eBook - ePub

Drinking Occasions

Comparative Perspectives on Alcohol and Culture

Dwight B. Heath

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Drinking Occasions

Comparative Perspectives on Alcohol and Culture

Dwight B. Heath

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The main purpose of this book is to describe the variety of drinking occasions that exist around the world, primarily in modern, industrialized countries. As such, it celebrates the diversity of normal drinking behavior and illustrates a wide range of beneficial drinking patterns. Attention is also paid to the relations between drink and culture that prevail in non-Western societies and in developing countries. The aims of the book are twofold: to deal directly with the challenge of how to define responsible drinking in the face of the world's many different drinking styles, and to portray the many ways in which people have thought about or used alcohol as an integral part of their culture

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Drinking Occasions an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Drinking Occasions by Dwight B. Heath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Storia e teoria della psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

To Every Thing There is a Season: When Do People Drink?

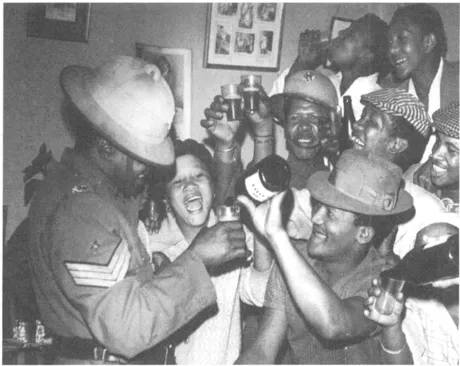

South Africans, including a uniformed policeman, enthusiastically mark the legalization of alcohol in a shebeen (neighborhood bar). Even the repeal of a law can be an occasion for celebratory drinking, particularly among its detractors. © Alf Kulalo.

At the same time that few kinds of behavior are more natural and necessary than drinking, there are also few kinds of behavior that are more hedged about by rules, laws, and understandings about when it’s to be done or not to be done. Such conventions are clearly social, inasmuch as we find that they vary from one group to another, and they can change, sometimes rapidly and drastically, within a single group. They are also emotionally laden, as reflected in the ways that people feel about them, the intense degree of rancor that can be meted out for a breach of propriety, or the outpouring of warm support that often accompanies the act when it is done in what is locally “the right way,” and at a time that is appropriate in terms of the prevailing social code. A brief sampling of the different ways that beliefs about when one may drink will reveal the wide range of variation in that, and also in beliefs about when one should, or even must drink. Similarly, the negative rules—about when one must not drink or should not, or even may not, have affective importance with reference to drinking far beyond what we find with respect to most other behaviors.

Quantitatively oriented epidemiological surveys are the kind of research on drinking that is most often cited when practical or theoretical implications of drinking are being considered. These include matters such as rates of drinking, rates of problems, and risk factors. Often the data are collected in terms of the amounts that respondents drank “the last time they drank,” “on a typical day,” or “on the last drinking occasion,” and they tend to be reported as “per drinking occasion.” For that reason, the drinking occasion would appear to be a crucial variable in our understandings about how people relate to drinking and how drinking relates to people. Unfortunately, although those who devise and conduct such surveys may each have a clear idea of what is meant by the term “drinking occasion,” few respondents do. To make matters worse, the data that are collected with reference to an entire day are often analyzed and interpreted as if they relate to a single drinking occasion. This results in a significant scientific error, as well as significant amplification of whatever problems are said to be related to alcohol (Room, 1991a and c; 1997).

An open-ended, qualitatively oriented survey recently conducted by the author in several countries indicates an obvious disjuncture between the ways in which most people understand the questions to which they respond, and the theoretical and practical uses to which their responses are later put by the investigators. A qualitatively oriented researcher who is more concerned with meaning and context than with numbers, is apt to find out from the actors themselves when they drink. The responses that they provide give clues as to how they conceptualize time as well as how they view drinking. Our case study in this chapter deals with how contemporary, urban Spaniards talk about the times when they drink. It is remarkable that so many of them indicate drinking occasions that are important to them throughout the entire 24 hours of a day. The rest of the chapter includes a sampling of illustrative material from different cultures around the world with respect to when people drink—or not. There are, of course, different kinds of times that have to be considered. One kind has to do with when, in terms of calendrical chronology: at what time in the day, what day of the week or month, what season or special event, and so forth. Another type of time has to do with when, in terms of people’s lives: at what specific age, at what stage in the developmental cycle of the household or family, in relation to age-grades, marital status, parenthood, work, and so forth. A third type of time with which we deal relates to when, in history: long evolutionary cycles within a culture, movements of people and linkages between cultures, war and peace, natural disasters. And, of course, there are numerous occasions in which people drink that fit none of those categories. Our aim is not to be encyclopedic, but to highlight the variability within the human experience as regards this fundamental question about drinking occasions, before we go on to examine other important variables.

