- 346 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Why do contraceptive practices work for some couples and not for others? How do couples decide the number of children they want? What are the implications of family design in terms of the "population explosion?"Family Design is a thoroughly documented study undertaken by Social Research, Inc., for the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Based on intensive interviews with 409 husbands and wives, it applies the framework of family sociology to a problem that has previously been studied mainly from the demographic point of view.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Family Design by Lee Rainwater in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Marriage & Family Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

THE QUESTION of the number of children they will have is a vital, complex, deeply involving one for American couples. Though some couples maintain an attitude of fatalism and vague hopefulness about the size their families may eventually reach, most give a good deal of active consideration to the number of children they really want and can afford (psychologically, socially, economically) and to ways of achieving this goal. In doing so couples deal with many kinds of conflicts — conflicts between their own views and those they feel society offers as appropriate, conflicts between themselves, mixed feelings within themselves. These conflicts can apply to both the question of the family size preferred and to the means for seeing that preference becomes a reality. Some couples experience all of this in a context of not being able to have all of the children they want, but most are concerned with the problem of not having more children than they want.

With respect to family size preferences, a couple’s problem is essentially that of coming to some successful resolution of (1) each individual’s desires with those of his partner, and (2) their joint desires with their perception of the society’s norms about family size. The technology for accomplishing these goals, contraception, does not make the task easy—no method now on the market is regarded as really perfect, each makes demands on the user, each has certain difficulties people would like to avoid, and all have the disadvantage of reminding one of the unfortunate necessity to limit and coerce nature, and of the necessity for being rational about such private and disturbing aspects of the human state as sexual relations and the genitals. Almost all of the methods are known to be imperfect in their effectiveness, which introduces a very disturbing note of uncertainly into what is already an emotionally complex situation. In sum, the individual husband or wife is confronted with

- a demanding social task of integrating personal, marital, and cultural demands about an appropriate number of children

- by means which require conscious attention to usually avoided sexual aspects of marital living

- and by means which, furthermore, are believed to have an alarming potential to fall short of 100 per cent effectiveness.

All of this becomes important when considering problems of encouraging effective family planning because each of the difficulties and challenges enumerated above can repercuss on the use and choice of contraceptive methods. Attitudes having to do with feelings about how many children one should have can affect contraceptive behavior, as when a couple resolves differences between them in desired family size by having “accidents” which are then blamed on the method, or chooses a highly reliable method only after having enough children to feel above social criticism and thus keep peace in the family. Similarly, couples who choose a method they regard as not 100 per cent effective may end up practicing the method rather carelessly on the ground that “it’s not much good anyway” (this often happens with rhythm). And attitudes and feelings about sexual relations and the genitals can condition both the choice of contraceptive method and the care in practicing it.

Most of these themes can be seen in the following discussion by a woman in her early thirties who has four children.

I have a daughter who was born in 1949, and a son born in 1951, and then in 1953 we had another daughter and finally we had our youngest, a boy, in 1955. [Do you want more?] Heavens, no! I’m 34 and my husband is getting close to 40. I like to be young with my children and enjoy them, and since we got married so darned young I want time alone later. My husband’s in complete agreement with me. With the high cost of education and the necessity of having a child go to college we would be foolish to have more. I used a diaphragm before and after our children were born until I started using the pill (about three years ago). I hated the diaphragm and so did my husband—it was messy and miserable. I’m so glad we have the pill. We both have complete faith in it. It is such a convenient thing to pop a pill in your mouth every morning. I’m completely sold on it.

An interest in children and a concern with parenthood seem universais of the human condition. Most men and women in all cultures are concerned with themselves as parents and with how their children fare. Parenthood is thus a deeply significant biological, psychological, and social fact of life. As such, the dynamics of parenthood and child training have been central concerns of all of the behavioral sciences from their inceptions; a great deal of the total research effort of psychology, sociology, and anthropology in recent decades has been concerned in one way or another with having and rearing children, whether the particular concern be child rearing practices, socialization to adult roles, intellectual or personality or moral development, mental health problems, processes of identification, or any of a number of other possible specifications of the general question of parent-child relations and the development of children into adult members of their society.

