eBook - ePub

Spirituality in Social Work Practice

Ronald K. Bullis

This is a test

Share book

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Spirituality in Social Work Practice

Ronald K. Bullis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1996. Currently there is a strong trend in the metal health professions to look at the whole picture when dealing with clients. Religion and spirituality are now officially accepted as a major portion of this picture. In keeping with this trend this book assesses the role of spiritually oriented assessments and interventions in clinical practice. By providing examples of both spiritual cosmologies and anthropologies, it offers a cross-cultural theoretical orientation and therapeutic rationale for spirituality in clinical settings. The book is an essential resource for social workers, mental health counsels, bereavement specialists, professional clergy, and others in the helping professions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Spirituality in Social Work Practice an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Spirituality in Social Work Practice by Ronald K. Bullis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Making Connections Between Spirituality and Social Work Practice

Spirituality and social work practice might seem like strange bedfellows. They have been estranged for so long that it might seem that they have been long divorced with irreconciliable differences. Twenty years ago, it might have seemed that the final divorce decree was issued. Today, the divorce seems neither inevitable, final, nor desirable. Social workers and other mental health professionals are willing, even eager, to discuss spirituality and to apply it to social work assessments and interventions.

This book illustrates how clinicians can integrate spirituality into their work and presents the incredible variety of cross-cultural spirituality. The empirical research discussed in this book (some for the first time) reveals that social workers are using spiritual concepts and techniques in making assessments and interventions. Recent research also demonstrates that social workers are thinking carefully about the ethical implications posed by these spiritual concepts and techniques.

In choosing to employ spiritual concepts and techniques, social workers join other mental health professions and professionals who are doing so. Psychologists, psychiatrists, licensed counselors, and pastoral counselors are all in the process of researching and developing strategies and criteria for use of spiritual assessments and interventions.

RESURGENCE OF SPIRITUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES

There is a resurgence of interest in spirituality, in all its variety, in the United States. A Generation of Seekers (Roof, 1993) empirically examined the religious and spiritual beliefs of the baby boomer generation. The author reported that those more exposed to the counterculture movements of the 1960s are more prone to be unconventional in their religious beliefs and practices. Indeed, they are much more likely to have more spiritual or mystical beliefs than conventionally religious or theistic leanings. Mystics tend to view God as immanent and to value feelings and experiences about God; theists tend to value cognitive and creedal knowledge about God. Roof has indicated that more active mystics and seekers were more likely to view that “God is within us, believe in reincarnation, psychic powers, ghosts, and meditation.” Defining the differences between religion and spirituality is crucial in understanding both the focus of this book and the different ways in which social workers and clients understand spirituality in their practices and in their lives.

DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN RELIGION AND SPIRITUALITY: MORE THAN A DIME’S WORTH OF DIFFERENCE

Social work’s history of defining spirituality mirrors the history of the use of spirituality in social work itself. One of the first social work writers to define religion was Susan Spencer (1956) who defined a religious person as one who holds beliefs about “the affirmative nature of the Universe and man’s duty to do something in addition to advancing his own ends; a belief which furnishes some degree of comfort and strength to the individual” (p. 19). Building upon this notion, Joseph (1988) asserted that religion is “the external expression of faith … comprised of beliefs, ethical codes, and worship practices” (p. 444).

Conversely, spirituality is defined as the “human quest for personal meaning and mutually fulfilling relationships among people, the nonhuman environment, and, for some, God” (Canda, 1988, p. 243). The differences between these two definitions and modes of thought are becoming crystallized within the social work profession. Religion refers to the outward form of belief including rituals, dogmas and creeds, and denominational identity. In this sense, it is perfectly consistent to speak about one’s religion as Methodist and belief in historic statements of belief such as the Apostles’ Creed.

Spirituality refers to the inner feelings and experiences of the immediacy of a higher power. These feelings and experiences are rarely amenable to the political formulations of creedal statements or to theological discriminations. Spirituality, by its very nature, is eclectic and inclusive.

Spirituality is defined here as the relationship of the human person to something or someone who transcends themselves. That transcendent person or value may take a variety of forms—and this definition is intentionally broad. This broad definition is intended to include the enormous variety of transcendent values, concepts, or persons with which people identify as higher sources.

AN ECOLOGY OF CONSCIOUSNESS

The variety of spirituality is illustrated by the variety of the occasion for spiritual experiences. A November 1994 Newsweek poll of 756 adults, with a margin of error of plus or minus 4 percentage points, hints at such diversity (Woodward, 1994). It found that a full 50% feel a deep sense of the sacred all or most of the time during worship services. Interestingly, the research discovered that, even outside church, 45% feel a sense of the sacred during meditation, 68% feel a sense of the sacred at the birth of a child, and 26% feel a sense of the sacred during sex.

