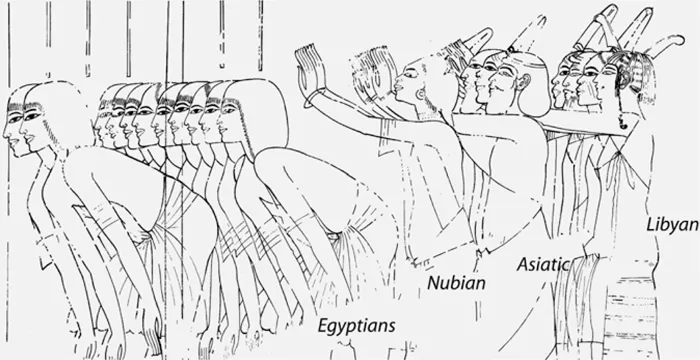

As a result, ethnicity is defined as much by the “other” as itself. External definitions of ethnicity are therefore just as “real” as self-identifications (Hines 1996), and can have real consequences in the context of contact and interaction, particularly when one group tries to dominate another. The political use of the ethnic “other” is particularly applicable to the highly idealized construction of ethnic identities reflected in ancient Egyptian ideology. Egyptian ideology created a topos, or stereotype, of distinctive ethnic categories presenting Egyptians as civilized and foreigners as barbaric enemies (Loprieno 1988). Egyptian art depicts Nubians with stereotypical dark skin, facial features, hairstyles, and dress (Yurco 1996), all very different from Egyptians and the other two ethnic groups, Asiatics and Libyans (Figure 1.2).

The methodology developed in Chapter 3 provides the basis for an examination of identity through patterning in three basic categories of evidence, architecture, material culture, and ritual practice, at the Egyptian frontier community at Askut in Lower Nubia (Chapter 5) and cemetery at Tombos in Upper Nubia (Chapter 6). Assumptions of ethnic groups as distinctive, bounded entities have led archaeologists to conclude that the difficulty of identifying ethnicity archaeologically relates to limitations inherent in the archaeological record (Allaire 1987). But if we recognize that ethnic identities vary situationally, then we would expect patterns of material culture to be complex and overlapping (Hodder 1982a; Wiessner 1983). Both Rogers (1990) and Farnsworth (1992) argue that the archaeological impact of colonial interaction must be assessed through a careful examination of the often subtle ways in which imported objects and practices are integrated into an existing culture. Santley et al. (1987) take a broader view, arguing that ethnicity can be identified through ritual, dress, language, and culinary practices. They separate the archaeological evidence for ethnic identity into larger categories of household and community, distinguishing between domestic and ritual activities within each of these larger contexts. Ritual contexts are particularly important at the community-wide level, appearing archaeo-logically in distinctive architecture and artifact assemblages. Askut contained a community chapel and several household shrines as well as ritual artifacts like censers and fertility figurines. Funerary architecture and practice are a particularly important area where ethnic identity is asserted. Death tears at the fabric of society, and creates opportunities for the reinforcement of existing and negotiation of new roles during rites that lead to the reconfiguration of society for individuals, families, and the larger society after the loss of one of its members (Morris 1987). This can be detected at Tombos through a reconstruction of funerary practices reflected by architecture, grave goods, and burial position.

Figure 1.2 Ethnic stereotypes of Egyptians and foreigners (after Davies 1941: Pl.37).

Stanish (1989) emphasizes the utility of a strong contextual approach focused on the household in determining the ethnic identity of colonists. The domestic assemblage should reflect the material culture of origin, particularly the sub-assemblage that reflects culinary preferences and practices. Through dining etiquette, food preferences, and culinary equipment, meals serve to reaffirm group identity and social structure (Goody 1982). Foodways can be examined at Askut in an analysis of culinary equipment, primarily pottery used for storage, food service, and cooking. ...