It is all the more curious then, that, aside from demographers, social scientists have shown only a casual interest in how couples come to have the particular number of children they have, and in the consequences of having a particular number of children. While the ethnographer may note in passing the value a group places on having many children, or the child-training specialist may comment upon the importance of older siblings in socializing the child, there has been little concentrated attention devoted to number as an important variable in how parents and children live their lives. (There has been somewhat more concern among psychologists with order of birth as this affects life experiences.)

In the last few years social realities at home and abroad have focused increasing attention on this question of number of children. As the death rate has declined in underdeveloped parts of the world, the absence of a similar decline in birth rates has meant that family size and population have grown rapidly, effectively slowing the rate of economic growth at the same time that appetites for a higher standard of living and greater national strength have burgeoned. Concern over these facts has led to a recent increase in research efforts to understand the dynamics of family size, and to practical programs intended to encourage couples in underdeveloped lands to limit their families. It seems clear that both research and practical programs will be greatly increased in the next few years as fear of the “population explosion” mounts.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the dramatic postwar “baby boom” focused interest on the factors behind the apparent change toward large families. More recently, an increasing awareness of the problem of “residual” and apparently ineradicable poverty, coupled with the knowledge that poor couples are those most likely to have more children than they can support or want, has directed interest to this group’s family size norms and family planning behavior. While there is now in this country little sense of great urgency about domestic population problems, there is nevertheless a growing awareness that a prosperous economy is not immune to the problems of having to support too many people.

It is a mistake, however, to regard research on these subjects as simply an exercise in the application of social science to a practical problem. Much can be learned about families that is of basic social psychological interest from an examination of the ways husbands and wives cope with the biological facts of procreation, the processes of goal formation and decision making concerning family size, the motives that operate to condition family size goals and the choice of methods to achieve these goals. The choices couples make in their efforts to control conception have a fatefulness for their lives together that few other choices in marriage have. The ways they make these choices, just as much as the choices themselves, focus a strong light on the inner working of the family as a social system, and on the individual personalities of its heads. Studies of family planning and limitation offer promise as a testing ground for theories about family functioning, and as a fertile field for discovering insights into the forces and processes which operate as men and women design and build families.

This study has two main focuses: First, what are the factors that lie behind the goals of family size that people set for themselves and what are the social norms they apply in evaluating their own and other people’s family sizes; second, what factors affect the effectiveness with which couples apply family limitation methods, if any, to achieve their own family size goals. With respect to the latter, this study tests some of the hypotheses advenced in an earlier study (Rainwater, 1960). With respect to the first goal, we have sought to develop an understanding of family size norms and goals without clearly formulated prior hypotheses.

As will be apparent in the discussion of method and sample that follows, this study must be regarded as exploratory, though based on a somewhat larger sample than the earlier study mentioned above, and following a more structured approach to the analysis of data. Some of the findings reported here are similar to those developed by other researchers; others have not been observed before, or have been observed only to be discarded as unsupported by adequate data. In any case, although we have avoided a reiteration of tentativeness in what follows, the findings reported here should be understood as suggestive and subject to revision after more intensive study and more extensive sampling. The questions are complex enough, however, for this to be inevitable for any single study; more secure knowledge about family size and family limitation can come only from a multiplicity of research efforts.