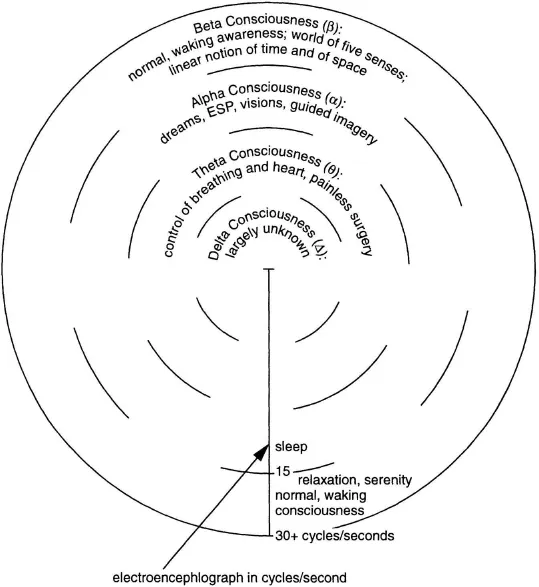

A more operational definition of spirituality is needed. This book asserts that transcendence operationally means a higher altered state of consciousness. A higher state of consciousness means an altered state of consciousness that has a divine or a sacred consciousness. In other words, spirituality is divinely focused altered states of consciousness. Figure 1.1 illustrates the nature of altered states and spirituality and describes how meditation connects with spirituality. As the figure depicts, human beings are capable of several states of consciousness. This figure describes four main states of consciousness. The first and most familiar state is called beta. Beta consciousness is waking consciousness. It is the consciousness that most people experience most of the time. Beta is the state people are in when they drive cars, fill out forms, conduct business, play with their children, and conduct the usual affairs of the day. Indeed, the expression of altered states means any alteration from the usual beta state of consciousness.

The next deeper state is alpha. In most instances, the transition between beta and alpha is slow and gradual. For example, sleep is an alpha consciousness. The transition from wakefulness to sleep is gradual. The stage of consciousness between wakefulness and sleep is called hypnopompic; the stage from sleep to wakefulness is called hypnogogic. These transitional states of consciousness can be very productive for creative thinking and imaginative problem solving.

The alpha state is a deeper level of consciousness. It connotes a less anxious state of consciousness. It is the level of consciousness associated with meditation, prayer, and dreams. In fact, the hypnogogic and hypnopompic stages illustrate the alpha state. The alpha state is the key to the spiritual consciousness. It is here that the beta consciousness characteristics of logic, analysis, and empiricism give way to the alpha consciousness of intuition, poetic thinking, and analogy. The alpha state is a two way street—where the spiritual realities meet the temporal realities, where the earth and the heavens join.

The differences between the beta and alpha states can be described as the differences between reading a newspaper and reading a poem. In reading newspapers, the analytical questions of who, what, when, how, and why are paramount. Newspapers give literal accounts of the facts. That is their job and that is what the public expects of them. In the vintage television series Dragnet, Los Angeles detective Joe Friday always tells witnesses that he wants “just the facts, ma’am, just the facts.” Beta consciousness acknowledges just the literal facts.

Figure 1.1 Ecology of Consciousness (Adapted from Setzer, 1973.)

Reading and understanding poetry, however, requires a different consciousness. It requires the alpha consciousness’ facility with imagery, symbolism, simile and metaphor. In fact, understanding poetry is not the purpose of poetry. The purpose of poetry is to move and to sensitize and to change consciousness—not just to be understood intellectually. In that same way, the parables (poetic teachings) of Jesus and other spiritual leaders are designed to change consciousness, not just to teach a moral principle.

Spirituality requires the same facility as parable and poetry. Spiritual consciousness is invoked and is fed by the power of imagery to overwhelm and to initiate. It is no coincidence that the majority of most religious scripture is in the form or function of poetry. Worship requires alpha consciousness. Worship facilitates consciousness surrender into a deeper, more profound state.

It is no coincidence that sexuality and spirituality occupy common ground. The Song of Songs or the Song of Solomon is an explicitly erotic Biblical book with a long history of spiritual analogy. Neither is it any coincidence that some spirtual terminology, such as referring to being seduced by the spirit or submission (the literal term for Islam) to the will of God, conjures sexual imagery. Sexual imagery connotes the altered consciousness that is indicative of spirituality. Places of worship are, thus, more like bedrooms than classrooms. Places of worship are specifically designed to invoke the alpha, meditative state. Classrooms cater to the beta mind with bright lights, highly technical learning equipment, and students in a hierarchical position vis-a-vis the instructor. Classrooms are designed for linear, analytical, logical thinking. Places of worship, conversely, are designed to initiate alpha thought waves with dim lights, hymns, liturgical poetry, candles, chanting, praying, meditating and other consciousness-altering devices.

