eBook - ePub

Risk Factors for Youth Suicide

Lucy Davidson, Markku Linnoila, Lucy Davidson, Markku Linnoila

This is a test

Share book

- 278 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Risk Factors for Youth Suicide

Lucy Davidson, Markku Linnoila, Lucy Davidson, Markku Linnoila

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Papers presented at the National Conference on Risk Factors for Youth Suicide, held at Bethesda in 1986. The authors catalogued, analyzed and synthesized the literature on factors linked to youth suicide.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Risk Factors for Youth Suicide an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Risk Factors for Youth Suicide by Lucy Davidson, Markku Linnoila, Lucy Davidson, Markku Linnoila in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

COMMISSIONED

PAPERS

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC, EPIDEMIOLOGIC, AND

INDIVIDUAL ATTRIBUTES

Paul C. Holinger, M.D., M.P.H., Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Rush-Presbyterian-St Luke's Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

Daniel Offer, M.D., Associate Professor of Psychiatry Rush-Presbyterian-St Luke's Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois

INTRODUCTION

From an individual, clinical point of view, it is difficult to overestimate the distressing, disastrous impact of the suicide of a young person. The impact on parents, siblings, friends, and the community seems almost inexpressible. However, the extent to which one views self-destructiveness among the young as an issue in the public health and epidemiologic realms seems dependent on the context and perspective. On the one hand, suicide is the second leading cause of death among 15 to 24 year olds in the United States (following only accidents) (National Center for Health Statistics, 1985) and, primarily because of the number of suicides, homicides, and accidents among young people, violent deaths* are the leading cause of number of years of life lost in this country (Holinger, 1980). On the other hand, young people have the lowest suicide rates of any age group and are at least risk of dying by suicide (Holinger, Holinger, and Sandlow, 1985).

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, we will present and evaluate the epidemiologic data related to suicide among adolescents. Second, we will discuss the potential for the prediction of youth suicide on an epidemiologic level. The focus will be on completed suicides, and we will utilize a developmental model emphasizing early (10–14 years old), middle (15–19 years old), and late (20–24 years old) adolescence, with an emphasis on the 15 to 19 and 20 to 24 year olds. The paper is divided into six sections; sections on literature, methodology, data, discussion, and future research will follow this brief introduction.

LITERATURE

This section on literature will focus on the epidemiology and potential prediction of adolescent suicide.

Of the many tasks of science, perhaps one of the most important is that of prediction, especially if such prediction can lead to effective intervention. Two types of studies over the past five years have begun to suggest that prediction of certain violent deaths may be possible for some age groups. One type of study involved the use of a population model (Holinger and Offer, 1983; Holinger and Offer, 1984; Holinger and Offer, 1986; Holinger, Offer, Ostrov, et al., unpublished data), and the second type of study utilizes cohort analysis (Solomon and Hellon, 1980; Hellon and Solomon, 1980; Murphy and Wetzel, 1980; Klerman, Lavori, Rice, et al., unpublished data).

In our 1981 examination of the increase in suicide rates among 15 to 19 year olds during the past two decades (Holinger and Offer, 1981), we reported that simultaneous with an increase in suicide rates was a steady increase in the population of 15 to 19 year olds from just over 11 million in 1956 to nearly 21 million in 1975. A subsequent study then related the changes in the adolescent population and changes in the proportion of adolescents in the total U.S. population to the adolescent suicide rates during the twentieth century in the United States (Holinger and Offer, 1982). Significant positive correlations were found between adolescent suicide rates, changes in the adolescent population, and changes in the proportion of adolescents in the population of the United States, i.e., as the numbers and proportion of adolescents increased or decreased, the adolescent suicide rates increased and decreased, respectively. It should be recalled that while one might assume that the number of deaths from a particular cause will increase with increases in the population, the mortality rates do not necessarily increase with an increase in population because the denominator is constant (i.e., deaths/100,000 population).

Cohort analyses have also provided data to demonstrate the increase in suicide rates among the young (Solomon and Hellon, 1980; Hellon and Solomon, 1980; Murphy and Wetzel, 1980; Klerman, et al., unpublished data). Solomon and Hellon (1980), studying Alberta, Canada, during the years 1951 to 1977, identified five-year age cohorts, and followed the suicide rates as the cohorts aged. Suicide rates increased directly with age, regardless of gender. Once a cohort entered the 15 to 19 year old age range with a high rate of suicide, the rate for that cohort remained consistently high as it aged. Murphy and Wetzel (1980) found the same phenomenon, in reduced magnitude, in larger birth cohorts in the United States. Not only does each successive birth cohort start with a higher suicide rate, but at each successive five-year interval it has a higher rate than the preceding cohort had at that age. Klerman, et al. (unpublished data), noted a similar cohort effect in their study of depressed patients.

