![]()

1 A perspective on judgment and choice: Mapping bounded rationality

Daniel Kahneman

Nobel Laureate presentation, 28th International Congress of Psychology, Beijing, China, 8–13 August 2004

The work cited by the Nobel committee was done jointly with the late Amos Tversky (1937–1996) during a long and unusually close collaboration. Together, we explored a territory that Herbert A. Simon had defined and named – the psychology of bounded rationality (Simon, 1955, 1979). This article presents a current perspective on the three major topics of our joint work: heuristics of judgment, risky choice, and framing effects. In all three domains, we studied intuitions – thoughts and preferences that come to mind quickly and without much reflection. I review the older research and some recent developments in light of two ideas that have become central to social-cognitive psychology in the intervening decades: the notion that thoughts differ in accessibility – some come to mind much more easily than others – and the distinction between intuitive and deliberate thought processes.

The first section, Intuition and accessibility, distinguishes two generic modes of cognitive function: an intuitive mode in which judgments and decisions are made automatically and rapidly and a controlled mode, which is deliberate and slower. The section goes on to describe the factors that determine the relative accessibility of different judgments and responses. The second section, Framing effects, explains framing effects in terms of differential salience and accessibility. The third section, Changes or states: Prospect theory, relates prospect theory to the general proposition that changes and differences are more accessible than absolute values. The fourth section, Attribute substitution: A model of judgment by heuristic, presents an attribute substitution model of heuristic judgment. The fifth section, Prototype heuristics, describes that particular family of heuristics. A concluding section follows.

Intuition and accessibility

From its earliest days, the research that Tversky and I conducted was guided by the idea that intuitive judgments occupy a position – perhaps corresponding to evolutionary history – between the automatic operations of perception and the deliberate operations of reasoning. Our first joint article examined systematic errors in the casual statistical judgments of statistically sophisticated researchers (Tversky & Kahneman, 1971). Remarkably, the intuitive judgments of these experts did not conform to statistical principles with which they were thoroughly familiar. In particular, their intuitive statistical inferences and their estimates of statistical power showed a striking lack of sensitivity to the effects of sample size. We were impressed by the persistence of discrepancies between statistical intuition and statistical knowledge, which we observed both in ourselves and in our colleagues. We were also impressed by the fact that significant research decisions, such as the choice of sample size for an experiment, are routinely guided by the flawed intuitions of people who know better. In the terminology that became accepted much later, we held a two-system view, which distinguished intuition from reasoning. Our research focused on errors of intuition, which we studied both for their intrinsic interest and for their value as diagnostic indicators of cognitive mechanisms.

