![]()

Part I

The theory of complexity

![]()

1 Complexity theory

An introduction to complexity theory

None of us can exist independent of our relationships with each other. ‘Complexity’ derives from the Latin root meaning ‘to entwine’; the notion that an organism interacts dynamically with its environment, influencing and, in turn, being influenced by its environment, is a key principle of the emerging science of complexity. The burgeoning interest shown in this field touches several areas of human life, for example anthropology, biology and ecology. Since the 1970s and 1980s there has been an alignment of complexity theory with business and management practices (e.g. McMaster, 1996; Conner, 1998; Kelly and Allison, 1999), postmodernism (e.g. Cilliers, 1998) and education (e.g. Morrison, 1998). Indeed Fullan (2001: 70) is unequivocal in his view that all schools, if they are to survive, must [his term] understand complexity science.

Consider this example: there is a ‘teaching’ headteacher of a small, four-teacher, rural village primary school in the UK which serves a remote, introverted area, where employment options for adults are largely either farming or nothing. The school enjoys good relationships with parents, but this does not extend beyond formal meetings and visits for ‘special events’. The headteacher is disenchanted with recent government reforms of education, as, he argues, they are removing him from those parts of his work for which he came into teaching – working with children, instructional leadership, professional autonomy and informed pedagogical freedom, teaching and a set of values for a liberal arts and humanistic tradition of education. Sensing that the situation of government prescription is unlikely to change he decides to take early retirement.

On taking up her new appointment, the new headteacher decides that the children need to be equipped to take their place in new employment markets, probably outside the neighbourhood. She feels that the horizons of the local population need to be extended, that the curriculum of the school needs to place greater emphasis on ICT, and that the school could become much more of a community resource. To that end she discusses with the teachers in the school and through a series of open meetings with the parents, ways of moving the school forward. This leads to the establishment of a range of ‘out-of-hours’ classes in IT for adults, the school becomes a centre for job advertising and for Internet links, and the three other teachers in the school together make concerted changes to pedagogy, so that large parts of the curriculum become learner-centred and ICT-driven. A small building programme takes place to convert rooms into a learner-resource suite, and parent-assistants come into the school on a regular, organized basis.

Within one year the school has changed from a slightly sleepy, if well-intentioned and friendly, place, into a vibrant community with links and connections to the outside community and beyond. In the school, teachers ‘share’ classes and work together far more closely, and involve parents in decision making on curricular and pedagogic matters – the school has moved from benevolent autocracy to participatory democracy. Children and parents have raised aspirations.

What has happened here? The school had reached a critical point where the former headteacher stayed or went (a ‘bifurcation point’ at the point of self-organized criticality in terms of complexity theory, discussed later in this chapter) – where events had built up until a new resolution had to be found by changing the school. The new headteacher sees that the school is ‘out-of-step’ with its environment; to bring the school into more developed relations and closer connectedness with its environment requires new networks with the environment to be made (external connectedness, see Chapters 5 and 7). For this to operate successfully requires internal changes to the school (internal connectedness, see Chapter 7). The headteacher’s leadership is facilitatory (see Chapter 3), fostering new connections and more developed relations both internally and externally, premised on extensive communication (see Chapter 6). The school has changed through self-organization (discussed in this chapter) with supportive leadership, and a new organization has emerged in the form of team-based teaching (see Chapter 2 and this chapter). Further, the school has become an open system and has impacted on its local environment – it has been affected by the local environment and, in turn, has affected that environment (see Chapter 5); all parties have learned through feedback (see Chapter 4). Complexity theory provides a useful way of explaining the events that took place.

Complexity theory is a theory of survival, evolution, development and adaptation.1 It has several antecedents, yet it breaks the bounds of these. Hodgson (2000) traces the roots of the concept of emergence to the nineteenth century philosopher Lewes, and the concept of unpredictability to the philosopher Morgan (1927: 112). In the 1930s, the New Zealand economist Souter and the English economist Hodgson discussed the significance of emergence and its unpredictability (Hodgson, 2000). More recently Hodgson cites the work of Polyani in the 1960s on the concept of emergence in the natural and social sciences. Lewin (1935, 1938, 1951) considered the behaviour of individuals and groups to be the interactions between personalities, individuals and their environments, each of which brings driving and restraining forces. He argued that systems are in constant flux rather than stability (De Smet, 1998: 7).

The foundation of Open Systems Theory, a forerunner of complexity, was formulated by Von Bertalanffy – a biologist – from the 1930s onwards (Von Bertalanffy, 1968) and was taken further into Open Systems Theory by Katz and Kahn (1966, 1978) who, themselves, built on the work of Allport (1954, 1962). Here an open system is dynamic, its members living and exerting agency, and its changes irreversible and self-regulating. Novel changes for an uncertain and unpredictable future emerge spontaneously through the interaction of the organism with its environment.