The study sample

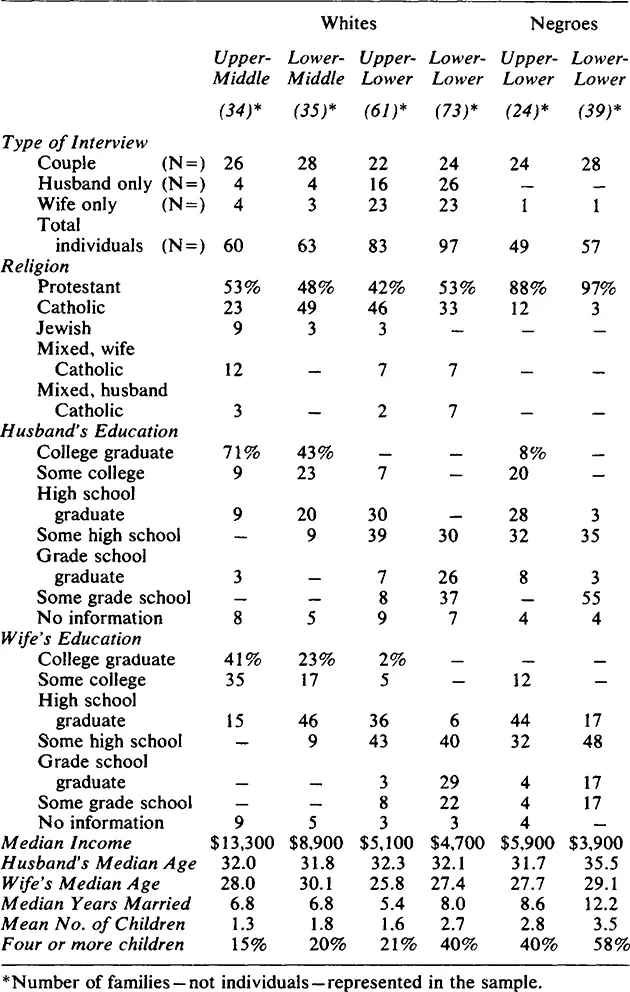

The research is based on interviews with 409 individuals –95 of these interviews were also used in an earlier study (Rainwater, 1960). One hundred and fifty-two couples, and 50 men and 55 women not married to each other were interviewed. Thus, 257 families are represented. The interviews averaged 2i hours in length for each respondent. Of the couples interviewed, in 53 per cent of the cases the husband and wife were interviewed at the same time. This allowed some check on the extent to which interviews with husbands and wives at different times created a bias in the later interview because of prior discussions between the spouses. We found no evidence in our analysis that the responses of those couples not interviewed simultaneously differed in any systematic way from those of couples interviewed at the same time. (This does not mean, however, that a study which seeks more precise quantitative measures of the variables under study could safely ignore the desirability of simultaneous interviews.) Of the total number of families included in the sample (257), the majority (185) lived in Chicago, forth-five lived in Cincinnati, and 32 in Oklahoma City.

The interviews were selected by a purposive sampling method organized around quotas for class and religion groupings. We sought approximately equal numbers of interviews from whites of the upper-middle, lower-middle, upper-lower, and lower-lower classes, and from Negroes of the upper-lower and lower-lower classes (budget limitations prevented our interviewing middle class Negroes). Within each of the white class groups, we established quotas for Catholics and non-Catholics. In order to assure some correspondence in family stage of the couples in each of these groups, quotas were set for each in terms of the age and duration of marriage.

Class, race, and religion, then, represent the three main variables in which we are interested. By limiting the sample to couples in which the wife was under forty years of age and by achieving a fairly matched balance in terms of stages of the family cycle within each of these groups, we sought to highlight whatever influence these factors, and the characteristics of the marital relationship related to them, have on family size preferences and family planning behavior.

Table 1-1 indicates some of the social and familial characteristics of our sample in each of the four social class groups for whites and two social class groups for Negroes. From the table it is apparent that these class-race groups are fairly comparable in terms of number of years of marriage except in the case of lower-lower class Negroes. The biasing effect of this latter group’s having been married longer is offset somewhat, however, by the fact that separations are more common in the group; the difference in median number of years of cohabitation with a husband would be less than the difference shown in the table.

The four social classes that concern us in this study may be briefly characterized as follows:

The upper-middle class is composed of the families of professionals, executives, and business proprietors who are established in their occupations, who exercise important authority in their professional and business organizations, and who generally earn well above average incomes from these activities. The incomes of some of the professionals average quite a bit below those of the business executives and proprietors, but they are accorded similar prestige because of the value placed on their advanced training, autonomy, and learned activities. Upper-middle class families live in residential areas that are well above average in reputation and regard themselves as the better educated and more sophisticated group in their communities. They take it for granted that their children (both sons and daughters) will complete college, and that the sons will probably continue into graduate or professional schools. They tend to be quite active in voluntary associations, and to provide the leadership for these groups. A majority of the upper-middle class men in our sample are under 33 years of age, so it should be noted that they are just beginning their careers, are on the way toward mature responsibility at upper-middle class occupational levels, and see before them at least twenty years of career advancement and hard work to achieve it. (This is in strong contrast to most of the lower class respondents who, at the same age level, see their own work futures as not dramatically different from their present activities and responsibilities.) About 12 per cent of the population in a city like Chicago can be classified as belonging to this class.