The two-system view

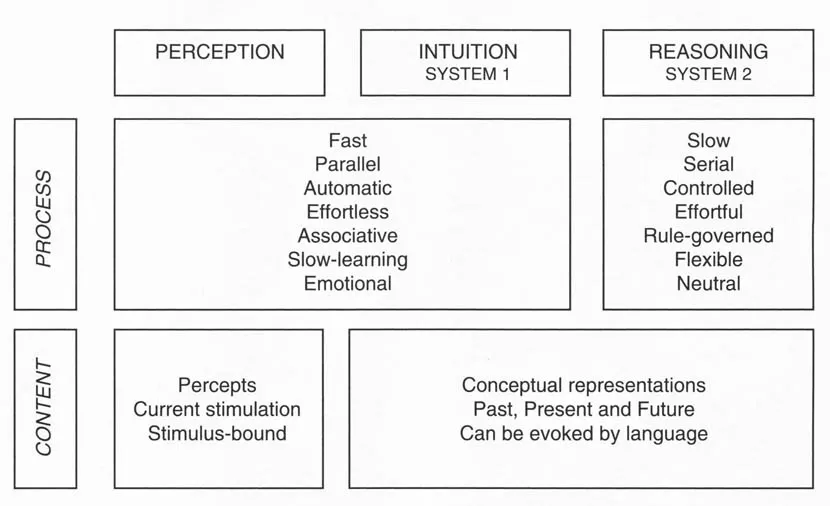

The distinction between intuition and reasoning has been a topic of considerable interest in the intervening decades (among many others, see Epstein, 1994; Hammond, 2000; Jacoby, 1991, 1996; and numerous models collected by Chaiken & Trope, 1999; for comprehensive reviews of intuition, see Hogarth, 2001; Myers, 2002). In particular, the differences between the two modes of thought have been invoked in attempts to organize seemingly contradictory results in studies of judgment under uncertainty (Kahneman & Frederick, 2002; Sloman, 1996, 2002; Stanovich, 1999; Stanovich & West, 2002). There is considerable agreement on the characteristics that distinguish the two types of cognitive processes, which Stanovich and West (2000) labeled System 1 and System 2. The scheme shown in Figure 1.1 summarizes these characteristics: The operations of System 1 are typically fast, automatic, effortless, associative, implicit (not available to introspection), and often emotionally charged; they are also governed by habit and are therefore difficult to control or modify. The operations of System 2 are slower, serial, effortful, more likely to be consciously monitored and deliberately controlled; they are also relatively flexible and potentially rule governed. The effect of concurrent cognitive tasks provides the most useful indication of whether a given mental process belongs to System 1 or System 2. Because the overall capacity for mental effort is limited, effortful processes tend to disrupt each other, whereas effortless processes neither cause nor suffer much interference when combined with other tasks (Kahneman, 1973; Pashler, 1998).

Figure 1.1 Process and content in two cognitive systems.

As indicated in Figure 1.1, the operating characteristics of System 1 are similar to the features of perceptual processes. On the other hand, as Figure 1.1 also shows, the operations of System 1, like those of System 2, are not restricted to the processing of current stimulation. Intuitive judgments deal with concepts as well as with percepts and can be evoked by language. In the model that is presented here, the perceptual system and the intuitive operations of System 1 generate impressions of the attributes of objects of perception and thought. These impressions are neither voluntary nor verbally explicit. In contrast, judgments are always intentional and explicit even when they are not overtly expressed. Thus, System 2 is involved in all judgments, whether they originate in impressions or in deliberate reasoning. The label intuitive is applied to judgments that directly reflect impressions – they are not modified by System 2.

As in several other dual-process models, one of the functions of System 2 is to monitor the quality of both mental operations and overt behavior (Gilbert, 2002; Stanovich & West, 2002). As expected for an effortful operation, the self-monitoring function is susceptible to dual-task interference. People who are occupied by a demanding mental activity (e.g., attempting to hold in mind several digits) are more likely to respond to another task by blurting out whatever comes to mind (Gilbert, 1989). The anthropomorphic phrase “System 2 monitors the activities of System 1” is used here as shorthand for a hypothesis about what would happen if the operations of System 2 were disrupted.

Kahneman and Frederick (2002) suggested that the monitoring is normally quite lax and allows many intuitive judgments to be expressed, including some that are erroneous. Shane Frederick (personal communication, April 29, 2003) has used simple puzzles to study cognitive self-monitoring, as in the following example: “A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?” Almost everyone reports an initial tendency to answer “10 cents” because the sum $1.10 separates naturally into $1 and 10 cents and because 10 cents is about the right magnitude. Frederick found that many intelligent people yield to this immediate impulse: Fifty percent (47/93) of Princeton students and 56% (164/293) of students at the University of Michigan gave the wrong answer. Clearly, these respondents offered a response without checking it. The surprisingly high rate of errors in this easy problem illustrates how lightly the output of System 1 is monitored by System 2: People are not accustomed to thinking hard and are often content to trust a plausible judgment that quickly comes to mind. Remarkably, errors in this puzzle and in others of the same type were significant predictors of intolerance of delay and also of cheating behavior.

In the examples discussed so far, intuition was associated with poor performance, but intuitive thinking can also be powerful and accurate. High skill is acquired by prolonged practice, and the performance of skills is rapid and effortless. The proverbial master chess player who walks past a game and declares, “White mates in three,” without slowing is performing intuitively (Simon & Chase, 1973), as is the experienced nurse who detects subtle signs of impending heart failure (Gawande, 2002; Klein, 1998). Klein (2003, chapter 4) has argued that skilled decision makers often do better when they trust their intuitions than when they engage in detailed analysis. In the same vein, Wilson and Schooler (1991) described an experiment in which participants who chose a poster for their own use were happier with it if their choice had been made intuitively than if it had been made analytically.