This is a holistic, connectionist and integrationist view of the individual and the environment, rather than a fragmented, reductionist perspective (Youngblood, 1997: 34). In this view feedback is essential for development and change, and interdependence of the organism and its environment are emphasized. The dynamic flavour of Open Systems Theory is particularly appropriate for the study of turbulent behaviour (Malhotra, 1999: 3), and here the individual and the environment change each other. Katz and Kahn (1978) suggest that open systems import, store and use energy and information from outside so that the system can adjust to its environment; indeed they suggest that systems have an innate propensity towards increasing in size and complexity (see also De Smet, 1998: 8). Complexity theory goes further than Open Systems Theory, for Open Systems Theory is ultimately teleologically deterministic and its consideration of nonlinear systems marginal, whereas complexity theory breaks with this (Stacey, 2000: 296; Stacey et al., 2000: 92).

Complexity theory is the offspring of chaos theory, but, as with Open Systems Theory, moves beyond it. Chaos theory, whilst stressing the unpredictability of the future, the system’s sensitivity to initial conditions (which can never be measured precisely, thereby giving rise to unpredictable futures) and the importance of examining nonlinear systems, is premised on the same rationalist teleological determinism as Open Systems Theory (Stacey, 2000: 296; Stacey et al., 2000: 142), as it uses the iterative, recursive process of making the outcome of one calculation the input to the next stage of the system (Gleick, 1987; Stacey, 2000: 322).

By contrast, complexity theory incorporates, indeed requires, unpredictable fluctuations and non-average behaviour in order to account for change, development and novelty through self-organization (discussed later). Chaos theory, Stacey suggests (ibid: 296; Stacey et al., 2000: 89–96), has little internal capacity for spontaneous change from one ‘strange attractor’ to another, whereas complexity theory incorporates, indeed requires, spontaneous reorganization emerging from the interaction of elements. Chaos theory, like other systems theories, Stacey et al. (2000: 90) aver, has little room for novelty or creativity; the model implied in the original specification simply unfolds over time. It is a model which cannot apply comfortably to human interaction as human action is not so deterministic (ibid: 91).

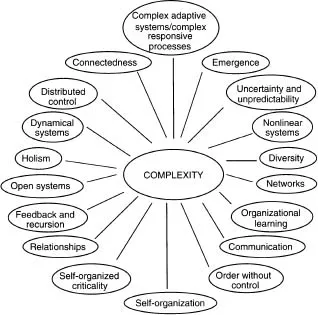

Complexity theory, as a complete theory, developed from the 1980s, particularly in the work of the Santa Fe Institute in the United States. In some senses the ancien regime of chaos theory has given way to the study of complexity as ‘life at the edge of chaos’. It is an attempt to explain how open systems operate, as seen through holistic spectacles. In complexity theory a system can be described as a collection of interacting parts which, together, function as a whole; it has boundaries and properties (Lucas, 2000: 3). This interaction is so intricate that it cannot be predicted by linear equations: there are so many variables involved that the behaviour of the system can only be understood as an ‘emerging consequence’ of the sum of the constituent elements (Levy, 1992: 7). The key elements of complexity theory are set out in this chapter (Figure 1.1).

Complexity theory looks at the world in ways which break with simple cause-and-effect models, linear predictability and a dissection approach to understanding phenomena, replacing them with organic, nonlinear and holistic approaches (Santonus, 1998: 3) in which relations within interconnected networks are the order of the day (Youngblood, 1997: 27; Wheatley, 1999: 10).

In the physical sciences, Laplacian and Newtonian theories of a deterministic universe have collapsed and have been replaced by theories of chaos and complexity in explaining natural processes and phenomena, the impact of which is being felt in the social sciences (e.g. McPherson, 1995). For Laplace and Newton, the universe was a rationalistic, deterministic and clockwork order; effects were functions of causes, small causes (minimal initial conditions) produced small effects (minimal and predictable) and large causes (multiple initial conditions) produced large (multiple) effects. Predictability, causality, patterning, universality and ‘grand’ overarching theories, linearity, continuity, stability, objectivity – all contributed to the view of the universe as an ordered and internally harmonistic mechanism in an albeit complex equilibrium; a rational, closed and deterministic system susceptible to comparatively straightforward scientific discoveries and laws. The differences between conventional wisdom and the principles of complexity theory are set out in Table 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Components of complexity theory.

Table 1.1 Conventional wisdom and complexity theory

| Conventional wisdom | Complexity theory |

| Small changes produce small effects | Small changes can produce huge effects |

| Effects are straightforward functions of causes | Effects are not straightforward functions of causes |

| Similar initial conditions produce similar outcomes | Similar initial conditions produce dissimilar outcomes |

| Certainty and closure are possible | Uncertainty and openness prevail |

| The universe is regular, uniform, controllable and predictable | The universe is irregular, diverse, uncontrollable and unpredictable |

| Systems are deterministic, linear and stable | Systems are indeterministic, nonlinear and unstable |

| Systems are fixed and finite | Systems evolve, emerge and are infinite |

| Universal, all-encompassing theories can account for phenomena | Local, situationally specific theories account for phenomena |

| A system can be understood by analyzing its component elements (fragmentation and atomization) | A system can only be understood holistically, by examining its... |