Table 1-1:

Characteristics of the Study Sample

Characteristics of the Study Sample

The lower-middle class is composed of the families of white-collar workers who do not exercise important managerial or autonomous professional authority, and of the families of skilled workers and foremen who, though engaged in “blue-collar” work, live in a way that conforms to the model set by the white-collar portion of the group. Most of these men and women graduated from high school, and quite a few of the men completed college. Their education, however was not directed to the higher managerial or professional activities of the upper-middle class. They are engaged, instead, in more routinized occupations, as accountants, engineers, supervisors of clerical workers, etc. Lower-middle class families live in good, average neighborhoods in houses or apartments which they strive to maintain in attractive and respectable ways, but they do not place emphasis on sophistication and organized good taste. Their organizational activity is not as extensive as that of the upper-middle class and they participate more as followers than as leaders (except in organizations that do not include upper-middle class members). About 29 per cent of Chicago’s population falls in this group.

The upper and lower portions of the working class include the majority of the population in most urban areas.

The upper-lower class includes the larger portion of the group (46 per cent) of Chicago’s total population) and is characterized by greater prosperity and stability than the lower-lower class. Upper-lower class workers generally are in semi-skilled and medium-skilled work; they are in manual occupations or in responsible but not highly regarded service jobs such as policemen, firemen, or bus drivers. They have generally had at least some high school education. Their families live in reasonably comfortable housing, in neighborhoods composed mainly of other manual and lower-level service workers. Although people in this group tend today to regard themselves as living the good life of average Americans, they are still aware that they do not have as much social status or prestige as the middle class white-collar worker or the highly-skilled technician and factory foreman.

The lower-lower class represents approximately one-quarter of the working class and about 13 per cent of the population of a city like Chicago. The people in this group are very much aware that they do not participate fully in the good life of the average American; they feel at the “bottom of the heap” and consider themselves at a disadvantage in seeking the goods that the society has to offer. They generally work at unskilled jobs, and often they work only intermittently or are chronically unemployed. Few people in this group have graduated from high school, and a great many have gone no further than grammar school. They live in slum and near-slum neighborhoods, and their housing tends to be cramped and deteriorated. Although many earn fairly good wages when they work ($75 to $100 per week is not uncommon), the seasonal or intermittent nature of their jobs and their relatively impulsive spending habits often prevent them from maintaining what most Americans regard as a “decent” standard of living.

Method of analysis

As Davis and Blake (1956) have noted, fertility in modern Western society has come to be very much a function of contraceptive practice, and the factors that operate in other societies to lower fertility are no longer relevant. Thus, although in the nineteenth century, postponement of marriage was important in keeping family size within tolerable limits (Banks, 1954), even this custom seems to have become superfluous in our time. Of all of the possible voluntary influences on fertility, only contraception seems really important in our own society, and variations in fertility from time to time or group to group can be understood as in large part due to the practice or non-practice of contraceptive methods. This practice, in turn, is a function both of a desire for children and of an ability to practice contraception effectively. We are concerned in this study with both these aspects of family limitation, voluntary abstention from contraception because pregnancy is desired, and abstention from or ineffective practice of contraception that arises from factors other than desired family size. Of the many di...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Family Design

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Social class and conjugal role-relationships

- 3 Sexual and marital relations

- 4 Family size preferences

- 5 Rationales for family size

- 6 Motivations for large and small families

- 7 Family limitation and contraceptive methods

- 8 Effective and ineffective contraceptive practices

- 9 Medical assistance for family limitation

- 10 Conclusions

- APPENDIX A Role Concepts and Role Difficulties

- APPENDIX B Interview Guide

- REFERENCES CITED

- INDEX