![]()

Chapter 1

Unchanging Architecture and the Case for Alteration

Nietzsche said, ‘The purpose of our Palaces and public gardens is to maintain the idea of order.’

(quoted by John Pawson)

ALL BUILDINGS, ONCE HANDED OVER by the builders to the client, have three possible fates, namely to remain unchanged, to be altered or to be demolished. The price for remaining unchanged is eventual loss of occupation, the threat of alteration is the entropic skid, the promise of demolition is of a new building. For the architect, the last course would seem the most fruitful.

In a perfectly functioning state, according to the precepts of functionalism, buildings would either fulfil their purpose or be demolished, except perhaps for a few exceptions. Alteration would be unknown. Through forethought and prescience, buildings would remain unchanged from the moment of their inception to their eventual demise. In such a world, devoid as it would be of any taint of sentiment, what might be the qualities that would save a building from destruction?

The functionalists were the early saints of Modernism, even though sometimes their beliefs seem to float between the moral and the aesthetic, deserting one for the other in the face of argument. Their intention was to keep the purposes of Modernism free from doubt. John Summerson has said that the one singular characteristic of Modernist theory was the commitment to a social programme, that is architecture in the service of progressive tendencies in society. He further stated that without this, architectural theory would be indistinguishable from architectural thought since the eighteenth century, although this was said before the onset of postmodern writings. In some less than obvious way, functionalism is the agent of this commitment: function is generally supposed to envelop without contradiction progressive social purposes. The Machine Aesthetic presumes a clarity of purpose, as that which the machine itself has. The Machine is the vehicle that will carry society towards Utopia.

In contrast to the machine, the difficulties in defining the elusive exact correspondence between function and built form is that which hinders the realization of such a perfect state, but does not entirely disprove its propositions. It may be that the elusiveness is a result of compounding the animate with the inanimate.

Le Corbusier’s own attitude would seem to have been made explicit by his claiming that the house is to be ‘a machine to live in’. But as Philippe Boudon has pointed out, this is not without ambiguity. He quotes from Le Corbusier’s notes:

The dictionary tells us that machine is a word of Latin and Greek origin meaning art or artifice: ‘a contrivance for producing specific effects’ … which forms the necessary and sufficient framework for a life that we are able to illumine by raising it above the level of the ground through the medium of artistic designs, an undertaking dedicated in its entirety to the happiness of man.1

Thus we read the clear qualities of necessity and sufficiency amalgamated with ‘the medium of artistic designs’, with no contradiction recognized by the author therein.

In several instances in later architectural theory, function is equated with Vitruvian commodity. Robert Venturi, for instance, at the Art Net conference in London in the 1970s2 said that Classic architecture consisted of Commodity, Firmness and Delight, as propounded by Vitruvius, and that Modern architecture consisted of Firmness plus Commodity equals Delight. In making this proposal, it is evident that he was relying on the commonly held assumption that the commodity of Vitruvius is the equivalent of function in Modernist theory. Dr Robin Evans once observed that in referring to commodity, Vitruvius gives the example of the rich merchant leaving his house and of how the design of the portal can help to give an appropriate setting as he emerges into the city. Thus in this exposition there are traces of the client’s vanity and status that are at odds with the concept of efficient, economic and selfless function in the service of social progress.

Function assumes qualities of precision and absence of ambiguity. Perhaps it is because these qualities are manifest in the architectonics of Modernist built form that they are used through allusion to make reference to the assumed conduct of life within the buildings. To put it more succinctly, following Le Corbusier’s pronouncement that the house is a machine for living in, it would seem that the precision of servicing, construction and structure of Modernist buildings has been commonly taken as a metaphor for the life intended to be led in such buildings. The actual conduct of life, of course, is always more elusive than the architect’s will.

One can suggest that this metaphoric link was the means by which Modernist tendencies identified with the forces for social progress, that there was an assumed parallel between architectonic reform and the contemporaneous attempt to reform the populace’s thought and behaviour, to bring into being an intelligent and cohesive proletariat. By this assumption Modernist buildings could be thought of as active agents in the crusade for social progress, and thus a means of connected commitment between theory and practice.