Case Study: Spanish Drinking Around the Clock

“In Spain, alcoholic beverages are woven into the cultural fabric of everyday life” (Gamella, 1995). They have always been the major social lubricant and a source of conviviality and sociability. Although social drinking peaks on festival days, such as Corpus Christi, pre-Lenten Carnaval, and the local fiestas that mark the anniversary of the patron(ess) of every local community or institution, private rites are also marked by drinking, such as birthdays, Catholic confirmation, 15th-year celebrations marking a girl’s coming of age, marriage, and even death and burial. A meal is often considered to be incomplete without wine, which is thought to sharpen the mind, uplift the spirit, strengthen the body, and generally enhance one’s health and well-being. Wine is generally available at any grocery store as well as at many gas stations and open markets. Although most people drink each day, drunkenness is generally discouraged and looked down upon as a sign of weakness in a country where men take great pride in their masculinity. In recent years, wine has been losing ground to beer as favored drink, with women and young people accounting for much of that change.

The temporal dimension is important, and drinking that is acceptable at one time may not be at another, even in the same social situation. In hot weather, thirst-quenchers like cold beer, sangria, or diluted wine are popular, whereas straight whiskey, sherry, brandy, or wine are preferred when it is cold. Weekends and holidays tend to be more leisurely for most people, and so entail more drinking. Any fiesta, sacred or secular, is marked by more than usual drinking and a few specific occasions, different in different communities, may involve more than usual drinking by most people. It is important in Spain that one “know how to drink” and not exceed the level of becoming alegre (happy, or high, but without impairment).

The combining of food with drink is important, having resulted in the distinctive national tradition of tapas, bite-sized sandwiches or morsels, the quality and variety of which can bring notoriety to a bar. The daily schedule of social life tends to start earlier and to end later than in many other parts of Europe or the rest of the world. The daily round can be conceived as comprising eight distinct periods in relation to food and drink. Although few Spaniards drink during more than half of them, each such period provides a context in which some may drink without prompting comment from those who do not. According to Gamella (1995), metropolitan Spanish drinking routines literally occur around the clock. Breakfast time (7–10 a.m.) may well include one or more glasses of distilled spirits (aguardiente, anisette, or brandy) to energize a laborer, especially in winter. Morning (10–1 p.m.) brings a more substantial breakfast for many, with wine or beer as an accompaniment. Aperitif time (1–2 p.m.) is an occasion for relaxing conversation and socializing with friends and colleagues, often with a beer, liqueur, or glass of wine and a snack before luncheon. Lunchtime (2–3:30 p.m.) often includes the major meal of the day. Traditionally, most of the family may be at home for a lunch that includes at least three courses, accompanied by wine. This is also the time when the day’s main newscasts are aired on radio and television. Siesta time (3:30–6 p.m.) may begin with strong coffee and liquor after lunch, followed by a nap or rest. Evening (6–9 p.m.) is a favorite time for drinking, often combined with snacking on tapas. Especially among the young, barhopping at this time entails moving with a group of friends from one bar to another, with social interaction at a premium. Dinnertime (9–11 p.m.) often replicates the pattern of lunchtime, with less food and formality unless people eat away from home, in which event it may be even more elaborate. Night (11 p.m.–7 a.m.) is especially favored by young people as a time away from home, when relaxation, recreation, social and sexual encounters combine with drinking as a focal activity; drunkenness in such a context may be seen as a gesture of independence or a demonstration of wealth.

It would be a mistake to view this sequence as portraying a typical day in the life of an average Spaniard. The important point to be grasped is the acceptability of drink, usually with food, at almost anytime for someone, a degree of accommodation to beverage alcohol that is rare in other parts of the world.