There are both similarities and differences between the population-model and the cohort-effect studies. The similarities lie in the emphasis on recent increases in suicide rates among the younger age groups. The differences are in the predictive aspects. The cohort studies suggest that the suicide rates for the age groups under study would continue to increase as they are followed over time. Implicitly, the cohort studies also seem to suggest that the suicide rates for younger age groups will continue to increase as each new five-year adolescent age group comes into being. The predictions by the population model are different. The population model suggests that suicide rates for younger age groups will begin leveling off and decreasing, inasmuch as the population of younger people has started to decrease. In addition, the population model suggests that as the current group of youngsters gets older, suicide rates will increase less than the cohort studies would predict. It is well known that male suicide rates increase with age in the United States while female rates increase with age until about 65 and then decrease slightly (Kramer, et al., 1972; Holinger and Klemen, 1982). Therefore, one would expect an increase in suicide rates age consistent with this long-established pattern. However, the current group of adolescents and young adults make up an unusually large proportion of the U.S. population. The population model suggests that the larger the proportion of adults in the population, the lower will be their suicide rates. Thus, the population model would suggest that the suicide rates for the adult populations would decrease over the next several decades compared with adult rates in the past, consistent with the movement of the “baby boom” population increase through those adult age groups. This is not to say that the rates for the older groups of the future might be expected to have smaller suicide rates than the older groups of the past.

Other literature is also relevant to the issue of violent deaths, population shifts, and potential prediction. Positive relationships between population increases and upsurges in the rates of various forms of violent death are described by Wechsler (1961), Gordon and Gordon (1960), and Klebba (1975). These findings were not supported by the work of Levy and Herzog (1974, 1978), Herzog, et al. (1977), and Seiden (1984) in their reports of negative or insignificant correlations between both population density and crowding and suicide rates.

The work of Easterlin (1980) and Brenner (1971, 1979), with extensive research of population and economic variables, respectively, and other related studies (Seiden and Freitas, 1980; Peck and Litman, 1973; Klebba, 1975; Hendin, 1982) began to suggest the potential for prediction of suicide and other violent deaths. Turner, et al. (1981), showed that the birth rate increased with good economic conditions, and decreased with poor conditions. Previous studies specifically examined the potential of a population model to predict the patterns of violent deaths (Holinger and Offer, 1984). This model was also related to economic changes, with a suggested interaction of economic and population variables (e.g., good economic conditions leading to an increased birth rate with subsequent population changes) that helped explain violent death rates from an epidemiologic perspective.

Other Factors. Summaries of other risk factors for suicide among children and adolescents have been presented elsewhere (Holinger and Offer, 1981; Seiden, 1969), but brief mention should be made here of three other variables: geographies, divorce rate, and teenage pregnancy. With respect to geographies, the western States have the highest suicide rates among adolescents, and the eastern States tend to have lower rates (Seiden, 1984; Vital Statistics of the United States, 1979). The birth rates for teenagers and the divorce rate for all ages have increased recently, paralleling the recent in creases in suicide rates among the young, but these parallels were not consistent early in the century (Vital Statistics of the United States, 1979; Shapiro and Wynne, 1982).

METHODOLOGIC ISSUES

Methodologic Problems. Although we present elsewhere detailed discussions of the methodologic problems in using epidemiologic data to analyze violent deaths (Holinger and Offer, 1984; Holinger, in press, 1987), we will note the more important issues here.

Two major types of methodologic problems occur when using national mortality data to study violent death patterns: (1) under- and overreporting; and (2) data misclassification. Underreporting may result in reported suicide data being at least two or three times less than the real figures (Hendin, 1982; Seiden, 1969; Toolan, 1962, 1975; Kramer, et al., 1972). The underreporting may be intentional or unintentional. In intentional underreporting, the doctors, family, and friends may contribute to covering up a suicide for various reasons: guilt, social stigma, potential loss of insurance or pension benefits, fears of malpractice, and so on. Unintentional underreporting refers to deaths labeled “accidents,” e.g., single car crashes or some poisonings, which were actually suicides but were unverifiable as such because of the absence of a note or other evidence. Studies of violent deaths among youth involve additional methodologic problems. There may be greater social stigma and guilt surrounding suicide in childhood and adolescence because of the intense involvement of the parents at that age and the parents feeling that they have failed and will be labeled “bad parents.” In addition, it may be much easier to cover up suicide in the younger age groups. Poisonings and other methods of suicide are more easily perceived as accidents in those age groups than in older age groups.

Two types of data classification problems exist. One involves classification at the national level and the changes in this classification over time. The changes in Federal classification over time have been outlined in various government reports (Dunn and Shackley, 1944; Faust and Dolman, 1963a, 1963b, 1965; Klebba and Dolman, 1975; National Center for Health Statistics, 1980; Vital Statistics — Special Reports, 1941, 1956). There has been little change over the century in Federal classification for suicide. The second type of data classification problem concerns classification at the local level, e.g., the legal issue involving the requirement of some localities for a suicide note as evidence of suicide; this practice both decreases numbers and biases results because only the literate can be listed as having committed suicide.