In addition a further attraction might be that it offered a way by which the architect might allay the loneliness of genius through such a social commitment. Such an alliance might be said to underlie the various progressive crusades in architecture in the twentieth century.

Latter-day proponents of functionalism such as Cedric Price and Peter Blundell Jones have sought to re-establish its potency with arguments for a greater clarity with regard to the workings and purposes of buildings. However, this has a key difficulty: precision is a difficult quality to apply to thought and behaviour, which are crucial components of inhabitation. Intent in particular has no immediate spatial requirement.

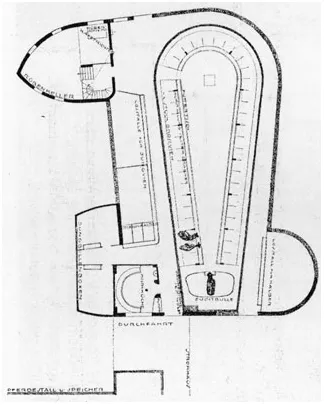

Peter Blundell Jones talks very persuasively of the attributes of functionalism, using as primary evidence the cowshed and other farm buildings at Garkau near Lubeck by Hugo Haring3 (Figure 1.1). It is a further difficulty of functionalism indicated by this choice of paradigm, that proving the case for one building by definition disqualifies it for exact translation to others, because of the dependence on the particulars of specification. Philippe Boudon, of whom the reader will hear more later, expressed a similar observation thus: ‘The desire for authenticity and truth of the function …, the rejection of connotation (since the form must come strictly from the function) leads to incommunicability … All this puts modern architecture in a very precarious position: incapable of being taught because of its incommunicability’.4

1.1 Plan of the farm at Lubeck by Hugo Haring, 1922–26

Cedric Price long argued for the demolition of obsolete buildings, buildings that have outlived their usefulness; at the time of his untimely death, he had been trying to prevent Camden Council proposing one of his own buildings for listing to save it from demolition. A lesser but more ennobled mind has recently called for the demolition of a certain building on the grounds that it was a ‘waste of space’, and coincidentally in the way of one of his own proposals. Of course the intellectual integrity of the first puts the second to shame, and perhaps all doctrines have a raw edge, but the idea of obsolescence in architecture is quite a strange one. It is peculiarly distinct and separate from the intrinsic qualities, whether spatial or physical, of the building that is in question, the qualities for which a building is liable to be considered for preservation.

It is difficult not to associate it with censorship, or at least with a licence to censor. Thus in a functionalist model, all works of architecture stand in danger of being considered at some time or other, by some agency or other, as a waste of space. Because of the uncertainties in being able to fit function tightly to the built form, the idea of obsolescence is amenable to other interpretations, such as, for instance, what might be considered aesthetic obsolescence.

In this model of the world and architecture’s place within it, however, the buildings remain unaltered; their obsolescence therefore is a result of something extrinsic, as it is with military aircraft. They both can be considered as obsolete through changes in the patterns of use which can no longer be accommodated. Whereas with the weapon, such changes can be decided with considerable exactitude, the dismissal of a building on similar grounds is more difficult to achieve. This is perhaps further evidence of the entwining of function and behaviour in Modernist thinking.

The residual idea of functionalism is probably that which envisages buildings as purposeful in achieving social progress, and consequently becoming obsolete once the stated purpose has been achieved: that is, prisons would be demolished once all criminals have been corrected through their use and mental hospitals closed once their inmates were returned to sanity.5

The function of buildings in human affairs is more correctly described through patterns or rituals of occupation. Buildings will otherwise resist description in terms of more precise functions; as James Gowan has sometimes commented to me, ‘I can eat a sandwich in any size of room’. The intended fit between function and space can be elusive, unfocused, but the image is vivid, which is a reason why the idea of obsolescence is so uncertain with regard to buildings.