The accessibility dimension

A core property of many intuitive thoughts is that under appropriate circumstances, they come to mind spontaneously and effortlessly, like percepts. To understand intuition, then, one must understand why some thoughts come to mind more easily than others, why some ideas arise effortlessly and others demand work. The central concept of the present analysis of intuitive judgments and preferences is accessibility – the ease (or effort) with which particular mental contents come to mind. The accessibility of a thought is determined jointly by the characteristics of the cognitive mechanisms that produce it and by the characteristics of the stimuli and events that evoke it.

The question of why particular ideas come to mind at particular times has a long history in psychology. Indeed, this was the central question that the British empiricists sought to answer with laws of association. The behaviorists similarly viewed the explanation of “habit strength” or “response strength” as the main task of psychological theory, to be solved by a formulation integrating multiple determinants in the history and in the current circumstances of the organism. During the half century of the cognitive revolution, the measurement of reaction time became widely used as a general-purpose measure of response strength, and major advances were made in the study of why thoughts become accessible – notably, the distinctions between automatic and controlled processes and between implicit and explicit measures of memory. But no general concept was adopted, and research on the problem remained fragmented in multiple paradigms, variously focused on automaticity, Stroop interference, involuntary and voluntary attention, and priming.

Because the study of intuition requires a common concept, I adopt the term accessibility, which was proposed in the context of memory research (Tulving & Pearlstone, 1966) and of social cognition (Higgins, 1996) and is applied here more broadly than it was by these authors. In the present usage, the different aspects and elements of a situation, the different objects in a scene, and the different attributes of an object – all can be more or less accessible. Moreover, the determinants of accessibility subsume the notions of stimulus salience, selective attention, specific training, associative activation, and priming.

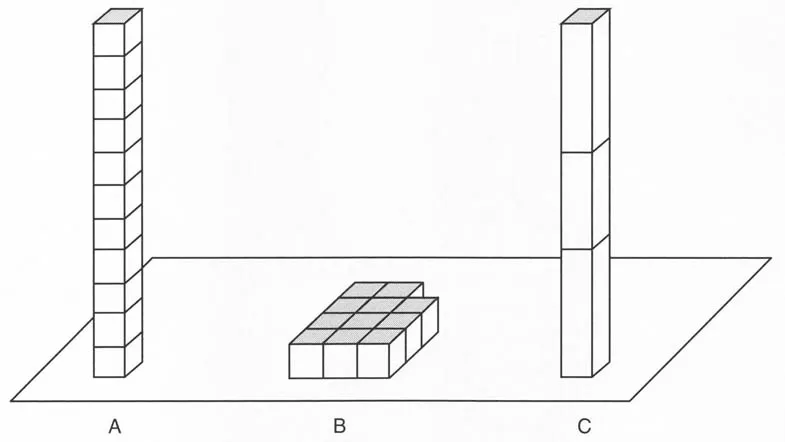

For an illustration of differential accessibility, consider Figures 1.2A and 1.2B. As one looks at the object in Figure 1.2A, one has immediate impressions of the height of the tower, the area of the top, and perhaps the volume of the tower. Translating these impressions into units of height or volume requires a deliberate operation, but the impressions themselves are highly accessible. For other attributes, no perceptual impression exists. For example, the total area that the blocks would cover if the tower were dismantled is not perceptually accessible, though it can be estimated by a deliberate procedure, such as multiplying the area of the side of a block by the number of blocks. Of course, the situation is reversed with Figure 1.2B. Now, the blocks are laid out, and an impression of total area is immediately accessible, but the height of the tower that could be constructed with these blocks is not.

Figure 1.2 The selective accessibility of natural assessments.

Some relational properties are accessible. Thus, it is obvious at a glance that Figures 1.2A and 1.2C are different but also that they are more similar to each other than either is to Figure 1.2B. Some statistical properties of ensembles are accessible, whereas others are not. For an example, consider the question “What is the average length of the lines in Figure 1.3?” This question is easily answered. When a set of objects of the same general kind is presented to an observer – whether simultaneously or successively – a representation of the set...