THE CALENDRICAL ROUND

In many societies, a fermented homebrew is a basic staple in the diet and, as such, it is drunk as breakfast and as a refreshing break at almost anytime throughout the day. For the Tonga of Zambia, beer is not so much a complement or supplement to a meal as it is often a meal in itself (Colson & Scudder, 1988). The same can be said of many other populations throughout sub-Saharan Africa (Haworth & Acuda, 1998) or Latin America (Madrigal, 1998).

During a Day

An early morning drink may serve to provide the quick feeling of warmth or to invigorate or waken a worker. Slivovitz (plum brandy) is widely used for this throughout the Balkans, just as brandy or red wine is popular with French truck drivers, farmers, postal workers, shopkeepers, herders, and others whose workday begins earlier than that of most urban white-collar employees.

The familiar pattern of three meals daily, beginning with a morning breakfast, is an alien idea to many, so the rhythms of eating, drinking, and living, are very different around the world. Those who do drink alcohol with or as breakfast tend to do so with fermented homebrews but not with distilled or fortified beverages.

Despite the general rule in North America about not drinking in the morning hours, a few special exceptions have become institutionalized and accepted in recent years. The phenomenon of brunch, a meal later and larger than the usual breakfast and often served in buffet style, may include spirits mixed with orange or tomato juice, or champagne in the scrambled eggs. Code words to disguise such alcohol (Grasshopper, Bloody Mary) insulate people from having to articulate the fact that they are taking alcohol at what would, normally, for them be an inappropriate time. All involved are doubtless aware that some of the food in such a situation is actually ethanol.

In much of the urban industrialized Western world, midday is a significant boundary marker between drinking being inappropriate or permissible. People with higher schooling and larger incomes often routinely have one or more drinks with their noonday meal. In the late 1970s, U.S. President Carter derided “the 3-martini lunch” as emblematic of the hedonistic excesses of newly wealthy and powerful entrepreneurs. There are, however, individuals in finance, journalism, publishing, theater, and other white-collar occupations who consider drinking an integral part of a working lunch, during which considerable constructive talking and dealing often takes place, whether in the U.S. or anywhere else that they may meet with cosmopolitan colleagues.

The traditionally substantial midday meal in Spain (Gamella, 1995), France (Nahoum-Grappe, 1995; Sadoun, Lolli, & Silverman, 1965; de Certau, Giard, & Mayol, 1998), Italy (Cottino, 1995; Lolli, Serriani, Golder, & Luzzatto-Fegiz, 1958; Osservatorio, etc., 1998), and other northern Mediterranean countries, included significant quantities of drink, often a liter or more of wine per person. In recent years, both meals and drink are diminishing in many areas, as the pace of life appears to have accelerated. Workers who are on tight schedules, or remote from comfortable places to eat and drink, are less likely to make much of the midday meal as a context for drinking.

Although many North Americans and northern Europeans hold strongly to the view that drinking in the morning is morally wrong and a signal that the drinker is a drunkard, addicted, or will soon have problems, such drinking is acceptable in Chile, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, and in cultures where the drink is viewed as food, or at least as an important part of the diet (Heath, 1995). In general, it is more common for men than women. In many regions of southern Europe, elderly men who are no longer working daily spend large blocks of time in public drinking places, sipping slowly while talking, playing games, or simply enjoying the sun. Austrian housewives, also, sometimes drink small quantities of distilled spirits from time to time throughout the day, when they share a break in their work routine (Thornton, 1987).

It is acceptable to drink lightly with luncheon and or dinner in Australia or Canada, just as it is expected that one do so in the circum-Mediterranean countries. In Chile, China, Spain, or the Azores, it would be normal to offer a drink as a gesture of hospitality at whatever hour a guest arrived. Australians might do so after 2 p.m., or North Americans after 4 p.m. (Heath, 1995).

Although it is generally permissible to drink throughout the rest of the day in most societies, work often takes precedence, and there is a widespread reluctance to combine work with drinking. Certainly, that was not the pattern before the Industrial Revolution, when much of people’s work was in their home or someone else’s. Since then the risks of accidental injury or of damaging machinery have made it increasingly important to be at peak performance on the job (Fillmore, 1984). No matter what hours that one spends as an employee, it is generally agreed that one shouldn’t drink on the job—with some colorful exceptions, such as gamblers, prostitutes, and a few others. It used to be a standard perquisite that brewery workers had free access to a tap of their product, but questions of liability, insurance, and general health have resulted in that having virtually disappeared as an informal tradition.