The two deepest states, designated delta and theta, can illustrate the most remarkable spirtual consequences. In this stage adepts can undergo painless dentistry, surgery, and childbirth. These stages, thus, manifest perhaps the most dramatic example of how spirtual exercises can influence and control physiological activities. There is, currently, little research on these states. Science is just beginning to scratch the surface of understanding such phenomena. Delta and theta states are rarely even recognized—let alone researched. Suffice to say here that, in every religious tradition there are miracle stories. The future is known, the dead are made live again, the blind are given sight, the lame are made to walk. There are stories where, seemingly, the laws of nature are contradicted. As a matter of fact, they are called miracles only because they offend the laws of the beta consciousness. Telepathy, clairvoyance, and spiritual healings all contradict logical and rational thinking. In alpha consciousness, as in dreams and trances, such miracles are commonplace.

SPIRITUALITY IN SOCIAL WORK HISTORY

Charlotte Towle in Common Human Needs, first published in 1945 and revised at least twice (1952 and 1957), recognized early on the significance of spirituality in social work practice. Borrowing a line from the Gospels, in a section titled “Spiritual forces are important in man’s development,” she asserts that “man does not live by bread alone” (Matthew 4:4, Revised Standard Version)1. She relates that spiritual needs “must be seen as distinct needs and they must also be seen in relation to other human needs” (p. 8). She also wrote that “through the influence of religion the purpose of human life is better understood and a sense of ethical values understood” (p. 8).

Traditionally, social work literature has reluctantly addressed religion’s or spirituality’s impact on clinical practice. Loewenberg (1988) has synthesized the reasons for this neglect that include the historic rift between the religious and psychoanalytic movements; the alleged atheistic orientation of social workers (Spencer, 1956); and the economic, political, and professional competition between religious professionals and secular social workers (Marty, 1980). For the most part spirituality in social work literature is conspicuous only by its absence. Loewenberg (1988) writes that “social work literature generally has ignored or dismissed the impact of religion on [social work] practice” (p. 5). In fact, he despairs over the small amount of space Towle gives to spirituality in her book. It is gratifying that she gave such a clear and cogent description of the significance of spirituality and religion. The glass can be half full, too.

Spiritual traditions incorporate potent terms that are useful for social work practice. The Hebrew words tzedakah and hesed mean, respectively, short-term giving (usually money) and a longer term relationship characterized by “loving-kindness” (Linzer, 1979). Islamic social concepts include maslalah (public interest) including the notions of collective good over private interest and the responsibility of the Ummah (Islamic community) for the common well-being of all its members (Ali, 1990). The term karuna (compassion) or the Sanskrit term metta (loving-kindness) are terms from Buddhist thought (Canda & Phaobtong, 1992). In fact, Dorothea Dix’s funeral service included the Gospel passage:

I was hungry and you gave me food: I was thirsty and you gave me drink; I was a stranger and you took me in. 1 was naked and you clothed me: I was sick and you visited me: I was in prison and you visited me. (Matt. 25:35-36)

Another misconception is that spirituality has more heavenly concerns whereas social work has more earthly concerns. To suggest that spirituality and religion are exclusively preoccupied with otherworldly concerns is a gross exaggeration—an exaggeration with a short memory about the history of social work.

The pioneers of the social work profession and its values were intimately connected with religious and spiritual traditions (Stroup, 1986). Jane Addams founded Hull House, led the settlement house movement, and is generally regarded as a seminal figure in professional social work. After graduating from Rockford Seminary (later Rockford College), she traveled to Europe and discussed social problems of the day with current leaders. After Europe, she returned home and soon became depressed. She found the social life “a waste of time” and university men “dull” (Stroup, 1986, p. 8). Then, she found both a challenge and an outlet for her humanitarian concerns. At age 25 she joined the Presbyterian Church, and while at Hull House she joined the Congregational Church (now the United Church of Christ). These faiths offered her religious inspiration and a focus for her service with the poor.

Another form of evidence refutes the otherworldly assertion. In 1978, for example, 46% of all charitable dollars and an equivalent amount of volunteer giving-in-kind were from religious organizations (Marty, 1980). Even this contribution does not adequately consider the long history of Jewish Social Services, Catholic Charities, Lutheran Social Services and any number of other religiously or spiritual motivated organizations. This also does not account for the big and small charities and programs supported by local religious or spiritual groups.

RATIONALES FOR THE USE OF CLINICAL SPIRITUALITY

This section discusses a series of reasons for using spirituality in clinical practice. These rationales flow from the preceeding section and from the data reported in the following chapter.

1. Social work, historically and philosophically, is connected to spirituality. It was noted earlier that early social work leaders were influenced by spirituality. Chapter 2 presents empirical data that indicate that spirituality is a very prevalent factor in current social work practice. Philosophically, both social work and spirituality promote common interests and self-respect.

Social work and spirituality are natural allies in personal and social healing. Social work and spiritual professionals have similar goals. Both wish to promote the healing of personal and community strife, violence, and ignorance.

Although the goals are similar, the means are not—nor should they be. Professionals concerned with spirituality are generally concerned with the development of the inner person. Mystics are suspicious of social progress at the expense...