Sources of Data. Sources of population and mortality data are noted in the respective tables and figures of this report. The data used from 1933 to the present are for the complete population, not samples: they in clude all U.S. suicides among the age groups indicated. With the exception of Figure 1, data prior to 1932 are not utilized in the present report as they are sample data and include only death registration States and areas utilized by the Federal government during any specific year. It was only after 1933 that all States were incorporated into the national mortality statistics (with Alaska added in 1959 and Hawaii in 1960).

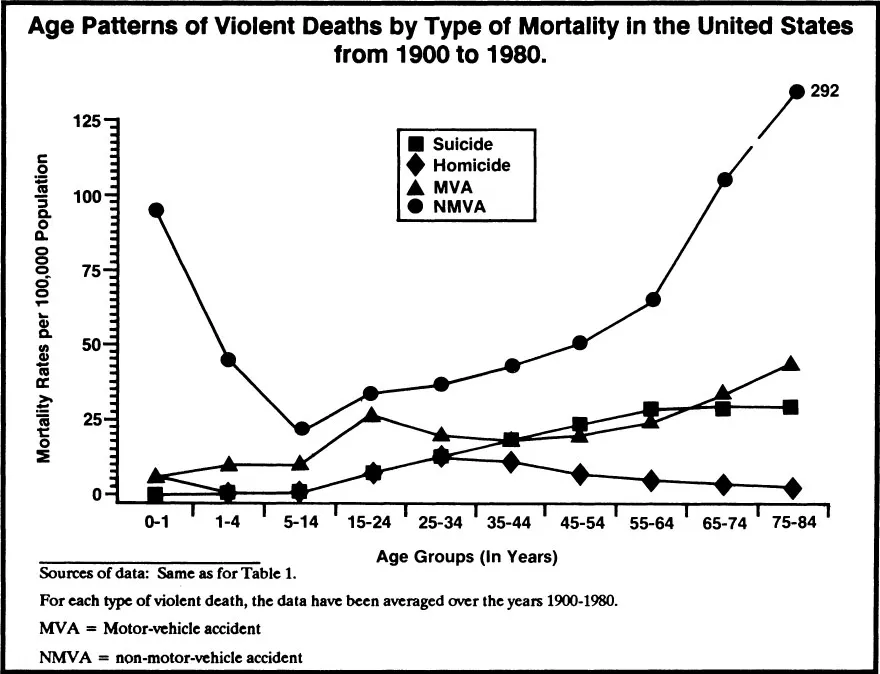

Other Forms of Violent Death. Suicide, homicide (homicide mortality rates refer to those killed, not the killers), and accidents have been studied in aggregate (Weiss, 1976; Holinger and Klemen, 1982), and have been related in that all may represent some expression of self-inflicted mortality (Wolfgang, 1959; Menninger, 1938; Freud, 1901; Farberow, 1979). Homicide and accidents may be self-inflicted in that some victims may provoke his or her own death by “being in the wrong place at the wrong time” (Tsuang,

Figure 1.

Boor, and Fleming, 1985; Wolfgang, 1959, 1968; Doege, 1978). Although suicide is the most overt form of self-inflicted violence, homicide and accidents can be more subtle manifestations of self-destructive tendencies and risk-taking (Holinger and Klemen, 1982). However, this paper focuses primarily on that most overt form of self-destructiveness: suicide.

Methodologic Issues in Studying Adolescent Suicide and Population Shifts. The general methodologic considerations were discussed above. The sources of population, suicide, and homicide data are noted in the respective tables and figures of this section. With respect to population data, both the figures and the correlations utilize the proportion of the population of a given age in the entire U.S. population (e.g., the proportion of 15 to 24 year olds in the entire U.S. population). Homicide data as well as suicide data will be noted, and the focus will be on 15 to 24 year olds. The correlations were derived as described previously (Holinger and Offer, 1984).

In addition to the possibility discussed below that there is a meaningful relationship between violent death rates and population shifts, one must also consider the possibility that either artifact or other variables are responsible for correlation. The possibility that the correlations are artifact because of change in Federal classifying of suicide and homicide is unlikely: as described above, the comparability ratios for suicide and homicide have been rather consistent over the decades. However, the possibility that another variable is involved, specifically period effects due to economic trends, needs to be addressed. In the early 1930's (the starting point of these data, when the entire U.S. population was included in the mortality figures), the mortality rates were at their peaks, probably because of the economic depression. The violent death rates decreased for several years following, reaching low points during the early 1940's (World War II).

During the time of this decrease in rates, however, the population of the adults (35 to 64 years) in the United States increased steadily. These economic shifts could then be seen to contribute to the inverse correlations, with the population variable having a coincidental, rather than etiologic, relationship with the violent death rates. The time trends of violent deaths in the United States (e.g., the tendency of violent death rates to increase in times of economic depression such as the early 1930's and decrease during war as in the early 1940's with World War II) have been presented in detail elsewhere (Holinger and Klemen, 1982).

DATA

Epidemiologic Data. Figure 1 presents age patterns of violent deaths by type of mortality in the United States, averaged over the ...