Interestingly, in the course of doing a general ethnography of an automobile assembly plant in the U.S., an exception was found in that the workplace itself fostered a “drinking subculture,” with chronic boredom, lax supervision, easy concealment, and a feeling that to do so was a manly way to defy the management, who were resented for their lives of relative wealth and ease (Ames & Janes, 1987).

Craftsmen, railroaders, sailors, journalists, and early factory workers have all been noted as heavy drinkers in the U.S., both on and off the job (Fillmore, 1990). In a study of sandhogs (tunnel workers) in the U.S., Sonnenstuhl (1996) shows how that occupational group used to build their sense of community around intemperate drinking rituals that created solidarity. Remarkably, and within a single generation, they have transformed to having a temperate subculture in which their group identification is now divorced from heavy drinking.

It is commonplace that a drink or more can serve as a significant marker, symbolizing the shift from work to nonwork or leisure life. Among the Iteso of Kenya (Karp, 1970), this transition may comprise virtually all of the adult males gathering around a large pot of beer, drinking through elaborately decorated straws that each has made, and quietly talking about the cattle they have been herding all day. This takes place in different living-compounds on successive days, after they have penned their herds for the night and before they go to eat dinner at home.

Gusfield (1987) described a similar transition rite on the part of individuals in the U.S., many of whom come directly home from work and immediately have a drink, effectively signaling the change of pace and expectations. Others do not even bother to go home before dramatizing the end of the workday. Some bars advertise “happy hour” or “attitude adjustment hour,” with specially discounted prices on drinks for a couple of hours in the late afternoon or early evening.

It is only gradually becoming less common in the U.S. or Australia for factory workers, painting or construction crews, and others who have a sense of camaraderie to go to a nearby bar or tavern after work and to drink for an hour or more. Such behavior clearly marks a psychological boundary for them between work or the job on one hand, and leisure or off-the-job on the other. Where the local custom is to buy rounds, or shouting, with each member of the group buying drinks (usually beer) for all by turns, this may consume considerable amounts of time and money, and may result in the drinking of considerable quantities by each person. A shrewd bartender may encourage his clientele to stay longer by occasionally offering a free drink to everyone, proclaiming “This round is on the house,” and knowing that, the longer people stay, the more they will drink (Single & Storm, 1985). Some establishments also provide the convenience of cashing checks, so that one need not rush to the bank on payday; there is the implied expectation that some of the money will be spent there. Talking, horseplay (teasing), playing pool, cards, dice, or dominoes, watching television, listening to recorded music, or any combination of those often adds to the sociability of such an occasion.

Halfway around the world, there is a popular custom that is quite analogous in terms of the functions that it serves, but very different in its formal appearance (Sargent, 1967). Japanese office workers often similarly go out to drink together after work, but their behavior tends to be far more focused. Much of the conversation deals with the day’s work, and it is an occasion in which subordinates, who have quietly done as they were told all day, have an opportunity to express their feelings to supervisors. It is not only accepted but even appropriate for a Japanese male to act as if he were slightly drunk after a single drink, and to be voluble and heated after a couple of drinks (usually of sake, beer, or whiskey). In this context, it is expected that any grievances that may have arisen during the day will be aired without reservation, and that no one will take offense at what is said. In fact, the unspoken rule is that what transpires in those afterwork parties is to be forgotten, because no offense was intended and everyone was talking or acting under the influence of alcohol. With such an institutionalized understanding, informal communication may well be more effective than more formal exchanges between the same individuals. An insightful social critic has suggested that a U.S. housewife may justifiably worry that her husband is too social if he comes home late from the office, smelling of drink, whereas her Japanese counterpart may have equal reason for concern if her husband is so antisocial that he comes home early and does not smell of drink.

Blue-collar Hawaiians also tend to enjoy a designated period of time out after work and before returning home. Coworkers eat and drink together, but there is not the airing of grievances that plays so large a role among Japanese office workers.

The cocktail hour, at about the same time, serves much the same function in the lives of some who specifically prefer mixed drinks, or who emphasize socializing as much as drinking (Lolli, 1963). While on a boat, the convention is not to drink before “the sun is below the yard-arm” (i.e., almost sunset), but certainly to have one (or more) then.

Some jurisdictions specify hours before or after which public sales outlets may not serve drinks. In the early 1900s, Australian bars were required to close at 6 p.m., and there was often a ...