The Modernist pursuit of the minimal dwelling was perhaps at root as much an attempt to avoid this difficulty in functionalist theory as it was a concern for cost. It is the alteration in the rituals of occupation that will cause a building to be considered obsolete.

The mutability of function may be more easily described by considering a specific typology, for instance a railway terminal such as King’s Cross Station6 in London, today and at its inception. The change from steam to diesel electric has been accommodated but not exploited, as for instance in not occupying the huge air volume previously required for the dispersal of coal smoke and steam. Unlike with military hardware, technological advances are perhaps less threatening to the existing built form than changes in the conduct of everyday life, because it is these that render the functional description of the building today at odds with its original form. A primary function of railway termini now, as with other transport interchanges such as airports, is the correct siting of retail units, which is the result or the cause of changes in our collective behaviour.

Peter Reyner Banham’s obituary for the Machine Aesthetic7 made similar comparisons in attacking it as an outmoded and misleading symbol of clarity and purpose. He most clearly recognized the delusion that the phrase form follows function could apply equally to machine and human behaviour, and that pure built forms would promote a desired way of life. However, I don’t believe that he entirely lost an allegiance to the notion; part of him remained an unreconstructed Modernist.8

Architecture operates in the world in similar ways to ideology, that is by being clearly conceived in the beginning by the authors, and more diffusely received by the populace.

The purest architecture appears always from seismic shifts in the human psyche. Buildings are too expensive for it ever to be otherwise. The purest buildings are set up to propagate a deep collective conviction. Architects are tempted to believe that the very quality of the architecture is proof or otherwise of the strength of those convictions. Nothing happens without self-interest. The priests at the Council of Trent must have been at least a little concerned about their future stipends when prescribing the architecture of the Counter-Reformation, but underlying all great epochs of building are deeply imbibed systems of belief. It is just this that gives architecture its tragic stature. Architecture sets out time and again to construct Utopia, and in so doing the accompanying act of widespread demolition may be legitimized as ridding the world of a heresy.

The architect has his own agenda, deeply intuitive in impulse and somehow in that strange human way detached at the point of insight from the very convictions to which he is required to give expression.

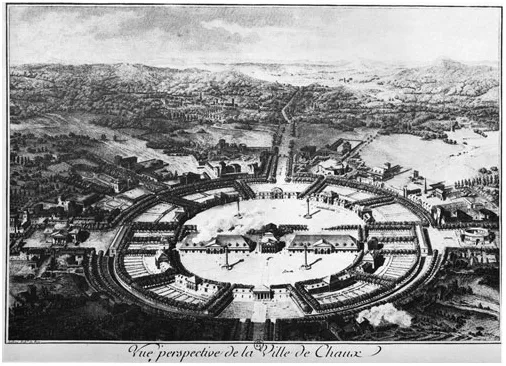

Katherine Shonfield9 has talked brilliantly of the basket domes of the Baroque churches in and around Turin as a response by Guarini and others to the admonitions of the Counter-Reformation to represent in built form a ‘faith beyond reason’. One might add that Vignola’s Jesuit church in Rome is the first great response to the new Catholic doctrine, and go on to trace the correspondence between architecture and eruptions of belief, to include of course the projects of Ledoux and Boullee for the Revolutionary society in France at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, Ledoux’s project for the Saltworks near Besançon that was intended as a matrix for the ideal community (Figure 1.2). In the last century, of course, Le Corbusier in writing Vers une Architecture (1923) and La Ville Radieuse (1935), created his own scriptural texts which were as much a call to a new way of life as they were a recipe for how buildings were to be made. From the work of such architects we derive our understanding of a building as a work of art.

1.2 Project for saltworks at Chaux near Besançon by Ledoux, 1773–79

The idea of a work of art is one that attempts to exclude alteration. In practice, this is generally undertaken through strict environmental control. Just as it seems strange sometimes that the universe is not just an infinite fizz of basic pa...